In 1826 Stephen Austin authorized a force of men to fight Indians. This group was the inspiration that inspired the Texas Legislature to form the Texas Rangers on November 24, 1835. They were formed, not as a law enforcement group, but to protect the Texas frontier from

Comanche Indians and Mexican banditos crossing over the border. Why are they called Rangers? They were called Rangers because their job was to “range” over wide areas.

A private in the Texas Rangers would receive $1.25 per day. With this he took care of his food, clothing, ammunition and horse.

When the Civil War broke out, Texas went on the side of the Confederacy. Although the Rangers, as a group didn’t join the Confederacy, some of the members did. They formed a group called “Terry’s Texas Rangers.” And incidentally, this group was credited with originating the rebel yell.

After the Civil War; the conquest of the Indians; and Texas becoming a state, the Texas Rangers became the law enforcement agency of Texas.

Probably the most unique individual job the Rangers engaged in involved

Judge Roy Bean, the law

west of the Pecos. The Texas Rangers liked Roy Bean because he always handed down swift judgments. His justice may have been convoluted, but it was immediate, leaving the Rangers free to bring in more lawbreakers.

In 1896 Judge Bean was putting on a heavyweight prizefight, which was highly illegal in Texas. Although the fighters and the fans came from the U. S., the actual fight took place on a river sandbar just inside Mexico.

Making sure that all Texas laws were observed, a group of Texas Rangers stood on the Texas border, and observed the fight that, unfortunately, only lasted 90 seconds.

November 29, 2018 | Categories: Old West Myth & Fact | Comments Off on Texas Rangers: Why Are They Called Rangers?

Moses Embree Milner was a well-built man, more than 6 feet in height. Not only did he constantly smoke a pipe, he chewed tobacco at the same time. In 1849, at the age of 20, he went to California like everyone else… for gold. Then he moved up to Oregon, and then to Montana where he acquired the name California Joe.

He then started doing some scouting for the military. In 1868,

George Custer made him chief of scouts for the Seventh Cavalry. But that job didn’t last long because California Joe went out the night of his appointment and got so drunk that he had to be hogtied and returned to camp lashed to a mule. The next day Custer fired him as chief, but kept him on as a regular scout.

In 1874 he accompanied Custer on his excursion into the

Black Hills of the Dakotas where gold was discovered. Although the discovery was to be kept a secret, it was supposedly California Joe who let the word out. It was probably during a drinking spree the night of his arrival back to civilization.

A year later California Joe accompanied Walter P. Jenney’s expedition into the Black Hills to confirm the discovery of gold, and open it for settlement. California Joe was able to stake out a homestead on the future site of Rapid city, South Dakota.

While in Nebraska, California Joe got into an argument with Tom Newcomb, and on October 29, 1876 Tom found California Joe looking the other way and shot him in the back. Because there was no law in the area Tom Newcomb was never tried, but two years later a couple of California Joe’s friends shot Tom in the back.

November 4, 2018 | Categories: Old West Myth & Fact | Comments Off on California Joe

Question: It’s so hot in the West and the Southwest during much of the summer that even today with air-conditioning, it can get downright uncomfortable. How did they beat the heat in the Old West?

Answer: There were several things people on the frontier did to make the hot, dry summers more bearable. In some cases they used ingenuity. In others it came with the territory. One that came with the territory was on the plains. With no lumber for homes, but plenty of territory or sod, they cut it into one foot by two foot rectangles and used the sod to make their homes. Although these “soddies” had a lot of drawbacks, they were warm in the winter and cool in the summer.

Answer: There were several things people on the frontier did to make the hot, dry summers more bearable. In some cases they used ingenuity. In others it came with the territory. One that came with the territory was on the plains. With no lumber for homes, but plenty of territory or sod, they cut it into one foot by two foot rectangles and used the sod to make their homes. Although these “soddies” had a lot of drawbacks, they were warm in the winter and cool in the summer.

Those frontiersmen who settled in areas with available lumber, built homes with overhanging porches on all sides. That way no matter where the sun was located, the overhang shaded the windows. The porch also provided a shady place to take a Sunday afternoon rest in a rocking chair. And on hot nights a sleeping bag thrown on the porch provided an area with a cool breeze and protection in case of a midnight shower. Cowboys living in bunkhouses often slept outside under the stars during the summer.

Even businesses found ways to keep their customers cool. Back in 1880’s the town of Florence, in southern Arizona, bragged of having the coolest tavern in the southwest. In the rear of the regular saloon, a tunnel had been dug in the ground. That cool cave was called the Tunnel Saloon.

October 14, 2018 | Categories: Old West Myth & Fact | Comments Off on Air Conditioning in the Old West – A Reader’s Question

Clay Allison can be truly called a psychopath. At the height of the Civil War when the Confederate Army was drafting into service anyone who could hold a rifle, Clay was released on a medical discharge because he was maniacal.

Ending up in

Cimarron, New Mexico in 1870 Clay and some other local citizens broke a man out of jail and lynched him in the local slaughterhouse. Not being satisfied, Clay grabbed a knife; cut the man’s head off; stuck it on a pole; and gave it to a local saloon owner to display in his establishment.

In 1875 Clay became involved in another lynching. This time the man was hanged from a telegraph pole. Without butcher equipment around, Clay dallied the end of the lynch rope around his saddle horn and dragged the corpse around town.

A lot of Clay Allison’s strange actions could also be credited to his fondness for strong drink. It seems that when Clay was “under the influence” he was inclined to take off his clothes; jump on his horse; and Lady Godiva around town. Then he would invite everyone into the nearest saloon for a round of drinks… Such a party animal.

Although Clay shot more than his share of men… usually when the confrontation was decidedly to his advantage, and knifed at least one. He didn’t go down in a blaze of glory like most gun fighters.

Clay Allison moved to the Pecos, Texas area, took a wife, started a ranch, and, for the most part, settled down. On July 3, 1887 he went into town for supplies. While there he stopped at the local tavern, and imbibed a bit more than he should have, because on the way home Clay fell off the wagon. A wheel rolled over him and broke his neck. He was dead within an hour.

September 17, 2018 | Categories: Old West Myth & Fact | Comments Off on Clay Allison – Old West Psychopath

Stagecoach driver Charley Parkhurst was about 5’7”, with tobacco stains on a beardless face, and only one eye… The other was lost while shoeing a horse.

One day a gang led by a road agent named Sugarfoot held up Charley’s stage. Incidentally, they called him Sugarfoot because he wore empty sugar sacks on his extra large feet. From this point Charlie started carrying a pistol. About a year later Sugarfoot and his gang tried to hold up Charley’s stage again. This time Charley drove the stage’s horses into the gang; drew a pistol; killed Sugarfoot; and wounded the other two members of the gang.

