TETON JACKSON

Many people spend their lives doing something they hate. On the other hand, when a person finds something he loves, and d oes it well, even if it is stealing horses, he’s lucky.

oes it well, even if it is stealing horses, he’s lucky.

Harvey Gleason was over six feet tall. He had a shabby beard, ruddy face with flaming red hair and black eyes. By his mid 40s, he had supposedly killed several soldiers and deputy marshals.

But, people didn’t know him as Harvey Gleason, everyone knew his as Teton Jackson. He got his name from his favorite area in Wyoming, the Teton Mountains and Jackson Hole. For a living Teton Jackson stole horses. Not one or two at a time, but hundreds. For about eight years, Teton and his men stole horsed during the summer and hid out among the Teton Mountains during the winter.

While in Eagle Rock, Idaho, Teton killed a man. When the sheriff came to investigate the shooting, he found the victim frozen stiff on the ground. Needing evidence of the killing, and unable to transport the whole body, the sheriff brought in just the head. An investigation found the killing to be justified.

Finally, tired of loosing horses, livestock associations in Idaho and Wyoming started putting up rewards for Teton and his men. And, money talked. A local sheriff found Teton, and brought him in. He was tried and on November 5, 1885, sentenced to 14 years in prison. Everyone breathed a sigh of relief. But, relief was short lived. For nine months later, Teton escaped from jail. Even though Teton was free for two years before he was recaptured, few horses were stolen because his gang’s numbers were drastically reduced by posse bullets and jail.

After four more years in jail, Teton received a pardon for good behavior. And he continued that good behavior for the next 35 years, marring a Shoshone woman, and doing some guiding, always riding a horse with his brand on it.

OLIVER LOVING

On September 25, 1867, Oliver Loving, one of the great pioneer Texas cattlemen, died at the age of 55. Incidentally, the story of his de ath may have a familiar ring.

ath may have a familiar ring.

Oliver Loving was born in Kentucky, and moved to Texas at the age of 33 where he engaged in farming and freighting. And finally, at the age of 44, when most men are choosing a quiet life, Loving got involved with cattle, and driving them to places where they had never been.

In 1858 he took Texas longhorns to Chicago along what was to be later known as the Shawnee Trail. About a year later he took cattle up to Denver to supply the needs of the gold miners.

Following the Civil War, Oliver Loving teamed up with Charles Goodnight and in 1866 they established the Goodnight-Loving Trail that went from Texas to Fort Sumner, New Mexico.

The second year they took the trail they encountered a number of Indians, causing delays in the drive. To assure the buyers that the cattle were on the way, Loving and Billy Wilson went in advance of the cattle to Fort Sumner. Along the way they encountered some Indians. And in a skirmish Loving was shot in the wrist and side.

Thinking he was going to die, Loving persuaded Wilson to leave him. But Loving didn’t die. For seven days he crawled, without food, until he encountered some men who took him to Fort Sumner. Gangrene had set in his arm, but an inexperienced doctor chose not to amputate.

When partner Charles Goodnight arrived in Fort Sumner, he was excited to discover Loving had survived. But the news was not good. The gangrene had gotten so bad that even after amputation, Loving died three weeks later.

If the story of Loving’s death sounds a bit familiar, it’s probable because you’ve watched the movie Lonesome Dove, and remember the character, Gus McCall, said to have been patterned after Loving.

MEAT PACKING CAPITAL

Today Chicago, Illinois is considered the meat packing capital of the United States. But that title was supposed to have gone t o another town.

o another town.

In the late 1860’s Texas cattlemen were having a problem with a disease called Texas fever. It didn’t affect the Texas Longhorns. But northern cattle, exposed to ticks from the Longhorns, were adversely affected. Because of this, cattle drives were not allowed to travel through Colorado, Nebraska, Kansas, Missouri, Illinois and Kentucky which basically cut them off from Northern markets.

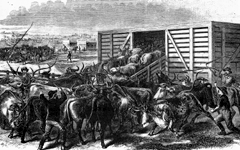

A young man named Joseph McCoy got the idea to transport the Texas Longhorns through the quarantine states on trains. He selected the remote town of Abilene, Kansas as the starting point.

Then he chose St. Louis, Missouri as the destination point. This was the headquarters of the Missouri-Pacific Railroad. So, at the age of 19, he presented his idea to the President of the railroad.

