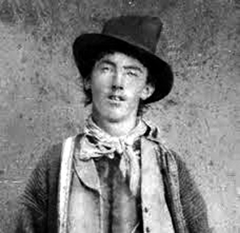

BILLY THE KID CONVICTED

Early in 1880, Sheriff Pat Garrett deposited Billy the Kid in jail, and left town thinking this would be the last he would ever see of “the Kid”. But it wasn’t so. Here is the story of what happened.

Early in 1880, Sheriff Pat Garrett deposited Billy the Kid in jail, and left town thinking this would be the last he would ever see of “the Kid”. But it wasn’t so. Here is the story of what happened.

Pat Garrett was elected sheriff on the promise that he would bring in Billy the Kid. And within a couple of months after being elected, he made good on his promise. Feeling that chapter closed, Pat Garrett left to find other outlaws.

Billy the Kid was transferred to the town of Messilla, New Mexico for trial. Having a number of possible charges to place against him, they settled on the killing Lincoln County Sheriff William Brady three years earlier.

Billy the Kid was convicted of murdering Sheriff Brady. In pronouncing the sentence, Judge Bristol said, “You are sentenced to be hanged by the neck until you are dead, dead, dead.” Billy the Kid comely responded, “And you can go to…” three times. The hanging was set for May.

Billy the Kid was sent back to Lincoln, New Mexico. Lincoln didn’t have a formal jail so he was shackled, locked in a room on the second floor of the courthouse and placed under a twenty-four hour guard.

On April 28, 1881 Billy received a note with one word on it…“Privy”. Understanding the meaning, Billy said he had to go to the outhouse. Hidden in the outhouse was a pistol. As Billy the Kid was returning to his room, he pulled the pistol and shot his escort. Next he broke into the armory, and got a shotgun. From a second floor window he yelled down to Robert Olinger, a guard that had been ragging on him. When Robert looked up, he was sent to eternity by a blast from his own shotgun.

An hour later, with shackles still hanging from one leg, Billy the Kid rode out of town, once again escaping death.

STAGE HOLD-UP

On March 15, 1881 the Benson-Tombstone stage was held up. Although not intended as such, it ended up being one of the causes for the O. K. Corral shootout. On the other hand, the two objectives of the hold-up were not accomplished.

The main objective was the assassination of Wells Fargo shotgun guard, Bob Paul. As a Wells Fargo guard, Bob Paul had hampered the activities of the cowboys. And, the word around town was that he was to become the Pima County Sheriff. So the cowboys wanted to get rid of him. The assassination failed because when the stage departed Tombstone, stage driver Budd Philpot had gotten stomach pains and Budd exchanged positions with Paul. Orders were to kill the guard…which they did, but it was Philpot instead of Paul.

Paul was also responsible for the robbers not accomplishing their second objective…the theft of $26,000 in silver. When Philpot was shot, Bob grabbed his shotgun and fired off both barrels. One robber was killed and the noise of the shotgun spooked the horses. As the stagecoach was careening out of control, Paul climbed down; secured the reigns of the runaway steeds; and brought the stage safely into Benson.

Later, when he did became the Pima County Sheriff this 6’ 6”, 240-pound mountain of a man, typically using a shotgun, brought in bad guys, stopped lynchings, and hanged many a man legally. It always seemed that he was able to dodge that fatal bullet…That is until 1893 when he couldn’t dodge the one called cancer, and he died on March 26, 1901.

UNDERDOGS

![]() When it comes to public opinion, quite often being the underdog and particularly a persecuted underdog gets everyone’s sympathy.

When it comes to public opinion, quite often being the underdog and particularly a persecuted underdog gets everyone’s sympathy.

In 1874, Jesse and Frank James were robbing banks and trains to the point that the railroads decided to hire the famous detective group the Pinkertons to hunt them down. But, the Pinkertons, in spite of their numbers and skill, weren’t having any luck rounding up the James boys. Then late in 1874 one of their agents, John Wicher was found dead close to the James home. The Pinkertons were convinced that the James’ or one of their people had killed him, and they decided to raise the ante.

Receiving information that Jesse and Frank were visiting their mother in Kearney, Missouri, on January 26, 1875, the Pinkertons surrounded the James home with the idea of catching Jesse and Frank. In the process, they threw an incendiary device into the house to illuminate the interior. But it exploded. Unfortunately, it blew off the arm of Jesse and Frank’s mother and killed their little brother. In addition to this, neither Jesse nor Frank was there.

Although the Pinkerstons never acknowledged that they were responsible for the bombing, everyone knew they did it. Realizing they had overplayed their hand, from this point forward the Pinkertons developed a low profile in their search for the James Brothers.