In spite of the flashy clothes, endless stories and friendliness, Charley was a loner. Charley slept in the barn with the horses; bathed in creeks away from people; and stayed away from women.

Due to rheumatism, Parkhurst gave up driving a stage; opened up stage stop in Watsonville, California; registered to vote; and became a normal citizen of the community.

Charley ended up getting tongue cancer. Refusing treatment with threats to blow the head off any doctor who came close, Charley Parkhurst died on December 28, 1879.

When the autopsy was done, an amazing discovery was uncovered. Charley Parkhurst was actually… a fully developed woman, and she had even had a baby when she was younger.

It seems that Parkhurst, as a young woman left alone to fend for herself, just figured out a way to make it in a male dominated world.

There’s one other accomplishment most people don’t think about when they hear the story of Charley Parkhurst. While a resident of Watsonville, California, Charley Parkhurst was the first woman in the United States to vote.

July 25, 2018 | Categories: Old West Myth & Fact | Leave A Comment »

SHE FREQUENTLY VISITS SING SING PRISON.

A Mysterious Woman Whose Repeated Visits

to the Famous Penal Institution Have

Excited Interest as to Her Identity.

February 9, 1894, Chief, Red Cloud, Nebraska – Sing Sing Prison has a mysterious woman visitor, but that is not remarkable, because seven-eighths of the visitors to the convicts there are women. They all have burdens of sorrow to bear, but rarely of their own making, and they come and go year in and year out, to see beloved ones whom the world does not love and has put behind bars. The gray prison walls hold all that is dear in life to these mothers, wives, sweethearts and sisters.

February 9, 1894, Chief, Red Cloud, Nebraska – Sing Sing Prison has a mysterious woman visitor, but that is not remarkable, because seven-eighths of the visitors to the convicts there are women. They all have burdens of sorrow to bear, but rarely of their own making, and they come and go year in and year out, to see beloved ones whom the world does not love and has put behind bars. The gray prison walls hold all that is dear in life to these mothers, wives, sweethearts and sisters.

The husband who has committed crime that his wife may have luxurious surroundings usually retains the affections of that wife, even when he dons stripes and is close cropped. The professional burglar often is a model family man and does not sever his family ties when he “does time.” The man who kills his fellow man for the affections of a woman and is paying the penalty for that crime has surely a right to expect that that woman will care enough for him to remember and visit him while he is the servant of the state.

Then there is mother’s love, never failing, never even wavering in its unassailable constancy, and that accounts for one-half the visitors to the Sing Sing convicts. Thirteen hundred men are confined at Sing Sing, and the army of women—sad women who are sad because of the thirteen hundred—must easily equal the convicts in number.

Many a romance brought to a tragic climax by the merciless hand of the law is suggested by these untiring visitors. Even the ubiquitous hackmen who infest the Sing Sing railway station seem to appreciate this, for when these unhappy ones alight from the trains and look uneasily and self-consciously about, the drivers realize intuitively the nature of their errand and treat them with a deference rarely met within their class. They approach respectfully, and in subdued tones say kindly, “To the prison, madam?” or, “Right this way to the prison.”

About one visitor only is there any mystery. Others give their names and go to see some convict who is known to the keepers. This one goes veiled, and no one knows who it is she goes to see.

A tall, lithe, graceful woman, attired all in black and wearing a heavy black veil, occupied a seat in a car directly in front of and opposite that of the writer recently.

She was uneasy and restless, though not obtrusively so; she carried herself with the fine reserve of a woman of breeding accustomed to do just such things. Sometimes she would look anxiously about the car, as if in fear of being recognized, though with her veil recognition, even by an intimate friend, would have been clearly impossible.

An old-time hackman at the Sing Sing station approached her as she alighted. She got into his ramshackle conveyance as if she had been in it before, and it rattled up the hill and over the stony road along the bluff to the prison a few hundred yards in advance of the equally noisy conveyance of the writer.

It was the hour at which the convicts, having finished their evening meal in the great feeding hall—it would raise the ghost of Brillat Savarin to call it a dining-room—march in lock-step to their cells, in long, single files. They come through the stone-flagged prison-yard with a steady, machine-like shuffle of their heavy prison shoes. Keepers stand about with heavy sticks in their hands.

By the entrance to the long granite building containing the tiers of cells are two great open boxes of bread. Each striped miserable reach out and takes a piece with his left hand as he passes. Slung on the right arm of each is an iron solp pail on which is painted the prisoner’s number. The shuffle of the slowly-moving line continues for perhaps twenty minutes, at the end of which time each of the 1,300 has, with his supper in one hand and his slop-pail in the other, been locked in his cell.

The woman had been shown to the yard, and stood, a keeper by her side, under the portico of the inhospitable-looking hospital building. The long lines of convicts marched toward her and turned not ten feet from where she stood, and marched past the bread-box into the building. She supported herself with one daintily gloved hand against the stone wall, and, leaning forward in an attitude of eager interest, faced down the approaching line.

She tapped the pavement impatiently from time to time with the tow of her neat boot.

Some one in that long line riveted her attention; but there were hundreds there, and the veil prevented any one from seeing which striped one it was.

The prisoners all turned away their heads as they passed the woman. Was it a prison rule that prompted this, or a sense of shame that has survived hardening crime? Not one did otherwise. Many faces flushed, and if any one in that line recognized the trim figure and graceful pose of the strange woman he could never be detected by the flush, for flushed faces were too numerous.

When the last man on the last line a Negro on crutches, who killed a policeman on Wall Street, had disappeared in the door, the woman was escorted out by the keeper. She thanked Principal Keeper Connaughton for his courtesy, which to all visitors, men and women, is always the same. Her voice was pleasant, and there were no tears in it. Her manner indicated nothing in particular, and certainly not grief. She was driven away to the station and returned to New York.

This woman’s visits occur once every two months. Sometimes the interval between them is longer, and sometimes, but seldom, she misses one.

She has been coming for nearly three years, and her visits are always at the same hour. She sees all the prisoners in their lockstep march, and no one connected with the prison knows her name. No one in the prison has ever seen her face.

There are two ways of accounting for the periodical visits of this mysterious unknown. She either loves or hates, with a greater love or a greater hate than ordinarily, someone of the Sing Sing convicts. Perhaps it is love that impels her to remain veiled, and thus to spare the object of her affections humiliation and shame. Unrequited love, perhaps, leads her to conceal her face. Possibly her hate of some one in that long line of erring men derives a certain pleasure from the sight of him in the moment of his disgrace.

Who can tell why she hides her face? Is it because of love or hate?

June 28, 2018 | Categories: Old West Myth & Fact | Leave A Comment »

It is said of Dave Mather that he spent as much time in jail as he did in the occupation of putting others there. Dave is known as “Mysterious” Dave Mather, because, supposedly little is really known about his life. But we know enough that if he notched his pistol each time he assisted in sending someone to their reward, he would have had to carry a couple of guns.