The railroad President said, “It occurs to me that you haven’t any cattle to ship and never did have any, and I, sir, have no evidence that you ever will have. Therefore you get out of this office, and let me not be troubled with any more of your style.”

McCoy found a warmer reception from the St. Jo. Railroad that ended in Chicago. Starting on September 5, 1867, almost 1,000 carloads of cattle were shipped from Abilene to Chicago. The next year 75,000 cattle were shipped.

Realizing his mistake the Missouri-Pacific President, who had rejected McCoy’s proposal, tried to solicit his business. Joseph McCoy told him, “It occurs to me that I have no cattle for your railroad, never have had and there is no evidence that I ever will have.”

MASS LYNCHING

In the predawn darkness of August 28, 1885, nine men were lynched. The local newspaper didn’t report it. Residents didn’t talk about it. And, even today little is said about it. But, we’re going to talk about it.

The year was 1885. With the Atlantic and Pacific Railroad, passing through the town, Flagstaff, Arizona was booming. As well as families, soiled doves, gamblers and hard cases arrived. A section of town called Whiskey Row had saloons that were open round the clock. And, there were as many as a dozen robberies each night. The nearest law was in Prescott, Arizona, some 87 miles away.

When the local paper wrote articles condemning the bad element, they threatened to burn down the town. Six local businessmen met in secret to discuss a solution to the problem. In order to discover the troublemakers, one of the men volu nteered to cruse Whiskey Row with a pocket of gold coins. After four nights, the men had accumulated quite a list.

nteered to cruse Whiskey Row with a pocket of gold coins. After four nights, the men had accumulated quite a list.

In the middle of August an ultimatum was tacked on the door of every saloon. It read: “Notice – Tinhorns have 24 hours left.” A few left town. But many stayed.

The names of the remaining tinhorns were put in a hat, and the morning of August 28, 1885 ten names were drawn out. Quietly, nine of the ten were found; hands tied; and all nine men were hanged. That morning citizens were whispering about men hanging from a tree outside town.

After about 24 hours the men were cut down and buried. No one spoke of it openly. Nothing was ever written about it in the newspaper. The sheriff arrived from Prescott, and returned empty handed, because no one knew anything about a lynching. Life went on as if nothing had happened. Except for one thing, that is. All the tinhorns decided Flagstaff, Arizona wasn’t that exciting a place to live.

CLAY ALLISON

Clay Allison was a hard-drinking, prankster of the type who becomes a legend in his own time. During his lifetime, Allison only killed four people. But the stories about him that didn’t involve killing are as entertaini ng as those that did.

ng as those that did.

There’s the story of Clay Allison looking up gunman Mace Bowman with the object of killing him. But, Bowman was a congenial person, and the two men ended up getting drunk together. Still curious about who was the fastest, they decided to test each other’s speed with some fast draws. Allison found that Bowman was faster than he was. So, Allison suggested they strip to underwear, and shoot at each other’s bare feet to see who could move faster. They were either poor shots or fleet of feet, because a short time later the two men, out of breath, bellied up to the bar for another drink.

Then, there was the time on August 15, 1874, when Allison arrived in Cheyenne, Wyoming with a raging toothache. Now, Cheyenne had two dentists. So, Allison chose the closest one and climbed in his chair. Unfortunately the dentist drilled the wrong tooth. When the dentist announced his mistake, Allison angrily jumped out of the chair, and went over to the other dentist’s office. The other dentist took care of the problem.

With his pain gone, Allison returned to the first dentist, and pinned the dentist in his chair. Grabbing the dentist’s forceps, and proceeded to pull, according to different stories, one, three or all of the dentist’s teeth. I can assure you that dentist never drilled on the wrong tooth again.

THE BUCK GANG

There was a gang in the Old West lasted only thirteen days. But during those thirteen days, they cut a swath of carnage that no other gang could match.

There was a gang in the Old West lasted only thirteen days. But during those thirteen days, they cut a swath of carnage that no other gang could match.

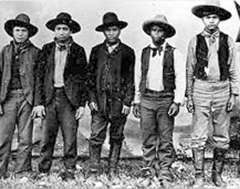

Rufus Buck was a Ute Indian living in the Indian Territory. His gang comprised of four Creek Indians and a combination Creek and black. All of them had served time in jail for minor offences.