The bombing convinced everyone that the James Brothers were innocent victims of the powerful railroads. The Missouri legislature even came close to passing a bill that would give amnesty to the Jameses. And Zerelda Samuel, their mother, was always willing to make public appearances, showing her missing arm, and giving a melodramatic speech about how the evil railroads were persecuting her innocent sons.

It worked too. Because farmers throughout the region hid and protected the James Brothers, so the Pinkertons were never able to come close to catching them.

ELFEGO BACA

The subject of this story had more grit that the most famous heroes of the Old West. But chances are you’ve never heard of him.

The subject of this story had more grit that the most famous heroes of the Old West. But chances are you’ve never heard of him.

Although the Mexican people had traditionally occupied the southwest, by the 1880’s it comprised primarily of Angelo cattle ranches and towns…some, of whom, considered the Mexicans second-class citizens. A ranch owned by John B. Slaughter occupied the area around what is now Reserve, New Mexico. Now, John B. Slaughter isn’t to be confused with the famous rancher and lawman John Horton Slaughter.

The Slaughter cowboys were known to use the Hispanics in the area for target practice.

A young 19-year-old Mexican by the name of Elfego Baca got tired of this harassment, and got commissioned as a deputy sheriff to do something about it. One of the Slaughter cowboys, Charles McCarthy, shot at Baca. So, Baca arrested him. That evening some of the Slaughter cowboys tried to spring McCarthy loose. During the gunfight a falling horse killed one of the cowboys. The cowboys now felt justified in killing him.

On December 1, 1884 about 80 cowboys came after Baca. By now Baca had taken refuge in a tiny shack. For 36 hours the cowboys, surrounding the shack, filling it with bullet holes. They literally fired thousands of rounds at the shack. Supposedly, many as 400 bullets struck the door alone.

By nightfall Baca had killed a cowboy and wounded several others. By now the cowboys were sure Baca was dead. But they decided to wait until morning to go in after him. In the morning, the cowboys caught the smell of food cooking. It was Baca, cooking breakfast in what was left of the cabin.

Fortunately, for the cowboys, two deputies and several of Baca’s friends showed up, and they retreated. Elfego Baca was tried for killing one of the cowboys, and found innocent. He returned home, an obvious hero to the Hispanics of the area.

GOLD MINE SCAM

One of the keys to a great scam is for the scam artist not to appear to be as smart as the victim. This week’s story is about a couple of con men who were dumb like foxes.

One of the keys to a great scam is for the scam artist not to appear to be as smart as the victim. This week’s story is about a couple of con men who were dumb like foxes.

With the discovery of gold in California fake gold and silver mines became common. Swindlers and con men fooled many a greenhorn with “salted” mines. But there were few con men who did as great a job as two cousins from Kentucky named Philip Arnold and John Slack.

In early 1872 Arnold and Slack showed up in a San Francisco bank attempting to deposit a bag of uncut diamonds. When questioned about the diamonds, the two men immediately left with the diamonds. Curious, the bank’s director, William Ralston later found Arnold and Slack, and discovered that the diamonds came from a mine the men had found. The banker, assuming he was dealing with a couple of country bumpkins, schemed to take control of the mine.

A mining expert looked at the mine, and he reported back that it was rich with diamonds and rubies. The banker, Ralston, formed a mining company and capitalized it to the tune of $10 million. He was able to buy the country cousins off with a meager $600,000.

A young geographical surveyor by the name of Clarence King was suspicious of the stories he heard about the mine. It took him one visit to the mine to realize it had been salted…Some of the gems he found had already been cut by a jeweler.

On November 26, 1872 the whole scheme collapsed. Banker Ralston had to refund the investors, with much of the money coming from his own pocket. The two country bumpkins? They disappeared back in Kentucky, along with the meager $600,000 they had been given.

Incidentally, the young man who exposed the fraud, Clarence King, ended up becoming the first director of the United States Geological Survey.

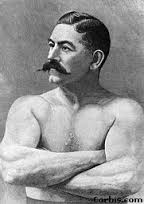

CARRY MOORE VS JOHN L. SULLIVAN

Carry Moore, the subject of today’s story was the only woman to be challenged by famous boxer John L. Sullivan, and accept that challenge. The outcome of that confrontation is interesting.

On November 21, 1867 Carry Amelia Moore married Dr. Charlie Gloyd. The marriage didn’t start out well, because the groom arrived drunk. And it seems he stayed drunk most of their marriage, which, incidentally, only lasted a year and a half. However this failed marriage ended up affecting a large portion of the population of this country.