In 1876 he assisted in the lynching of an innocent man. In January of 1880 he killed two men and seriously wounded another. Three days later he killed another man. February of that year he helped lynch three men. In 1884, during a stint as a lawman in

Dodge City, he got crossways with Thomas Nixon and killed him. Dave was heard to mumble, “I ought to have killed him six months ago.”

An example of the scrapes Dave got into and his method of getting out of them happened on May 10, 1885. Mather had been playing cards in

Ashland, Kansas with a grocer named David Barnes. After Barnes won two out of three hands, Mather threw the cards at Barnes and picked up the pot of money. David Barnes pulled his gun and put a hole in Mather’s hat. Now, obviously, that wasn’t where he was aiming.

Meanwhile, Mather’s brother, who happened to be the bartender, pulled his gun and started shooting. Dave Mather did likewise. When the shooting stopped, and the room cleared of gun smoke, David Barnes, the card player, was dead… and two innocent bystanders had holes in their legs.

The Mather brothers were arrested. But, after posting a $3,000 bond, Dave mysteriously rode out of town to seek more notches for his gun. And so was born the legend of Mysterious Dave Mather into the lore of the Old West.

June 25, 2018 | Categories: Old West Myth & Fact | Leave A Comment »

This is an interview by Henry M. Stanley, African explorer who uttered the famous line “Dr. Livingston, I presume?” He met James Hickok while working for the Weekly Missouri Democrat. At the time of his interview with Wild Bill Hickok he was a scout for the Seventh Calvary.

This is an interview by Henry M. Stanley, African explorer who uttered the famous line “Dr. Livingston, I presume?” He met James Hickok while working for the Weekly Missouri Democrat. At the time of his interview with Wild Bill Hickok he was a scout for the Seventh Calvary.

April 4, 1867, Weekly Missouri Democrat – James Butler Hickok, commonly called “Wild Bill” is one of the finest examples of that peculiar class now extant, known as Frontiersman, ranger, hunter and Indian scout. He is now thirty-eight years old and since he was thirteen the prairie has been his home. He stands six feet one inch in his moccasins and is as handsome a specimen of a man as could be found. Harper’s correspondent recently gave a sketch of the career of this remarkable man which excepting a slight exaggeration, was correct.

We were prepared, on hearing of “Wild Bill’s” presence in camp, to see a person who would prove to be a coarse, illiterate, quarrelsome, obtrusive, obstinate bully; in fact one of those ruffians to be found South and West, who delights in shedding blood. We confess to being greatly disappointed when, on being introduced to him, we looked on a person who was the very reverse of all that we had imagined. He was dressed in a black sacque coat, brown pants, fancy shirt, leather leggings and had on his head a beaver cap. Tall, straight, broad compact shoulders, Herculean chest, narrow waist, and well formed muscular limbs. A fine handsome face, free from any blemish, a light moustache, a thin pointed nose, bluish-gray eyes, with a calm, quiet almost benignant look, yet seemingly possessing some mysterious latent power, a magnificent forehead, hair parted from the center of his forehead and hanging down behind the ears in long silky curls. He is brave, there can be no doubt; that fact is impressed on you at once before he utters a single syllable. He is neither as coarse nor as illiterate as Harper’s Monthly portrays him.

The following verbatim dialogue took place between us: “I say Bill, or Mr. Hickok, how many white men have you killed to your certain knowledge?”

After a little deliberation, he replied, “I would be willing to take my oath on the Bible tomorrow that I have killed over a hundred a long ways off.”

“What made you kill all those men; did you kill them without cause or provocation?”

“No, by Heaven! I never killed one man without a good cause.”

“How old were you when you killed your first man, and for what cause?”

“I was twenty-eight years old when I killed the first white man, and if ever a man deserved killing he did. He was a gambler and counterfeiter, and I was in a hotel in Leavenworth City then, as seeing some loose characters around, I ordered a room, and as I had some money about me, I thought I would go to it. I had lain some thirty minutes on the bed when I heard some men at the door. I pulled out my revolver and Bowie knife and held them ready, but half concealed, pretending to be asleep. The door was opened and five men entered the room. They whispered together, ‘Let us kill the son of a b—h; I bet he has got money.’

“Gentlemen,” he said further, “that was a time, an awful time. I kept perfectly still until just as the knife touched my breast; I sprang aside and buried mine in his heart and then used my revolvers on the others, right and left. Only one was wounded besides the one killed; and then, gentlemen, I dashed through the room and rushed to the fort, procured a lot of soldiers, came to the hotel and captured the whole gang of them, fifteen in all. We searched the cellar and found eleven bodies buried there-men who had been murdered by those villains.”

Turning to us he asked, “Would you have not done the same? That was the first man I killed and I was never sorry for that yet.”

May 31, 2018 | Categories: Old West Myth & Fact | Leave A Comment »

From 1879 to 1881 James Masterson, Bat Masterson’s older brother, was the marshal of

Dodge City. However, on April 6, 1881, because of a change in city government, James was dismissed. However, this wasn’t James’ only income. He owned a piece of the Lady Gay Saloon. His partner was an A. J. Peacock. Now, theirs wasn’t the most cordial partnership. Peacock had hired his brother-in-law, Al Updegraph as bartender, and James didn’t like it. On April 9, the dislike turned to gunshots between James, Peacock and Updegraph. In this Masterson – Peacock shootout no shots hit their mark, but the damage was done.

Like with many a schoolyard squabble, I’m sure James probably said something like, “I’m going to tell my brother, and he’ll beat you up.” Because right after the incident, Bat Masterson, who was in

Tombstone, Arizona at the time, jumped on a train, and traveled the 1,100 miles to Dodge City to avenge his brother.

Peacock obviously knew that Bat was coming, because Peacock and Updegraph were waiting for Bat when his train arrived on April 16. Guns were drawn, and bullets started flying. Soon more gunshots were heard from another direction as some of Peacock’s friends enter the fray. And then more shots as James Masterson and his friends joined into the rukus.

As the shootout participants were reloading their empty guns, the mayor and the sheriff showed up with loaded shotguns, and demanded the shootout stop. Which it did. Unfortunately, brother-in-law, Updegraph was killed during the shooting.

The outcome of the Masterson – Peacock Shootout was that Bat Masterson was arrested, and charged for discharging a pistol upon the streets of the city. He pleaded guilty, and was fined $8 in costs. Bat paid the fine, and the two Mastersons wisely left town on the next train, and onto more incidents to add to their legend.

