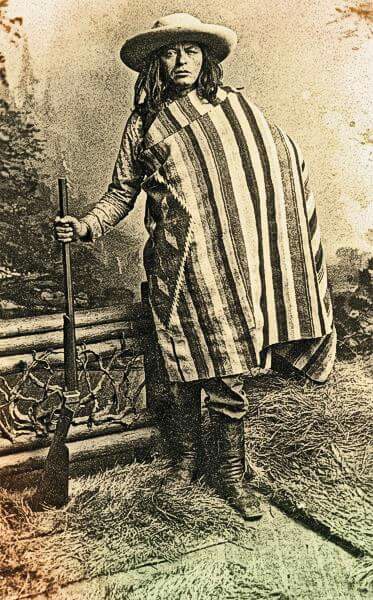

Wherever Mickey Free went, death seemed to follow. Even when he was a kid.

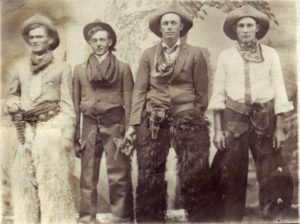

Wherever Mickey Free went, death seemed to follow. Even when he was a kid. Mickey Free – “Half Mexican, Half Irish and Whole SOB”

Wherever Mickey Free went, death seemed to follow. Even when he was a kid.

Wherever Mickey Free went, death seemed to follow. Even when he was a kid.

Wherever Mickey Free went, death seemed to follow. Even when he was a kid.

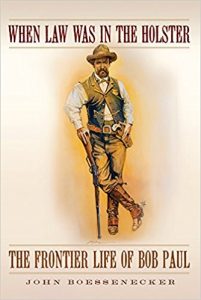

Wherever Mickey Free went, death seemed to follow. Even when he was a kid.  When Law Was In The Holster – The Frontier Life of Bob Paul, John Boessenecker, University of Oklahoma Press, (1-800-627-7377) $34.95, Hardcover.464 pages, Illustrations, Maps, Footnotes, Bibliography, Index.

When Law Was In The Holster – The Frontier Life of Bob Paul, John Boessenecker, University of Oklahoma Press, (1-800-627-7377) $34.95, Hardcover.464 pages, Illustrations, Maps, Footnotes, Bibliography, Index.

This is the biography of Sheriff Bob Paul, a frontier lawman in Old Arizona. He is remembered mostly as the shotgun messenger riding the Tombstone stage that was ambushed one night in March, 1881. The driver, Bud Phitpott was killed during a volley of gunshots fired by the robbers hidden beside the road. Philpott’s body hurled over the side of the coach while the driving lines slipped away and the terrified horses bolted. Bob Paul worked the brake for nearly a mile until he finally got the runaway team under control.

This stage holdup had to do with Tombstone history and has been told many times in connection with the days of Doc Holliday and the Earps. However, Bob Paul was far more important as a lawman, and his history is filled with excitement and derring-do that more than matched the Earps who dabbled periodically in law enforcement while Bob Paul spent nearly 50 years behind a badge.

Paul was born on June 12, 1830 in Lowell, Massachusetts. The youngest of three brothers, Paul spent his first few years in Lowell before the family moved to the seaport town of New Bedford. Here, they worked hard in their boardinghouse.

Paul’s father died in 1839, leaving the family in dire financial straits. Young Bob, only 12 years old, signed on as a cabin boy with the 197-ton whale ship Majestic.

Thus began a succession of experiences on a variety of whale ships for the next 8 years. Bob Paul advanced from cabin boy to second or third mate, sailing the South Pacific from Peru to the Sea of Japan and back to Hawaii.

In 1848, Paul learned of the huge gold strike in California, and seething with gold fever, asked for a discharge from the whale ship Nassau. He sailed right away for San Francisco. In time his prospecting led to law enforcement, as he learned the vagaries of the gold mining business did not always lead to economic security. Paul, a straight-shooter who stood over six feet tall, with massive frame and lighting fists, had a no-nonsense demeanor. In the rough and tumble goldfields, he arrested claim jumpers, rescued a number of individuals from vigilante justice, and himself oversaw legal hangings when he became sheriff of Calaveras County.

The book discusses his marriage to a young Catholic woman, followed by his employment as a Wells Fargo detective. Eventually the Paul family, having added a number of children, moved from California to Pima County, Arizona where Margaret lived with the children in Tucson.

In Cochise County Paul dealt with Tombstone politics, the rustler element, and a succession of notorious outlaws. He supervised the execution of the murderers who perpetrated the “Bisbee Massacre”, and eventually ran for Pima County Sheriff. For the rest of his life he dealt with political enemies, newspaper critics, and family tragedies. Sheriff Paul is the man who arrested and held the infamous lady stagecoach robber Pearl Hart in his Tucson jail.