On November 21, 1867 Carry Amelia Moore married Dr. Charlie Gloyd. The marriage didn’t start out well, because the groom arrived drunk. And it seems he stayed drunk most of their marriage, which, incidentally, only lasted a year and a half. However this failed marriage ended up affecting a large portion of the population of this country.

After the death of Dr. Gloyd, Carry Gloyd married a David Nation. Although David neither drank nor smoked, Carry found he had his share of problems, and he and Carry had a rocky marriage, with a number of separations.

By now Carrie Nation decided that a number of activities that men participated in were not good, including membership in the Masonic Order, sex, and especially strong drink. Even though Kansas was a dry state, there were a number of bootleg outlets. And Carrie took it on herself to “harass these dive-keepers.” The first place she attacked was actually a drug store, where she destroyed a barrel of “medicinal” whiskey.

Getting rid of her second husband, Carry was now free to spread her word beyond Kansas. She traveled the nation lecturing and destroying. When Carry was lecturing in New York, boxing champion John L. Sullivan, the owner of a beer joint said that if she ever entered his place he would “push her down the sewer.” Taking up the challenge Carry went to his place, and chased Sullivan into hiding in the men’s room where Carry refused to follow. A sign in another New York bar read, “All Nations Welcome Except Carry!”

Although Carry Nation was not able to see the ultimate fruit of her work, in 1919, just 8 years after her death, Prohibition became the law across the nation.

Death of Ned Christie

More firepower was used to kill the subject of today’s story that any other single man in the Old West. When you’re finished I think you’ll agree.

More firepower was used to kill the subject of today’s story that any other single man in the Old West. When you’re finished I think you’ll agree.

Ned Christie was a well-respected member of the Cherokee National Council. But he enjoyed his drink. And in May of 1887, after one such drinking spree, he was accused of killing Marshal Dan Maples. Ned protested his innocence. But, realizing he was getting nowhere, lit out on the run.

For about 6 years Christie was on the lamb. With the exception of one close call, the law just couldn’t catch him.

During this time virtually every crime that took place in the Indian Territory was blamed on him. Dime novels built his reputation to that of the most vicious man to ever raise a gun in the Indian Territory. He was reputed to have engaged in everything from peddling whiskey, to horse thievery and banditry. In the process, he was reputed to have killed as many as 11 people.

With a reward of $1,000 on his head, it was only a matter of time until someone collected it. And it happened on November 3, 1892. Marshal Heck Thomas trailed Christie to a log fort that he had built. Realizing the place was almost impregnable, Thomas sent for reinforcements. As well as plenty of ammunition, the reinforcements also brought along a three-pound field cannon.

During the assault more than 2,000 small-arm rounds were fired. They also shot 38 cannon balls. But they just bounced off. A heaver charge was used. It only succeeded in blowing up the cannon. Finally a dozen sticks of dynamite were placed next to the house. This did the trick.

With black smoke enveloping the area, Ned Christie came out of the house firing his rifle. The deputies returned fire, riddling Christie’s body. It may have taken as much armament as used in a major battle, but the law got their man.

DON’T KILL A MINISTER

As we all know, if someone kills a lawman, he’ll draw the attention of lawmen everywhere until he’s caught. In the Old West the same was true of ministers. And, that ain’t good.

As we all know, if someone kills a lawman, he’ll draw the attention of lawmen everywhere until he’s caught. In the Old West the same was true of ministers. And, that ain’t good.

Reverend F. J. Tolby was a Methodist circuit minister, who, in September of 1875, was traveling between Elizabeth and Cimarron in the New MexicoTerritory when he was waylaid and killed. Suspicion fell upon a mail carrier by the name of Cruz Vega. Cruz was arrested, and later, because of the lack of evidence, released

Friend and fellow minister, O. P. Mains was sure Cruz was the villain. So, he persuaded Clay Allison to talk to Cruz about the murder. You may remember Clay Allison being the subject of a couple of earlier stories. If not, just let me say that Allison was a maniacal killer. Using his own special method of persuasion, Allison was able to get Cruz to spill his guts. In the spilling, Cruz indicated that a Manuel Cardenas actually did the killing.

But, Allison and friends wanted someone to pay for the killing of Reverend Tolby, and unfortunately, Cardenas wasn’t around. So, on October 30, they decided to hang Cruz Vega. But, Clay Allison was a companionate person. So, while Cruz was choking to death, Allison shot him in the back, according to Allison “to put the poor Mexican out of his misery.” And even though Allison wasn’t a religious man, he evidently felt it was important to show people that no one should mess with a man of the cloth, so Allison cut Cruz down from the tree and drug him through town.

Manuel Cardenas was arrested and about ten days later vigilantes shot him to death.