May 23, 2018 | Categories: Old West Myth & Fact | Leave A Comment »

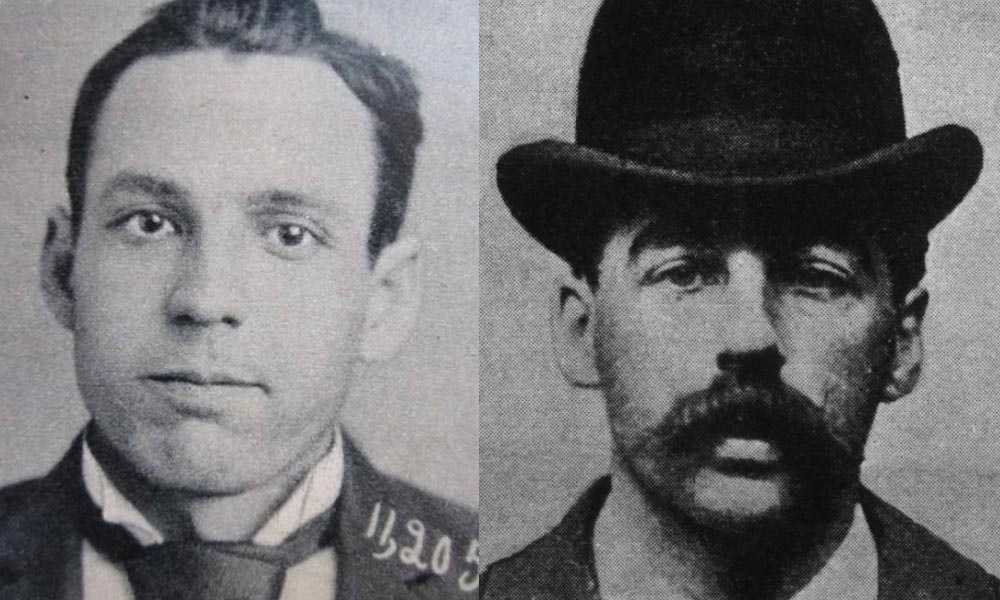

Marion Hedgepeth was born and raised in Missouri. As a young man, he went out west to Montana, Wyoming and Colorado where he learned the art of rustling, robbery and killing. Afterward, Marion headed back to St. Louis where he formed a gang known as “The Hedgepeth Four.”

Marion was one of the most debonair outlaws ever to appear on a wanted poster. He was always immaculately groomed with slicked down hair hidden by a bowler hat. He wore a well-cut suit with topcoat. His wanted poster noted that his shoes were usually polished.

The Hedgepeth Four committed a series of train robberies. Eventually Marion was caught and put on trial. Because of his dapper dress and good looks, the courtroom was filled with women and his cell was filled with flowers. But he was still sentenced to 25 years in the state prison.

While waiting for transfer to prison, Marion’s cellmate was a

H. H. Holmes, who was awaiting trial for swindling. Holmes confessed to Marion that he had murdered several women. Marion shared the information with the authorities, hoping it would lighten his sentence. This, along with petitions from women, got him pardoned after 12 years.

Riddled with tuberculosis, Marion continued his life of crime, and was arrested in Nebraska, where he served two more years. Now a physical wreck, on the evening of December 31, 1910 Marion entered a Chicago saloon with the objective of robbing the cash drawer. Unfortunately, a policeman interrupted the robbery, and Marion was shot dead.

Hearing of his death,

Allan Pinkerton said of Marion Hedgepeth, “He was a bad man clear through.”

April 28, 2018 | Categories: Old West Myth & Fact, Uncategorized | Leave A Comment »

The stories of the bravery of the

Texas Rangers are legendary. However, there was one incident when a group of them were cowards. It was when events made the Texas Rangers surrender.

About ninety miles east of El Paso, Texas, are salt beds where people went to gather this essential mineral, not only for food, but also for silver mining. In 1876, Charles Howard tried to get control of the salt beds by filing a land claim on them. The salt gathers living in the area didn’t like this. In a confrontation, Howard killed one of their leaders. This caused an uproar. Texas Ranger major John B. Jones was sent to investigate. Seeing the need for more help, he organized Company C of the Texas Rangers.

To be fair, the men he recruited were toughs from Silver City, New Mexico, and the man he put in charge, John Tays, was no leader. Under normal circumstances, none of these men would have met the

Texas Ranger standards. But, these weren’t normal circumstances.

On December 12, Tays and the other Rangers entered San Elizario. As soon as they got there, the salt gathers knifed to death the local storeowner. The Rangers did nothing. The next morning a sniper shot their sergeant. With the Rangers under siege, they surrendered to the mob.

The Rangers were locked up in a building and then the salt gathers killed anyone they thought was against them. After the killing was done the Rangers were released to return home the best way they could.

Within days military troops showed up, but by then all of the killers had fled south of the border.

Never before, nor since have the Texas Rangers stood by and watched crimes take place, or surrendered without a fight.

April 14, 2018 | Categories: Old West Myth & Fact | Leave A Comment »

Buffalo Bill Cody was born William Frederick Cody, and at the age of 11 his father died. As the middle child of seven brothers and sisters, William Cody had to go to work to help support his family. His first job was carrying messages on horseback between wagon trains for a freight company. For a while he was a rider for the

Pony Express where he became acquainted with his lifelong friend, Wild Bill Hickok.

After failing at running a boarding house, he got a job killing buffalo to feed the workers on the

Kansas Pacific Railroad. This is where he got his nickname “Buffalo Bill.” The railroad workers who called him by that name didn’t do so as a compliment. They got so tired of buffalo meat that when they saw him they would say, “Here comes that ‘Buffalo Bill.’”

In 1872, now known as Buffalo Bill Cody, he starred in a play entitled “The Scouts of Prairie.” Although he had a couple more stints as a scout for the army, his head was in show business. In 1882 “Buffalo Bill’s Wild West Show” appeared for the first time.

In 1887 he took the show to England. In 1889 he went on a tour of Europe… And again in 1891 his “Wild West Show” went back to Europe. The European citizens were enthralled with the Indians, the skills of the cowboys and wildness of the west.

Inspired by

Buffalo Bill Cody, Europe has had a love affair with the

Old West, even through two world wars. It’s interesting that although they were inspired by the theatrics of Buffalo Bill’s show, they, much more than American

Old West re-enactors, strive for authenticity in their attire and reenactments.

April 11, 2018 | Categories: Old West Myth & Fact | Leave A Comment »

May 9, 1885, Arizona Champion, Phoenix, Arizona – The Kansas City Journal tells of a game of poker played recently in that city between a Texan and Major Drumm. The Texan had no money, but plenty of cattle and an immense desire to play poker with the Major. The latter is known around the stock yards for his great natural resources, and he swept away the seemingly insurmountable difficulty by proposing a game of one steer ante, two steers come in and no limit. They played poker for cattle on this basis.