Buck supposedly boasted, “that his outfit would make a record that would sweep all the other gangs of the territory into insignificance.” And on July 28, 1895, the gang started a thirteen-day crime spree that did exactly that.

They killed Deputy Marshal John Garrett. They came across a Mrs. Wilson. She was kidnapped and violated. From there they saw Gus Chambers with some horses. When he resisted, the Buck Gang killed him. They next robbed a stockman, taking his clothes and boots. Fortunately, he was able to escape in a hail of bullets. Two days later, they invaded the home of Rosetta Hassan. She was violated in front of her husband and children.

The gang was arrested, and brought before Hanging Judge Isaac Parker, and they were sentenced to be hanged. He scheduled it for July 1, 1896 between nine in the morning and five in the evening.

Quite possibly Judge Parker should have stated an exact time, because, on the day of the hanging, one of the gang members said he wanted to be hanged at ten in the morning so his body could be on the 11:30 train. Rufus Buck protested, saying that if he was hanged that early, there would be a several hour delay before his body could be on the appropriate train. The Rufus Gang then decided they wanted to be hanged separately.

Marshal Crump smiled, set the time for 1:00, and hanged them all at one time.

ELLA WATSON HANGED

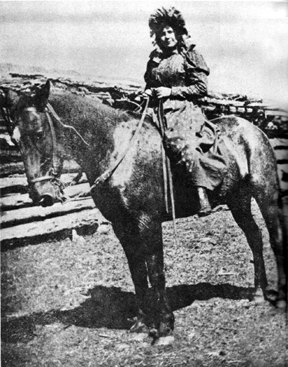

On July 20, 1889 the first woman in Wyoming, either legally or illegally, was hanged. I think you’ll find her story very interesting.

Ella Watson has been described as “a dare devil in the saddle, handy with a six shooter and adept with the lariat and branding iron.” She has also been described as a homely prostitute who happened to take the wrong form of payment for her services.

In truth she was homely. Ella Watson secretly married a Wyoming Territory merchant named Jim Averill. Jim wasn’t liked by the cattle ranchers. That’s because Jim had acquired land traditionally used for grazing, and he rubbed salt in the wound by writing “anti-cattlemen” letters to the local paper.

Ella filed for a homestead, and built a log cabin close to Jim Averill’s store where she started plying her trade as a soiled dove. She also started taking cattle as payment for her services.

The cattle ranchers accused Jim and Ella of cattle rustling. Now, quite possibly a cowboy or two may have paid her with cattle not belonging to him…but because the local authorities wouldn’t take action against them, the cattlemen kidnapped Jim and Ella and lynched them.

It was well known who did the lynching. There were even five witnesses. But they were all either shot or disappeared. So the trial never took place.

Now, most people have never heard of Ella Watson, because after her death she acquired another name.

The town’s people started protesting the lynching. So the cattlemen planted stories in local newspapers changing the homely prostitute Ella Watson into a gun slinging gang leader by the name of “Cattle Kate”. She became so famous her story was written-up in New York’s “Police Gazette.”

DODGE CITY, KANSAS

As the railroad headed west, towns grew up along side it. One of the more famous Western towns was named Buffalo City. However, that wasn’t the name under which it became famous.

It was the middle of July 1872 when the Atchison, Topeka and Santa Fe Railroad reached a peddler’s camp by the name of Buffalo City, Kansas, located about five miles from the military reservation of Fort Dodge. Almost overnight tent saloons and gambling dens sprang up. Within a matter of weeks it was a town of false-fronted buildings. And shortly afterward the Buffalo City town signs were taken down and replaced with signs reading, Dodge City, after the name of one of the town fathers, Colonel Richard I. Dodge.

Because it was against the law to sell liquor in unorganized regions of Kansas, the Dodge City residents petitioned to organize the county of Ford. Interestingly, the petition contained the names of as many transients and railroad people as residents. Even though it was challenged, the state legislature, out of expediency, approved Ford County

Dodge City started out as a hangout for buffalo hunters. Then when the cattle drives and cowboys started coming north, with twenty saloons, numerous dance halls and houses of ill repute, Dodge City became known as the “Queen of the Cow Towns.”