I wonder if the following Sunday’s sermon of Reverend O. P. Mains, the man who started the killing spree, was on the sixth commandment.

BATTLE OF BEECHER’S ISLAND

The summer of 1868, Indians were conducting major raids on railroad work camps and homesteads. Major George Forsyth was ordered to put together a detachment of 50 volunteer frontiersmen to teach the Indians a lesson.

The summer of 1868, Indians were conducting major raids on railroad work camps and homesteads. Major George Forsyth was ordered to put together a detachment of 50 volunteer frontiersmen to teach the Indians a lesson.

The first part of September they arrived at Kansas’ Fort Wallace, and immediately took after a group of Indians who had stolen some stock. On September 16, Forsyth and his men, low on rations, camped on the banks of the Arikaree River.

Unknown to Forsyth 4,000, Cheyenne, Arapaho and Sioux had been following him for three days. The morning of September 17 Major Forsyth and his men were awaken by the sounds of war cries. The 50 volunteers, with their animals, retreated and dug into a 40-yard by 150-yard sandbar.

By 9 A.M. the Indians had killed all of the volunteers’ horses and mules. Now there was no way of escape. A half hour later 300-mounted warriors, headed directly for the 50 volunteers. But, what the Indians didn’t realize was that all of Forsyth’s men were equipped with Spencer seven-shot repeating rifles and Colt pistols. Waiting until the last second to start firing, the charge was broken.

For eight days the Indian attacks continued, and the Spencer rifles kept them away from the volunteers. Two of the volunteers were able to get away and make it to Fort Wallace for help. By the time reinforcements arrived, the bulk of the Indians had left, with only a small contingency staying to starve out the volunteers.

Technology had made it possible for 50 men to face and essentially defeat a force of 1,500 warriors. During the battle, 10 of the volunteers were killed, and 20 wounded. But Indian causalities were estimated to be around 50 killed and as many as 200 wounded.

CRAWFORD GOLDSBY

In the Old West it seemed necessary to have the appropriate name before a person could make a reputation. That sure was true wit h a man named Crawford Goldsby.

h a man named Crawford Goldsby.

If someone came into a bank in the Old West and announced, “I’m Crawford Goldsby, and this is a hold-up,” the teller would probably have laughed. That’s why you’ve never heard of outlaw Crawford Goldsby.

Crawford was born in 1876. His mother was a combination of black, Cherokee and white. His father was white, Mexican and Sioux. At the age of 16 Crawford had a dispute with a man who proceeded to whip him. He got a gun and shot him. Although it wasn’t fatal, Crawford hightailed it to the Indian Territory.

Next, Crawford came up with a name with a little more pizzazz. He became “Cherokee Bill.” Now he could build a reputation. And he wasted no time doing it.

On June 26, 1894 Cherokee Bill killed his first man…a posse member that was chasing him. His sister’s husband had beaten her. Shortly afterward, the brother-in-law was dead. Next a railroad agent was killed in a holdup. A railroad conductor was killed when he tried to throw Cherokee off a train. And then a bystander was shot during another holdup.

Cherokee Bill was finally arrested, brought before Hanging Judge Parker, convicted, and sentenced to hang.

Cherokee Bill walked up the 12 steps to the hangman’s noose. When he got to the top he looked at the crowd, smiled and said, “Look at the people. Something must be going to happen.” When asked if he had anything to say, he replied, “I came here to die, not to make a speech.”

He died at the age of 20, after killing almost 13 people in just two years…An obvious result of changing his name from Crawford Goldsby to Cherokee Bill.

MORGAN KILLED

1881 wasn’t a good time for the Earps with the O. K. Corral shootout in which Virgil and Morgan were seriously shot. And then later Virgil was shot again. It was hoped that 1882 would be a better year. But it wasn’t.

Morgan Earp was the youngest of the three Earps who participated in the O. K. Corral shootout. He was also the friendliest of the clanish Earps who were not known for having a smile on their face.

For a while in Tombstone, Morgan was a shotgun guard for Wells Fargo. But realizing dealing faro was more profitable and less dangerous, he got a job at the Occidental Saloon.

During the O. K. Corral incident Morgan was seriously shot through the right shoulder. Over the next few months he healed to the point that by the following March he could participate in his favorite activity, billiards.

It was March 18, 1882. Morgan and Wyatt had just attended a play. Afterward they went to Hatch’s Saloon so Morgan could play a game of billiards with owner Bob Hatch. As Morgan was chalking up his cue, two 45-caliber gunshots blasted through the saloon window. The first shot hit Morgan. The other barely missed Wyatt…Quite possibly both Morgan and Wyatt were both marked for assassination. But, as was the story throughout Wyatt’s life, the second bullet missed.