May 9, 1885, Arizona Champion, Phoenix, Arizona – The Kansas City Journal tells of a game of poker played recently in that city between a Texan and Major Drumm. The Texan had no money, but plenty of cattle and an immense desire to play poker with the Major. The latter is known around the stock yards for his great natural resources, and he swept away the seemingly insurmountable difficulty by proposing a game of one steer ante, two steers come in and no limit. They played poker for cattle on this basis.

Major Drumm dealt and the gentleman from Texas anteed one steer. Both came in and the game opened with four steers on the table. Major Drumm drew two tens and caught an unexpected full, while the gentleman from Texas struck a bobtail snag and passed out.

The third was a jackpot and it took three deals to open it. The gentleman from Texas finally drew two jacks and opened the pot with a fine breeding bull, which counted six. Major Drumm covered this with five steers and a two-year-old heifer, and went him twelve better. The gentleman from Texas, who drew another jack, saw the twelve cows and went him fifty steers, twenty two-year-old heifers, four bulls and twenty-five heifer calves better. Major Drumm looked at his hand and placed upon the table six fine Alderney cows, five imported Durham bulls, one-hundred grass-fed two-year-olds, fifty prime to medium corn-fed Colorado half-breed steers, with a side bet of a Normandy gelding to cover the bar bill. The man from Texas made his bet good with an even two hundred and fifty straight Kansas wintered Texas half-breeds and ten Scotch polled cattle, fourteen mustangs and the northeast ¼ of the southwest ¼ of section 10 of the Panhandle of Texas, and called.

Major Drumm held three aces, and put in his hip pocket 750 steers, heifers, etc., and a big stock ranch.

March 5, 2018 | Categories: Old West Myth & Fact | Leave A Comment »

Reprinted from Dakota Livesay’s Chronicles of the Old West column in Cowboys & Indians magazine:

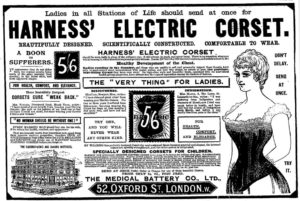

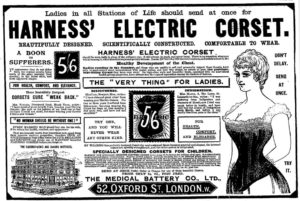

November 5, 1890, Enterprise, Riverside, California – I’ve always been opposed to this promiscuous courting; this vicious system which permits a young man without any intentions to waste a girl’s time with his attentions. At last I have devised a remedy. The electrical corset solves the difficulty. It will no longer be possible for a young man to slip his arm around a girl’s waist or lay his head upon her shoulder without giving the alarm. The “ting-a-ling-ling” will instantly bring her pa, ma or big brother into the room, and the offender will be summarily ejected.

The electrical corset has a great future. Its influence upon the moral tone of society is destined to be incalculable. We shall have no more of these hasty marriages, which end so speedily. Many a young man under the inspiration of the moment when his arm is encircling a girl’s waist breathes a love, which he would otherwise have left untold. This is all wrong. The electric corset will put an end most effectually to this practice.

But let parents be on their guard. These boys will devise means to beat the electric bell of this new corset, just as the conductors did the bell punch.

February 25, 2018 | Categories: Old West Myth & Fact | Leave A Comment »

It was 1864 in Jackson County, Missouri. Two men, Dick Merrick and Jeb Sharp had murdered a horse trader by the name of John Bascum. The two men were arrested and put on trial. The jury found them guilty. The judge sentenced them to be hanged from the gallows. And, he said it must be done within twenty-four hours…There wasn’t much of an appeals process in the Old West.

So, on September 6, the townspeople frantically started building a gallows. Just before the twenty-four hour deadline was up, the two men were grabbed, sacks were put over their heads, and they were led to the gallows. Ropes were placed around their necks. The trap door sprung. Before the deadline, their lifeless bodies were hanging from the end of ropes. The townspeople congratulated themselves on a job well done.

Sheriff Clifford Stewart went back to his office to take care of the final paperwork. But, when he stepped inside his office, Sheriff Stewart had the surprise of his life. There in the cell were the murders Dick Merrick and Jeb Sharp. At first, he thought it surely was a mirage. But it wasn’t.

Within a matter of hours, the situation had been sorted out. It seems that the night before two men had been arrested for drunkenness, and the anxious citizens had grabbed them by mistake. The men were still to drunk to protest, and Merrick and Sharp sure weren’t going to tell anybody they had the wrong men.

But that’s not the end of the story. Since the judge had required the sentence be carried out within twenty-four hours, and it wasn’t, the two killers were set free.

This story should persuade any person of the merits of living a temperate life.

February 12, 2018 | Categories: Old West Myth & Fact | Leave A Comment »

In the 1860’s when a pioneer family headed out west, they usually did it in a covered wagon pulled by horses or oxen. One man, Samuel Peppard, didn’t have horses or oxen, but that didn’t stop him. His idea was a Wind Wagon.

In the 1860’s when a pioneer family headed out west, they usually did it in a covered wagon pulled by horses or oxen. One man, Samuel Peppard, didn’t have horses or oxen, but that didn’t stop him. His idea was a Wind Wagon.

On May 9, 1860 Samuel Peppard headed out west. This was during the time of the Pike’s Peak gold rush, and Samuel wanted to do some gold prospecting. He didn’t have any horses or oxen, and he didn’t want the obligation and expense of taking care of them.

But, he did live in the Kansas Territory. And anyone who has been through Kansas knows it’s pretty flat, and the wind tends to blow rather strongly. Being a creative person, Peppard decided to take advantage of the resources at hand, and so he designed the world’s first wind-sailor. Built like a small boat, it was about 8’ long and 3’ wide, and it had four large wagon wheels. Weighing about 350 pounds, it was designed to hold 4 people.

The first time out, the wind blew the wagon over. So Peppard reconstructed the sails, rudder and brakes. By now everyone called it “Peppard’s Folly”.

With three of his friends aboard, Peppard raised the sails, and “Peppard’s Folly” took off across the prairie. Depending on the strength of the wind, it got up to 30 miles per hour.

On days when there was no wind, Peppard and his three friends just sat back, smoked a cigarette, and swapped stories.

They traveled about 500 miles before a dust devil came along and turned the wind wagon into a pile of rubble.

Peppard and his friends finally made it to Denver, but like most seekers of gold, they didn’t find anything.

Peppard later went back to Kansas, and lived to the ripe old age of 82. But he was always known as the guy who sailed to Denver.

January 29, 2018 | Categories: Old West Myth & Fact | Leave A Comment »

Temple Houston was the son of Texas’ founding father Sam Houston. He was an independent young cuss… so independent that at the age of 13, as a rawboned boy with shoulder length hair, he became a cowboy on a cattle drive from Texas to Montana.

