Old West outlaw history has many “kids”, and the Sundance Kid is among the most popular. He teamed up with Butch Cassidy, and the two robbed banks, blew up railroad cars, stole money, buried loot, rustled horses, broke jail and foiled lawmen all the way from the United States to South America.

Old West outlaw history has many “kids”, and the Sundance Kid is among the most popular. He teamed up with Butch Cassidy, and the two robbed banks, blew up railroad cars, stole money, buried loot, rustled horses, broke jail and foiled lawmen all the way from the United States to South America.

Along the way many romanticized stories cropped up. Books, magazine articles, and even one popular movie had Butch and Sundance appearing in a variety of exciting situations. lt is true they belonged to The Wild Bunch, or Hole in the Wall Gang of robbers and rustlers in Old Wyoming. At one point in their career, they brazenly posed for a group photograph in a New York studio with members of their gang.

They rode hard, shot straight, plotted brazen holdups and get-aways, and even ran with a beautiful and mysterious woman known as Ethel (or Etta) Place. She traveled from New York to South America with them, was thought to be a Texas soiled dove, but disappeared from history before the men were hunted down and killed in Bolivia. All the possibilities surrounding Ethel’s life and what might have ultimately happened to her are explored here.

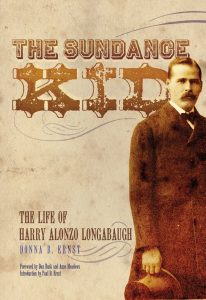

The author of this book is Donna Ernst, a member through marriage of the Longabaugh family, and she has spent many years delving into historical archives, family records, Pinkerton documents, letters and news accounts. Ernst has determined to set the story straight and takes the reader step by step from Harry Longabaugh’s childhood all the way to his death in Bolivia. She explains her sources of information and covers thoroughly Harry’s movements from childhood, to his work as an honest cowboy horse trainer, to his involvements in crime. She corrects some information about crimes he was blamed for, but other escapades she shows what part he played.

His crime spree began in the United States, and he spent some time in jail. Each time he was released he promised to go straight, but, but it always seemed too easy for him to drift back to a life of crime with his old pals. Eventually, when he was closely followed by American law enforcement authorities, he and Butch and Ethel departed for South America where they planned to become honest ranchers. However, the Pinkertons and other sheriffs were quick to figure out their whereabouts, and soon the trio was back on the run. They made friends in South America, but once they again began their outlaw ways, the locals naturally turned on them.

According to Ernst, down to their last two bullets, Butch and Sundance died of suicide in a shack surrounded by Bolivian police throwing Iead. Many writers show Burch and Sundance slipping back into the U.S. where they drifted in and out of their family’s lives. Several old men even claimed to be Butch or Sundance well into the 20th century. According to Ernst, one clever self-promoter may very well have been a Longabaugh relative, but certainly not Sundance himself.

The author makes a very strong case with good documentation that both Butch and Sundance died in Bolivia. This fascinating book takes the reader in a clear and concise writing style, along the outlaw trail of a man who might have been an upstanding, worthwhile citizen, but instead chose a life on the wild side.

This memorable book belongs in your Old West library. Get your copy HERE.

Publisher’s Note: The reviewer, Phyllis Morreale-de la Garza is the author of numerous books about the OId West including The Apache Kid, published by Westernlore Press, P0. Box 35305,Tucson, Arizona 85740.

*Courtesy of Chronicle of the Old West newspaper, for more click HERE.

Old West outlaw history has many “kids”, and the Sundance Kid is among the most popular. He teamed up with Butch Cassidy, and the two robbed banks, blew up railroad cars, stole money, buried loot, rustled horses, broke jail and foiled lawmen all the way from the United States to South America.

Old West outlaw history has many “kids”, and the Sundance Kid is among the most popular. He teamed up with Butch Cassidy, and the two robbed banks, blew up railroad cars, stole money, buried loot, rustled horses, broke jail and foiled lawmen all the way from the United States to South America.