When the smoke cleared Morgan was on the ground in a pool of blood. The 45 had shattered Morgan’s spine. The doctors said there was no hope. With brothers Wyatt, Virgil, James and Warren by his side, Morgan said, “This is the last game of pool I’ll ever play.” Then he whispered something to Wyatt. Morgan was dead in less than an hour from the time he was shot.

Later Morgan was dressed in one of Doc Holliday’s suits and brother Virgil took him to Colton, California to be buried where his parents lived.

KANSAS CATTLE TOWNS

To Texas cattlemen Dodge City, Abilene, Caldwell, Ellsworth, Hays and Newton were all spelled with dollar signs.

They were the end of the trail for cattle drives. In reality, were it not for cattle and the cowboys, they would  probably have never grown beyond a few shacks and a dusty road.

probably have never grown beyond a few shacks and a dusty road.

But, on March 7, 1885, the Kansas legislature passed a bill that prohibited Texas cowboys and their cattle from coming into Kansas between March and December. What’s going on here?

Actually, four things…first, the future of Kansas’ “Cow Town” industry was very shaky at best. Railroads were being built directly to Texas, and soon Kansas railheads would no longer be needed. Second, it had been discovered that the plains of Kansas were good for more than just providing feed for passing cattle. Farmers were turning over the sod and planting crops. Although the cattlemen attempted to respect the farms, strays inevitably created havoc with crops. For some drives, conflict with farmers was a daily event.

The third, and probably most important reason was that Texas cattle were carriers of a tick fever. Over the years Texas cattle had become immune to the disease, and since it didn’t affect humans, there was no big concern. But, as the cattle passed through Kansas, ticks would leave the Texas cattle and infect the local dairy cows.

And then there was the preverbal straw that broke the camel’s back. The residents of these famous “Cow Towns” were getting fed up with the rowdy cowboys and the messy cattle.

So, the bottom line was that, as least this time, most of Kansas was behind this seemingly radical move by the legislature.

PEARL GREY

Pearl Grey was born on January 31, 1872. He was a talented baseball player, and played for the University of Pennsylvania while getting a degree in dentistry. Pearl was scheduled to follow in his father’s footsteps as a dentist. Looking for excitement, he played some semi-pro baseball. But that didn’t satisfy his need.

Incidentally, Pearl never liked his first name, which was thought by everyone to be a woman’s name. So he decided to change it to his mother’s maiden name, Zane.

Pearl, or as we know him now, Zane Grey never wanted to be a dentist. He wanted to be a writer. His first novel was a forgettable one about one of his ancestors. But his life was changed when in 1908 he met Colonel C. J. “Buffalo” Jones. Buffalo Jones convinced Zane to write his biography. So Zane could get a feel of the atmosphere of Buffalo Jones’ life, Jones took the 36-year-old writer out west.

While out west, Zane Grey experienced the excitement of the west, like roping mountain lions. Grey was fascinated with the people and landscape. The biography of Jones, “The Last of the Plainsmen” was completed that same year.

Although it got little attention, Zane Grey had found his calling.

About four years later Zane Grey published a novel that gained him lasting fame…Riders of the Purple Sage. This novel was about a weak easterner who became a man because of his exposure to the culture of the West. It was a theme that Zane would repeat in the almost 80 books he published during a life that lasted 64 years.

CLOTHES WASHING HINTS

FROM THE DECEMBER 21, 1897 TUCSON, ARIZONA DAILY STAR

In cold weather dry clothes indoors to prevent freezing.

A little kerosene oil put in the hot starch will prevent it from sticking.

Fold napkins square with the initials on the outside. They should also be ironed perfectly dry, and then put away nicely in the drawer.

Have plenty of the best soap, with borax, starch and bluing at hand. Add borax to the water in the proportion of one tablespoonful to a pail of water.

Sort your clothes in five grades. First, towels, table and bed linen; second, family linen; third, light-colored clothes; fourth, dark-colored clothes; fifth, flannels and stockings.

Colored cotton clothing of delicate shades should have the color set before washing. Add of salt a heaping tablespoonful to each pailful of cold water, and do not apply soap directly to the article.

A teaspoonful of borax to a quart of cold starch will make it stiff. Tablecloths should have as few creases in them as possible. Crease them twice lengthwise; have them very damp and iron them perfectly dry; fold over once or twice, according to their lengths, and place them carefully in a long drawer.

OLD WEST STORIES

I’ve done a number of short story videos for City 4, our local TV station. The stories are about people or events from the history of  our American West.

our American West.

Mel, the manager of the TV station has put several of them on YouTube. You can take a look at them by entering “Chronicle of the Old West” in the search line.