On his way back home, Temple ran into a friend of his father’s who talked him into going to Washington D. C. and becoming a Senate page. After three years as a page, Temple decided to study law. So, he went back to Texas, enrolled in Baylor University and at the age of 19 got a law degree. Within a year he was practicing law… Now, I think we can all agree that Temple Houston packed a heck of a lot of stuff in those first 20 years. And he did slow down afterward.

On August 25, 1881, at the age of 21, Temple made a speech on the battle of San Jacinto, bringing tears to the eyes of the audience, and his first glimmer of fame.

Temple became the prototype of the modern day celebrity lawyer. He had a shooting match with Billy the Kid, which, Bat Masterson promoted. And Temple supposedly won.

Temple was married and moved to Woodward, Oklahoma where he got into a courtroom row with Al Jennings, which resulted in his killing two of Al’s brothers in a saloon brawl. While defending a woman accused of operating a brothel, he drew the Biblical parallel by saying, “as your Master did twice, tell her to go in peace.” And they did.

Back in Texas,

Temple Houston was a district attorney and served in the Texas state legislature. Until his death on August 15, 1905 at 45 years of age, Temple worked on only the most difficult cases. And there was the life of the son of Sam Houston.

October 29, 2017 | Categories: Old West Myth & Fact | Leave A Comment »

In 1876, Wyatt Earp became a policeman in

Dodge City, Kansas. A fellow policeman was Jim Masterson, Bat’s brother. On July 26, 1878, Wyatt and Jim were patrolling the streets. At about

3 o’clock in the morning three cowboys decided to head back to camp after a night of drinking. After picking up their pistols, they passed by the local dance hall. Thinking it would be a great joke, they fired several shots into the dance hall. Wyatt and Jim rushed to where the action was taking place. The cowboys immediately turned their guns on Wyatt and Jim. Had they not been plastered, they would have realized that up until then, what the cowboys had done would have just gotten them run out of town. However, with lead coming their way, both lawmen started shooting back.

The cowboys made it to their horses, and as they rode away both Wyatt and Jim emptied their pistols in their direction. Thinking they had missed, the policemen started walking away when George Hoy, one of the cowboys, fell from his saddle. Hoy had been shot in the arm. Hoy was taken to a doctor, and then jail. Unfortunately for him infection set into the wound and he died four weeks later.

Many historians credit Wyatt Earp for the kill even though, with lead flying, it couldn’t be positively determined if Wyatt or Jim’s bullet did the damage. And, with Hoy dying, from what could have been considered a minor wound, quite possibly, it was the doctor that did the killing. But, then, as far as George Hoy is concerned, no matter who did the killing, the results were the same.

October 12, 2017 | Categories: Old West Myth & Fact | Leave A Comment »

In the fall of 1892 Bill Doolin formed the Doolin gang that robbed trains and banks. He caused enough havoc to rile up the law in the area.

In the fall of 1892 Bill Doolin formed the Doolin gang that robbed trains and banks. He caused enough havoc to rile up the law in the area.

On September 1, 1893, the Doolin gang was resting in Ingles, Oklahoma, when the marshal of Guthrie got information on their location.

Disguised as hunters, about 13 deputies arrived in two covered wagons. Six of the Doolin gang were drinking and gambling in Murray’s Saloon. The seventh, Arkansas Tom, wasn’t feeling well, so he had retired to his room at the O.K. Hotel.

As the two wagons converged on the middle of town, “Bitter Creek” Newcomb left the saloon and jumped on his horse. Thinking Bitter Creek might get away, Dick Speed, one of the deputies, took a shot. It splintered Bitter Creek’s rifle stock.

The gunshots caused the ill Arkansas Tom to come to the window of the O.K. Hotel. He put three slugs in Dick Speed. With Arkansas Tom shooting from the second floor of the hotel and the rest of the gang shooting from the saloon, the deputies found themselves in a precarious position… which resulted in the members of the gang in the saloon being able to make a dramatic escape on horseback.

However, Arkansas Tom was still stuck in the hotel. After a threat to blow up the hotel with dynamite, Arkansas Tom surrendered on the condition he wouldn’t be lynched. Even though he had killed two of the deputies, the agreement was honored.

Although

this shootout has since been known as the Gunfight at Ingalls, it could very well have been known as the gunfight at the O.K. Hotel. But then another group who had a shootout in

Tombstone, Arizona eleven years earlier might have sued them for trademark infringement.

October 8, 2017 | Categories: Old West Myth & Fact | Leave A Comment »

Simone Jules was a young French girl who arrived in Northern California at the height of the gold rush. For about four years she worked as a soiled dove in San Francisco’s Bella Union. Accumulating enough money to open her own place, she headed up to Nevada City, California, changed her name to Eleanor Dumont and opened the Dumont Palace gambling saloon.

After a falling out with a male partner, who was getting a piece of both the gambling action and Simone, she turned to drink, and started moving around the mining camps in Nevada, again as a soiled dove. When Simone, was in her late 20’s the hair on her upper lip began to grow rather dark. One evening a drunken miner called her “Madame Mustache.” And to her chagrin, it stuck.

Later Madame Mustache sold all her gambling interests and bought a cattle ranch near Carson City, Nevada. Now in her early 40’s,

Madame Mustache was ready to settle down, and become a cattle rancher. But, along came a con man named Carruthers. Carruthers proceeded to romance Madame Mustache, marry her, have all her assets put in his name, sell the assets, and bug out faster than I was able to say it. But don’t worry; Carruthers didn’t get away Scott free. Madame Mustache caught up with him a little latter, and evened the score with two blasts from a shotgun.

With no money, Madame Mustache went back to working the gambling tables. Now in her late 40’s, with the hair on her face growing ever darker, her features those of a woman much older than her age, and her charm gone, on the evening of September 6, 1879 Madame Mustache took poison and died. She was just another victim of the harsh life of the Old West.

September 8, 2017 | Categories: Old West Myth & Fact | Leave A Comment »

In 1850 over 9,000 miles of track covered the Northeastern portions of the United States. By 1860 there were 30,000 miles, more than the rest of the world combined, and the tracks were extending to the Midwest.

In 1850 over 9,000 miles of track covered the Northeastern portions of the United States. By 1860 there were 30,000 miles, more than the rest of the world combined, and the tracks were extending to the Midwest.

As early as the 1840’s Congress began thinking about the possibility of constructing a transcontinental railroad. And then in 1848, with the discovery of gold in California, it became even more important.

Two companies got the contract. The California based Central Pacific started eastward, and the eastern based Union Pacific began in Omaha, Nebraska, moving west. In February of 1863 the great race began. For six years the two railroad giants headed toward each other. And on May 10, 1869 they met at Promontory, Utah.

