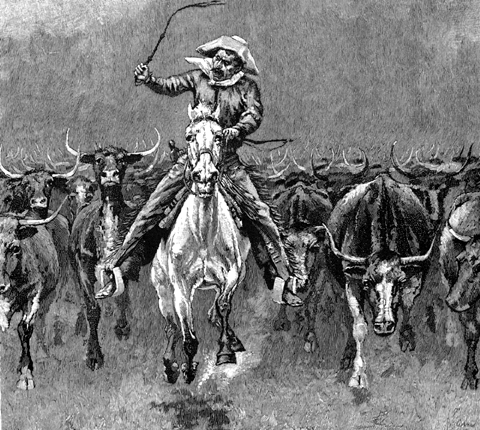

When it came to the Kansas Trail Drives, it seems that Kansas had a love-hate relationship with Texas cattle and the cowboys that brought them up.

When it came to the Kansas Trail Drives, it seems that Kansas had a love-hate relationship with Texas cattle and the cowboys that brought them up.

The love part was the profits to be made providing supplies to the cattle drives and a good time to trail-weary cowboys. Frontier struggling towns like Dodge City, Caldwell, Ellsworth, Hays, and Newton competed with Abilene to be the top “Cow Town” of Kansas.

But, as Kansas started getting less “frontier” and farming became more important, residents, anxious to attract businesses other than saloons and places of ill repute, started getting less enamored with the Texas cattle industry.

Although the Texas cattlemen tried to stay away from cultivated farmland, according to one cowboy “there was scarcely a day when we didn’t have a row with some settler.”

In addition to this, the Texas cattle carried a tick fever and hoof-and-mouth disease for which they were immune, but the Kansas cattle weren’t.

So, on this date back in 1885 the Kansas Legislature passed a bill that barred Texas cattle from the state between March and December 1.

This, along with the closing of open range with barbed wire fences, signaled an end to the cattle drives to Kansas.