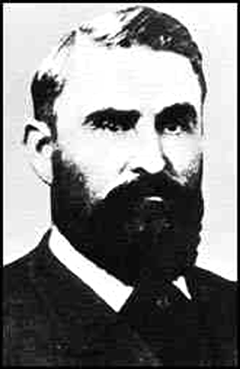

Incidentally, the picture isn’t of a wild man, but Al Sieber. Then again, after you hear his story you may think he was a wild man.

WHERE WHITE MAN WENT WRONG

Indian Chief “Two Eagles” was asked by a white U.S. government official, “You have observed the white man for 90 years. You’ve seen his wars and his technological advances. You’ve seen his progress, and the damage he’s do ne.”

ne.”

The chief nodded in agreement.

The official continued, “Considering all these events, in your opinion, where did the white man go wrong?

The chief stared at the government official then replied, “When white man find land, Indians running it, no taxes, no debt, plenty buffalo, plenty beaver, clean water. Women did all the work, Medicine Man free. Indian man spend all day hunting and fishing; all night having sex.”

Then the chief leaned back and smiled, “Only white man dumb enough to think he could improve system like that.”

BEING SCALPED

What follows is a December 20, 1883 article from the San Antonio Light newspaper. It’s the actual words of a soldier who had been scalped:

Quote…“I magine someone who hates you grabbing a handful of your hair and giving it a sudden jerk upward, and a not particularly sharp blade of a knife being run quickly in a circle around your scalp in a saw like motion. Also imagine what effect that a strong, quick jerk on your hair to release the scalp would have on your nervous and physical systems, and you will have some idea how it feels to be scalped.

magine someone who hates you grabbing a handful of your hair and giving it a sudden jerk upward, and a not particularly sharp blade of a knife being run quickly in a circle around your scalp in a saw like motion. Also imagine what effect that a strong, quick jerk on your hair to release the scalp would have on your nervous and physical systems, and you will have some idea how it feels to be scalped.

“When that Indian sawed his knife around the top of my head, first a sense of cold numbness pervaded my whole body. A flash of pain that started at my feet and ran like an electric shock to my brain quickly followed this. When the Indian tore my scalp from my head it seemed as if it must have been connected with cords to every part of my body.”…Unquote

Following the attack, a friend of the scalped man killed the Indian who had done the scalping, but, according to the soldier, his scalp wasn’t returned.

After recovery he chose to muster out of the service…but his commanding officer called him into his office, and suggested that the soldier was making a mistake by leaving the army. “Thank,” said his commanding officer, “how surprised and disgusted some red devil of an Indian might be if you should stay with us and happen to fall into his hands. When he went to raise your hair he would find that someone had been there before him.”

Incidentally, his commanding officer was General George Armstrong Custer whose command was wiped out shortly afterward at Little Big Horn.

CHARLES GOODNIGHT

Charles Goodnight was an early Texas cattleman who controlled up to 100,000 cattle on a million acres of land. But, one thing most people don’t know about Charles Goodnight is that he, more than anyone else, was responsible for cowboys “eaten’ good” while on the trail.

At the age of  20, he agreed to take care of a neighbor’s cattle…if he was allowed to keep every fourth calf. In four years, he had 180 head of cattle, and later he bought the neighbor’s whole herd.

20, he agreed to take care of a neighbor’s cattle…if he was allowed to keep every fourth calf. In four years, he had 180 head of cattle, and later he bought the neighbor’s whole herd.

It has been said of Goodnight that he “stole when he wanted to and lynched when he had to.” By the end of the Civil War, he had a herd of 8,000 cattle.

To keep his burgeoning empire…he did the lynching. One time his wife, expressing her shock over a vigilante hanging said, “I understand they hanged them from a telegraph pole!” Charles Goodnight responded, “Well, I don’t think it hurt the telegraph pole.”

Goodnight was an innovator who, throughout the years, raised Durham, Hereford and Anus stock. He even did some early experiments with what was then called “cattalo”…a crossbreed of buffalo and beef cow. Unfortunately, the calves were sterile and the mother often died in birth. However, Goodnight’s southern plains buffalo were later bred with northern ones to create the hardy strain of buffalo that now occupy Yellowstone and other areas.

In 1890, at the age of 54, he sold his ranching interests, spending the rest of his life as a “snowbird” with summers in Texas, and winters in Tucson, Arizona. Charles Goodnight passed away on December 13, 1929.

Oh yes, I mentioned that Charles Goodnight was responsible for cowboys “eaten’ good” on the trail. It was Charles Goodnight, who in 1866 took a surplus Army wagon, and revamped it into the first chuckwagon.