Four special spikes were used for the ceremonial uniting of the rails…two gold, a silver, and one that was a blend of gold, silver and iron. The celebrities lined up to drive the spikes. After several misses, and several, not so subtle snickers from weather-hardened men who had been driving spikes for six years, at 2:47 p.m. the railroad was declared completed.

In Washington D.C. a magnetic ball on the Capitol dome fell. A 100-gun salute went off in New York City. The Liberty Bell rang in Philadelphia. 7,000 Mormons celebrated in Salt Lake City. And in San Francisco a banner waved, stating “California Annexes the United States.”

You may ask, “What happened to the ceremonial spikes?” Well, as soon as everyone left the area they were pulled and replaced with iron ones. Another interesting fact… the railroad wasn’t actually completed on that date. In order to meet the completion deadline they had skipped building a bridge over the Missouri River between Omaha and Council Bluffs.

June 25, 2017 | Categories: Old West Myth & Fact | Leave A Comment »

Supposedly, when Tiburcio was just 18, he killed a man. But since he was never arrested for this crime, it might be just a story he spread.

What is known is that at the age of 19 he was arrested for stealing cattle and sentenced to five years at San Quentin. The prison authorities probably should have designated a permanent Tiburcio Vasquez cell, for two months after he got out, Tiburcio was back at San Quentin on larceny charges. And almost as soon as he served his time for this crime, he was back, this time charged with armed robbery.

At the age of 32 Tiburcio got out of San Quentin. But he obviously had not learned his lesson, because he continued his life of crime. Two years after his last prison stretch, Tiburcio escaped a posse after being shot up following a stage robbery. Then a year later, while robbing a store with six cohorts, Tee-burr-see-o killed four unarmed men.

With a reward posted of $8,000 alive, or $6,000 dead, in 1874 Tiburcio was captured following a shootout in which he was shot six times. He was taken to San Jose, tried, convicted, and on March 19, 1875, this 5’ 7”, 130 pound terror of California was hanged.

June 11, 2017 | Categories: Old West Myth & Fact | Leave A Comment »

Dave Rudabaugh was born in Missouri in 1841. Early in life he moved to Kansas. At the age of 18, Dave started a gang that rounded up and sold other people’s cattle. By the age of 29 he and his gang moved on to robbing payroll trains and railroad construction camps.

Obviously, the railroad didn’t like Rudabaugh’s activities. So they hired Wyatt Earp to stop them. But Wyatt’s pursuit didn’t inhibit Rudabaugh’s activities. For in January of 1878 he and his gang robbed a pay train in Kansas. Unfortunately for Rudabaugh, this was an area protected by Bat Masterson. Before Rudabaugh’s gang had a chance to spend the rewards of others labors, they found themselves in jail. Being a man lacking in character, Rudabaugh turned states evidence against his comrades and gained his freedom.

During the summer of 1880 Rudabaugh joined the gang of a New Mexico ruffian by the name of Billy the Kid. About 6 months later Rudabaugh and Billy the Kid ran into a posse led by Sheriff Pat Garrett. Rudabaugh was arrested, tried and sentenced to hang.

Facing a rope, Rudabaugh went underground. He dug a tunnel and high tailed it to Old Mexico.

For 5 years Dave Rudabaugh created all kinds of havoc in Mexico. Then, finally, this man who had lived in the shadow of other more famous men got his moment of glory. For on February 19, 1866 the local Mexican villagers fed up with Rudabaugh’s escapades, killed him. They then cut off his head, stuck it on a pole, placed the pole in the center of the village and had a fiesta. For once Dave Rudabaugh or at least part of Dave Rudabaugh was the center of attention.

May 7, 2017 | Categories: Old West Myth & Fact | Leave A Comment »

By the late 1880’s most Indians were living on reservations. The reservations were under tribal ownership, with a communal style of control and use. Since it was the custom of white people to desire individual ownership of land and since many people felt that land ownership promoted industriousness, it was decided that the tribal ownership concept should be changed.

So, on February 8, 1887, the Dawes Severalty Act was passed. It gave the government the power to divide Indian reservations into privately owned plots. Men with families would receive 160 acres, single adult men got 60 acres, and boys received 40 acres. Women received nothing.

Except for women receiving nothing, it sounds like a pretty good deal, right? There were two problems. First, Indian culture was such that land, like air and sunlight wasn’t something that individuals owned. But the even greater problem was that it was a thinly veiled attempt by the government to take reservation land out of the hands of the Indians. For once the allotments were divided among the eligible Indians there were 86 million acres of land, or 62 percent of their holdings, left over. This land was available to be sold to anyone.

Even though friends of the Indians supported the act, it never produced the desired effect of assimilating Indians into white culture. In addition to the loss of lands, the Indians lost tribal bargaining power, and resentment developed that the government was trying to destroy traditional cultures.

Few people felt the Severalty Act was accomplishing its purpose, but it continued as law for forty years. Finally, in 1934, the Wheeler-Howard Act was passed that ended further transfer of lands from Indian hands, and made possible communal ownership to any tribe desiring it.

April 7, 2017 | Categories: Old West Myth & Fact | Leave A Comment »

In 1826 Stephen Austin authorized a force of men to fight Indians. This group was the inspiration that inspired the Texas Legislature to form the Texas Rangers on November 24, 1835. They were formed, not as a law enforcement group, but to protect the Texas frontier from Comanche Indians and Mexican banditos crossing over the border. Why are they called Rangers? They were called Rangers because their job was to “range” over wide areas.

In 1826 Stephen Austin authorized a force of men to fight Indians. This group was the inspiration that inspired the Texas Legislature to form the Texas Rangers on November 24, 1835. They were formed, not as a law enforcement group, but to protect the Texas frontier from Comanche Indians and Mexican banditos crossing over the border. Why are they called Rangers? They were called Rangers because their job was to “range” over wide areas. Moses Embree Milner was a well-built man, more than 6 feet in height. Not only did he constantly smoke a pipe, he chewed tobacco at the same time. In 1849, at the age of 20, he went to California like everyone else… for gold. Then he moved up to Oregon, and then to Montana where he acquired the name California Joe.

Moses Embree Milner was a well-built man, more than 6 feet in height. Not only did he constantly smoke a pipe, he chewed tobacco at the same time. In 1849, at the age of 20, he went to California like everyone else… for gold. Then he moved up to Oregon, and then to Montana where he acquired the name California Joe. Answer: There were several things people on the frontier did to make the hot, dry summers more bearable. In some cases they used ingenuity. In others it came with the territory. One that came with the territory was on the plains. With no lumber for homes, but plenty of territory or sod, they cut it into one foot by two foot rectangles and used the sod to make their homes. Although these “soddies” had a lot of drawbacks, they were warm in the winter and cool in the summer.