Over the next few years the likes of Wyatt Earp, Doc Holliday, Bat Masterson and Belle Starr took residence there. But, they only stayed there temporarily, because fame had other places to go and other events in which to participate.

Dodge City only had about 3,000 residents at the height of the population. By 1885, a little over 15 years after it became a town, the railhead had moved on to other towns. The Chisholm Trail was being plowed under by wheat farmers, and the law was maintaining order, so Dodge City settled down and became civilized.

OLD WEST 4TH OF JULY

Celebrating the independence of our country was important even in the Old West. And, as we shall see, people putting on the celebration in the 1800’s ran into the same problems as today.

In 1868 the Nevada mining camps of Hamilton and Treasure Hill comprised of a few hardy miners and even fewer women. However, it was decided that they would have a 4th of July celebration.

They formed the flag committee, the music committee and the dance committee. The music committee’s job was simple, yet complicated. There was only one man in town who had a musical instrument, a violin. The complication was that he tended to get drunk. So, they had to regulate the flow of whiskey to the musician.

The dance committee comprised of all the women in town…a total of two. Like volunteer committees sometimes do, the flag committee waited until the last minute to get a flag. And then it was to late to travel the 120 miles to the nearest store. So, good ol’ American ingenuity took place. They found a quilt with a red lining, and some white canvas material. A traveling family camped nearby had a blue veil. This was doubly good because the family included a mother and four girls…more women for the dance. But the girls didn’t have shoes, making it impossible to dance on the rough planked floor. So, a collection of brogan shoes was taken up among the miners.

On the 4th of July, a parade formed at Hamilton and with the makeshift American flag proceeded to Treasure Hill. Speeches were made. Sentiment ran high. They decided to form a new town called the White Pine Pioneers, and that the flag should go into the town’s archives. Unfortunately, the town disappeared and the flag ended up being used as a bed sheet.

SHANGHAI PIERCE

A friend said to me, “There aren’t any cowboys from Rhode Island.” I had to correct him by telling that there was a great cowboy who came from Rhode Island.

Abel He ad Pierce was born in Rhode Island on June 29, 1834. At the age of twenty he stowed away on a schooner and ended up in southern Texas. Abel took a job for a cattleman named Grimes. Starting out doing odd jobs, Abel worked his way up to trail boss, taking cattle to New Orleans.

ad Pierce was born in Rhode Island on June 29, 1834. At the age of twenty he stowed away on a schooner and ended up in southern Texas. Abel took a job for a cattleman named Grimes. Starting out doing odd jobs, Abel worked his way up to trail boss, taking cattle to New Orleans.

Abel Head Pierce was a 6 foot, 5 inch bearded giant of a man who had a habit of wearing spurs with extra large rowels, and strutting around town. Someone remarked that he looked like a Shanghai rooster, and he became Shanghai Pierce. Now, that’s a name any cowboy would be proud of.

After serving in the Civil War, Shanghai returned to Texas and started accumulating cattle. Shanghai went to Kansas for a couple of years…supposedly to let things cool down in Texas after lynching a couple of rustlers.

He ended up with a 250,000 acre ranch appropriately called the Rancho Grande. Obviously, he was a major factor in the Texas cattle industry.

Looking for cattle that would be resistant to ticks that caused problems with Texas cattle going north, and a breed that would produce more meat, Shanghai went to Europe and brought home some Brahma cattle, which he crossed with the Texas Longhorns.

By the end of the 19th century Shanghai Pierce’s Rancho Grande approached a million acres. When Shanghai felt his life was close to coming to an end he hired a San Antonio sculptor to make a larger than life statue of himself to be placed over his grave. Asked why, Shanghai responded, “I knew that if I didn’t do it, no one else would.”

TOM CUSTER

It is said of George Armstrong Custer that his officers fell into two categories: Those who hated him and those who were related to him… and five of them were related. This story is about one of those relations… his brother Tom.

Tom Custer was five years younger than George, and he spent his life in the shadow of his older brother. Although he wasn’t as flamboyant as George, Tom was his own man. For instance, unlike his brother, Tom liked his liquor.

spent his life in the shadow of his older brother. Although he wasn’t as flamboyant as George, Tom was his own man. For instance, unlike his brother, Tom liked his liquor.