WOMAN’S SUFFRAGE

Although women had been instrumental the development of our country, as 1869 was coming to a close, they didn’t have the right to hold a political office, or even vote.

But that was changed on December 10, 1869 as the first state gave women the right to vote and hold political office. One would expect that it would be an eastern state…Quite possibly in the New England area. But that wasn’t so. It was probably one of the most frontier areas of that time…Wyoming. So, why Wyoming? Why were the men in the Wyoming Territory so progressive when it came to women’s rights?

One major backer, a middle-aged territorial legislator by the name of William Bright backed the bill because his wife convinced his that “denying women the vote was a gross injustice.” Incidentally, the progressive wife happened to be about half his age. Then there was Edward Lee, the territorial secretary, who argued that if a black man can vote, why couldn’t his dear sweet mother. But most people supported the bill for another reason.

At the time the Wyoming territory had a population of about 7,000 adults. Of those 7,000 adults, only about 1,000 were women. And most of those extra 6,000 men were lonely for the companionship of a woman. So, it was thought that if Wyoming gave women the right to vote, the territory would get national publicity, and in turn women…particularly single women would come to this rugged, isolated area.

When Governor John Campbell signed the bill one lawmaker gave the toast, “To the lovely ladies, once our superiors, now our equals.”

Did it work? Well, if you visit Wyoming today you’ll meet some of the handsomest, most strong-minded women, and happiest men in the United States.

1800’S BREAKFAST DON’TS

The December 9, 1897 Daily Star Newspaper in Tucson, Arizona Territory had the following recommendations for breakfast don’ts. They happen to be good advice for us even today.

BREAKFAST DON’TS

Don’t serve a breakfast on any but a fresh tablecloth.

Don’t expect fresh coffee if you are half an hour late.

Don’t comment on the bills you receive in the morning’s mail.

Don’t ask the man of the house what he would like for dinner.

Don’t ask your husband how much money he intends to leave you for the day’s expenses. After dinner is a better time to settle the financial question.

Don’t become so engrossed in the newspaper that you can’t address a remark to anyone.

Incidentally, this was one of the items in the December 2013 Woman’s Sphere from Chronicle of the Old West.

HARVEY WHITEHILL

Sometimes Old West lawmen chased an outlaw only until he was out of sight. He was lucky. Then there were the unlucky outlaws that were chased by Harvey Whitehill.

As a yo ung man, Harvey Whitehill mined in several areas in Colorado, and following the Civil War did some mining in New Mexico. As one of the founders of Silver City, New Mexico, he ended up as their sheriff. Whitehill came into the spotlight as the first person the arrest a young William Bonney for a petty theft. Bonney was to later became famous as Billy the Kid.

ung man, Harvey Whitehill mined in several areas in Colorado, and following the Civil War did some mining in New Mexico. As one of the founders of Silver City, New Mexico, he ended up as their sheriff. Whitehill came into the spotlight as the first person the arrest a young William Bonney for a petty theft. Bonney was to later became famous as Billy the Kid.

But, Sheriff Whitehill’s true nature came out following a November 24, 1883 train robbery. Four men held up a Southern Pacific train near Deming, New Mexico. In the process, the train’s engineer was killed.

Wells Fargo and Southern Pacific placed a reward of $2,000 on the head of each of the robbers. This whetted the appetite of semi-retired Sheriff Whitehill. Whitehill searched the scene of the crime and found a discarded out of the area newspaper. He traced it back to the subscriber, who was a storekeeper. The storekeeper remembered using it to wrap some food bought by a local Black cowboy named George Washington Cleveland.

Whitehill found Cleveland at a restaurant where he was working. Immediately Whitehill arrested him. Although Whitehill had no idea who else was involved in the train robbery, he said, “I arrested you for killing that train engineer. I already have your partners and they talked.” After that, Cleveland spilled his guts. The other three outlaws were arrested.

But, the four didn’t get a chance to go to trial…because they escaped from jail. When the posse caught up with them Cleveland was killed, and two others were captured, only to mysteriously die at the end of a rope on their way back to jail. Although the fourth person temporarily escaped, he was eventually captured.

BILLY CLAIBORN

Sometimes in life a person needs to let well enough alone, and not push an issue. Billy Claiborne should have learned that lesson.  Unfortunately, on November 14, 1882 he didn’t let well enough alone, and paid the ultimate price.

Unfortunately, on November 14, 1882 he didn’t let well enough alone, and paid the ultimate price.

Billy Claiborne was born in Louisiana in 1862. He came out west where he worked for cattleman “Texas” John Slaughter.