Sheriff Bob ‘Paul is not a romantic figure wearing a long black coat, or having a squadron of brothers who looked just like him. The one woman in his life was his beloved wife from whom he never strayed. Hollywood did not single him out to star in romanticized flicks, but Sheriff Bob Paul was the real deal, and deserves to be finally recognized. This fascinating story so well written and carefully researched is certainly an important addition to your Old West library. Kudos to author John Boessenecker for a job well done.

Editor’s Note: The reviewer, Phyllis Morreale-de la Garza is the author of 15 published books about the Old West, including Nine Days at Dragoon Springs, published by Silk Label Books, P. 0. Box 700, Unionville, New York 10988-0700 www.silklabelbooks.com.

*Courtesy of Chronicle of the Old West newspaper, for more click HERE.

February 10, 1887, Daily Star, Tucson, Arizona Territory – The steady progress of Tucson in the direction of “culchah” and civilization, awakens the liveliest hopes of the future. As evidence that we are on the right road at last, we append the following rules of deportment posted in the office of a popular old resident of this country:

February 10, 1887, Daily Star, Tucson, Arizona Territory – The steady progress of Tucson in the direction of “culchah” and civilization, awakens the liveliest hopes of the future. As evidence that we are on the right road at last, we append the following rules of deportment posted in the office of a popular old resident of this country:

1 – Gentlemen entering this office will leave the door wide open, keep their hats on, and walk with the right hand carelessly foundling the handle of their six-shooters.

2 – Those having no business should remain as long as possible, take a chair and lean against the wall, and may prevent its falling on us.

3 – Gentlemen are required to smoke, especially during office hours; tobacco will be supplied.

4 – Spit on the floor, as the spittoons are only for ornament.

5 – Talk loud or whistle, especially when we are engaged. If this does not have the desired, effect, sing! And if that will not answer, then dance, or tell some old story; long ones preferred.

6 – Put your feet on the tables, or lean against the desk; it will be of great assistance to those writing on them.

7 – As an office is exclusively for your accommodation, call frequently when you have leisure – especially when we are busy; then ‘tis very pleasant.

8 – In making your visits, never come alone – the old adage – “the more the merrier.” Ride your broncos right into the office. It will make a good laugh all round. So Long.

Next to his hat, a cowboy’s footwear has traditionally been the most important symbol of his identity. Here are some little known facts about Old West Cowboy Boots:

Next to his hat, a cowboy’s footwear has traditionally been the most important symbol of his identity. Here are some little known facts about Old West Cowboy Boots:

Prior to the end of the Civil War, cowboys wore heavy-soled boots of virtually any style they could find. Often his boots were made on the same form for both the right and left foot. Although they eventually conformed to the foot, this wasn’t the most comfortable way to make a boot.

With the beginning of the cattle drives, and the cowboy having to work cattle and ride a horse for months at a time, he started realizing he wasn’t wearing the best boot for the job. So, when he got to Abilene and the other cattle towns, the cowboy got together with boot makers and came up with what has come to be known as the cowboy boot.

Early boots were called “stovepipes” because they were black, about fourteen inches tall and had level tops. The 1870’s cowboy had three choices: boots off the shelf, boots made by a local boot maker or custom made mail order boots.

The Old West cowboy was very vain about his attire. He was willing to pay as much as a month’s wages for a pair of custom boots that were designed more for looks than comfort.

Although the northern cowboy and the southern cowboy dressed differently, they did agree on their boots. The exception was how the boot was decorated. The Texas cowboy wanted a lone star or crescent on the front of his. The northern cowboy’s boots were heavily stitched. And their tops were rarely less than seventeen inches high.

Boots had square or rounded toes. (Pointed toes are a modern design.) The soles were thin. Supposedly, to better feel the stirrup. Besides, a cowboy never walked very far. The heels were “underslung.” A small foot was desired, and the underslung heel provided a size ten foot with a size seven footprint.

The heels were 2 ½ inch to as much as 4 ½ inch high. This prevented the boot from hanging up in the stirrup. In addition, the heels made it possible to “dig in” when working cattle. The tall heel also added a couple of inches to the height of a cowboy, who tended to be on the shorter side.

In the 1890’s, following the cattle drive era, performers in Wild West shows started wearing highly decorated boots. Then came the movie cowboy. Boots were no longer designed for protection against the elements and critters, or for riding and handling cattle, but for show and tell. And to tell it best, they always added a pair of jingling spurs! You can read more about cowboy boots in the Old West by grabbing this great book HERE.

Time in the United States, by law, is divided into nine standard time zones covering the states and its possessions, with most of the United States observing daylight saving time (DST) for approximately the spring, summer, and fall months. Time Zones in the United States is not new, and Dakota Livesay explains how the US got Time Zones.

Time in the United States, by law, is divided into nine standard time zones covering the states and its possessions, with most of the United States observing daylight saving time (DST) for approximately the spring, summer, and fall months. Time Zones in the United States is not new, and Dakota Livesay explains how the US got Time Zones.