Answer: There were several things people on the frontier did to make the hot, dry summers more bearable. In some cases they used ingenuity. In others it came with the territory. One that came with the territory was on the plains. With no lumber for homes, but plenty of territory or sod, they cut it into one foot by two foot rectangles and used the sod to make their homes. Although these “soddies” had a lot of drawbacks, they were warm in the winter and cool in the summer. Clay Allison can be truly called a psychopath. At the height of the Civil War when the Confederate Army was drafting into service anyone who could hold a rifle, Clay was released on a medical discharge because he was maniacal.

Clay Allison can be truly called a psychopath. At the height of the Civil War when the Confederate Army was drafting into service anyone who could hold a rifle, Clay was released on a medical discharge because he was maniacal.

February 9, 1894, Chief, Red Cloud, Nebraska – Sing Sing Prison has a mysterious woman visitor, but that is not remarkable, because seven-eighths of the visitors to the convicts there are women. They all have burdens of sorrow to bear, but rarely of their own making, and they come and go year in and year out, to see beloved ones whom the world does not love and has put behind bars. The gray prison walls hold all that is dear in life to these mothers, wives, sweethearts and sisters.

February 9, 1894, Chief, Red Cloud, Nebraska – Sing Sing Prison has a mysterious woman visitor, but that is not remarkable, because seven-eighths of the visitors to the convicts there are women. They all have burdens of sorrow to bear, but rarely of their own making, and they come and go year in and year out, to see beloved ones whom the world does not love and has put behind bars. The gray prison walls hold all that is dear in life to these mothers, wives, sweethearts and sisters. It is said of Dave Mather that he spent as much time in jail as he did in the occupation of putting others there. Dave is known as “Mysterious” Dave Mather, because, supposedly little is really known about his life. But we know enough that if he notched his pistol each time he assisted in sending someone to their reward, he would have had to carry a couple of guns.

It is said of Dave Mather that he spent as much time in jail as he did in the occupation of putting others there. Dave is known as “Mysterious” Dave Mather, because, supposedly little is really known about his life. But we know enough that if he notched his pistol each time he assisted in sending someone to their reward, he would have had to carry a couple of guns.  This is an interview by Henry M. Stanley, African explorer who uttered the famous line “Dr. Livingston, I presume?” He met James Hickok while working for the Weekly Missouri Democrat. At the time of his interview with Wild Bill Hickok he was a scout for the Seventh Calvary.

This is an interview by Henry M. Stanley, African explorer who uttered the famous line “Dr. Livingston, I presume?” He met James Hickok while working for the Weekly Missouri Democrat. At the time of his interview with Wild Bill Hickok he was a scout for the Seventh Calvary.

The stories of the bravery of the Texas Rangers are legendary. However, there was one incident when a group of them were cowards. It was when events made the Texas Rangers surrender.

The stories of the bravery of the Texas Rangers are legendary. However, there was one incident when a group of them were cowards. It was when events made the Texas Rangers surrender.

May 9, 1885, Arizona Champion, Phoenix, Arizona – The Kansas City Journal tells of a game of poker played recently in that city between a Texan and Major Drumm. The Texan had no money, but plenty of cattle and an immense desire to play poker with the Major. The latter is known around the stock yards for his great natural resources, and he swept away the seemingly insurmountable difficulty by proposing a game of one steer ante, two steers come in and no limit. They played poker for cattle on this basis.

May 9, 1885, Arizona Champion, Phoenix, Arizona – The Kansas City Journal tells of a game of poker played recently in that city between a Texan and Major Drumm. The Texan had no money, but plenty of cattle and an immense desire to play poker with the Major. The latter is known around the stock yards for his great natural resources, and he swept away the seemingly insurmountable difficulty by proposing a game of one steer ante, two steers come in and no limit. They played poker for cattle on this basis.

In the 1860’s when a pioneer family headed out west, they usually did it in a covered wagon pulled by horses or oxen. One man, Samuel Peppard, didn’t have horses or oxen, but that didn’t stop him. His idea was a Wind Wagon.

In the 1860’s when a pioneer family headed out west, they usually did it in a covered wagon pulled by horses or oxen. One man, Samuel Peppard, didn’t have horses or oxen, but that didn’t stop him. His idea was a Wind Wagon. Temple Houston was the son of Texas’ founding father Sam Houston. He was an independent young cuss… so independent that at the age of 13, as a rawboned boy with shoulder length hair, he became a cowboy on a cattle drive from Texas to Montana.

Temple Houston was the son of Texas’ founding father Sam Houston. He was an independent young cuss… so independent that at the age of 13, as a rawboned boy with shoulder length hair, he became a cowboy on a cattle drive from Texas to Montana.

In the fall of 1892 Bill Doolin formed the Doolin gang that robbed trains and banks. He caused enough havoc to rile up the law in the area.

In the fall of 1892 Bill Doolin formed the Doolin gang that robbed trains and banks. He caused enough havoc to rile up the law in the area.  Simone Jules was a young French girl who arrived in Northern California at the height of the gold rush. For about four years she worked as a soiled dove in San Francisco’s Bella Union. Accumulating enough money to open her own place, she headed up to Nevada City, California, changed her name to Eleanor Dumont and opened the Dumont Palace gambling saloon.

Simone Jules was a young French girl who arrived in Northern California at the height of the gold rush. For about four years she worked as a soiled dove in San Francisco’s Bella Union. Accumulating enough money to open her own place, she headed up to Nevada City, California, changed her name to Eleanor Dumont and opened the Dumont Palace gambling saloon.  In 1850 over 9,000 miles of track covered the Northeastern portions of the United States. By 1860 there were 30,000 miles, more than the rest of the world combined, and the tracks were extending to the Midwest.

In 1850 over 9,000 miles of track covered the Northeastern portions of the United States. By 1860 there were 30,000 miles, more than the rest of the world combined, and the tracks were extending to the Midwest.

Dave Rudabaugh was born in Missouri in 1841. Early in life he moved to Kansas. At the age of 18, Dave started a gang that rounded up and sold other people’s cattle. By the age of 29 he and his gang moved on to robbing payroll trains and railroad construction camps.

Dave Rudabaugh was born in Missouri in 1841. Early in life he moved to Kansas. At the age of 18, Dave started a gang that rounded up and sold other people’s cattle. By the age of 29 he and his gang moved on to robbing payroll trains and railroad construction camps. By the late 1880’s most Indians were living on reservations. The reservations were under tribal ownership, with a communal style of control and use. Since it was the custom of white people to desire individual ownership of land and since many people felt that land ownership promoted industriousness, it was decided that the tribal ownership concept should be changed.

By the late 1880’s most Indians were living on reservations. The reservations were under tribal ownership, with a communal style of control and use. Since it was the custom of white people to desire individual ownership of land and since many people felt that land ownership promoted industriousness, it was decided that the tribal ownership concept should be changed.