Billy was a cocky young man who would swagger when he walked. And he carried two guns. His friends started calling him “Billy the Kid” after the real “Billy the Kid”. Billy Claiborne liked the name, and so did the girls. He even started referring to himself as “Billy the Kid” Claiborn.

Now, as time passed, Billy wandered down to Tombstone, Arizona and there he hooked up with the McLaurys and Clantons.

On October 26, 1881 “Billy the Kid” Claiborne found himself with the McLaurys and Clantons in a Tombstone, Arizona alley facing the Earps and Doc Holliday. Realizing the desperate situation, Claiborn bugged out just before the shooting started.

Now, this is where Billy Claiborne should have left well enough alone, and high-tailed it out of town for a place where tempers were not raging. But, Billy wasn’t that smart.

After the shootout at the O. K. Corral, and the death of Virgil Earp at the hands of the cowboys, Wyatt Earp declared vengeance against all cowboys. One member of Wyatt’s posse was Buckskin Frank Leslie. During the cowboy roundup, one of the more prominent cowboys, Johnnie Ringo was killed, and Billy Claiborne thought the gunman was Buckskin Frank.

So on November 14, 1882 Billy Claiborne came after Buckskin Frank. Billy shot twice, and missed. Buckskin Frank shot once, and hit his mark.

As Buckskin Frank walked up to Billy, Billy said, “Don’t shoot again, I am killed.” An observer was heard to say, “Sure weren’t no Billy the Kid. He missed at thirty feet.”

RENDEZVOUS

The idea of the rendezvous was not that of a mountain man, but William Ashley, a St. Louis, Missouri merchant on a venture west. Ashley decided to cut out the competition for furs by going to Wyoming where the mo untain men were, instead of waiting for the furs to come to St. Louis.

untain men were, instead of waiting for the furs to come to St. Louis.

So on November 10, 1824 William Ashley left St. Louis for Wyoming. It was a six-month trip.

Since mountain men had little use for money, William took traps, weapons, trade goods, supplies and especially liquor. And he marked up the cost of goods as much as twenty times their eastern price, and he paid less than half the St. Louis price for the plews, as the mountain men called the beaver pelts.

But the mountain men didn’t care, this was a chance for these normally solitary men to relax, drink, gamble, drink, womanize and drink. It was an opportunity to rekindle relationships with other mountain men that they hadn’t seen for a year or more. And discover those who had gone to the rendezvous in the sky.

Several thousand Indians also showed up for the party. Even though some of the Indians and mountain men were mortal enemies, the rendezvous was a place of truce.

There were about 15 rendezvous over a period of that many years. By then trading posts, forts and civilization found their way in the remote sections of the west and beaver pelts lost their value. Some mountain men returned to civilization; others came out of the mountains to kill buffalo on the plains; still others went further back into the mountains, never to be heard from again.

DOC HOLLIDAY

The Old West’s most famous doctor didn’t become famous for saving lives, but taking them. His name was Doc Holliday. And on November 8, 1887 he died not achieving the one thing that he tried to accomplish most of his adult life.

Doc Holliday grew u p in Georgia where he went to dental school and started a practice. But soon after he developed tuberculosis and started heading west for a dryer climate.

p in Georgia where he went to dental school and started a practice. But soon after he developed tuberculosis and started heading west for a dryer climate.

For Doc Holliday dentistry was more like an avocation with gambling his profession. Doc Holliday gravitated to where the action was: Dallas, Texas, Cheyenne, Wyoming, Dodge City, Kansas and Tombstone, Arizona.

And during his travels, Doc Holliday and Wyatt Earp became friends. Although they both displayed uncanny nerve at times of crisis, in most ways they were different. Wyatt Earp tended to be calm and laid back. He preferred to fight a person with his fists or pistol-whip them…resorting to shooting only if he found no other way to defeat his opponent.

On the other hand, Doc Holliday was a hothead. At 5’ 10” Doc was a frail looking man weighing less than 150 pounds. He wanted to stay away from any physical confrontation.

Of all the shootings Doc Holliday was involved in, the O. K. Corral shootout was the most famous. It’s generally accepted that at the O. K. Corral, Wyatt’s objective was to pistol whip the cowboys…whereas Doc Holliday wanted to kill them, and he probably fired the first shot.

In the late 1800’s tuberculosis wasn’t curable, and most people with it became bedridden with a slow death…Doc Holliday’s adult life was spent with the secret hope that he would be shot and killed before he became an invalid.

This was his greatest failure. Because on November 8, 1887 Doc Holliday died in bed at a Glenwood Springs sanatorium. His last words reflected his since of humor and a realization of his failure. With Doc’s last breath he supposedly said, “This is funny.”