In 1870, while camped with the Seventh Cavalry near Hays City, Kansas, where at the time Wild Bill Hickok was the marshal; Tom supposedly got drunk, and was chased out of town by Hickok. Tom vowed revenge. A short time later Hickok had a shootout with three troopers from the Seventh. It’s though that Tom Custer had something to do with the affair.

In 1874 Tom led an expedition into the Yellowstone River area and arrested a chief by the name of Rain-in-the-Face. Rain-in-the-Face later escaped, vowing to someday cut out Tom’s heart. Quite possibly Rain-in-the-Face got his wish for Toms body was so mutilated in the Little Big Horn battle that his initials, T. W. C., tattooed on his arm was the means of identification.

Although Tom never got the fame of his older brother, during the Civil War Tom’s exploits resulted in his accomplishing something no other soldier had done before him and few have accomplished since…Tom won two Congressional Medals of Honor…Tom Custer has been compared to Alvin York of World War I and Audie Murphy of World War II.

SAMUEL COLT’S 45

We’ve all read and heard that it was Samuel Colt’s 45 that tamed the West. Did you know that gun manufacturing wasn’t Colt’s first venture into business? And did you know that Samuel Colt was a failure at gun manufacturing before he was a success. To get the whole story copy and then paste the following link in your web browser:

We’ve all read and heard that it was Samuel Colt’s 45 that tamed the West. Did you know that gun manufacturing wasn’t Colt’s first venture into business? And did you know that Samuel Colt was a failure at gun manufacturing before he was a success. To get the whole story copy and then paste the following link in your web browser:

http://youtu.be/h9BHMhCKQtY

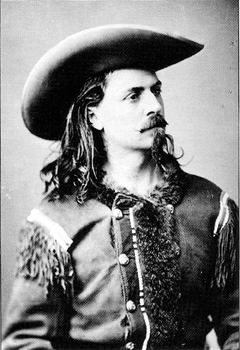

BUFFALO BILL’S METAL OF HONOR

Everybody knows about Buffalo Bill Cody. Here’s something about him that most people don’t know. And I’m sure it will surprise you.

Buffalo Bill C ody was the consummate showman. Anytime he had the opportunity to get publicity, he took it…even making up stories about himself, and embellishing those that actually happened. But there was one accomplishment that didn’t get much publicity. That was that Buffalo Bill Cody won the Congressional Metal of Honor. Part of the reason was that, he had it, and then he lost it, and then he got it back. I’ll explain.

ody was the consummate showman. Anytime he had the opportunity to get publicity, he took it…even making up stories about himself, and embellishing those that actually happened. But there was one accomplishment that didn’t get much publicity. That was that Buffalo Bill Cody won the Congressional Metal of Honor. Part of the reason was that, he had it, and then he lost it, and then he got it back. I’ll explain.

In May of 1872, with novels of his exploits in circulation, Cody was scouting for the 3rd Cavalry. He was guiding an advance unit of 6 men when, a mile away, Cody spotted the Indians they were pursuing. He led the soldiers to within 50 yards of the Indians before gunfire erupted. It wasn’t a major battle, but in the process Cody killed one Indian and the other men killed two others.

On the basis of the report that was written up about that encounter, on May 22, 1872, Buffalo Bill Cody was awarded the Congressional Metal of Honor. Right after this, Buffalo Bill quit his job as scout and started touring in the play The Scouts of the Plains.

But this wasn’t the end of the story of Buffalo Bill’s Metal of Honor. In 1916, just prior to his death, Congress took a look a the people who had received the Metal of Honor and rescinded Buffalo Bill’s along with 910 others. The reason given was that Buffalo Bill was a civilian employee at the time of his gallantry.

But, in the spirit of “all’s well that ends well,” in 1989, 72 years after his death Congress took another look, and restored Buffalo Bill’s Congressional Metal of Honor.

FRONTIER HOUSEKEEPING

Today one of the first things every newly married couple does, once the get back from their honeymoon, is to set up housekeeping. As we shall see, some 150 years ago, setting up housekeeping was a bit different.

Today one of the first things every newly married couple does, once the get back from their honeymoon, is to set up housekeeping. As we shall see, some 150 years ago, setting up housekeeping was a bit different.

Bethenia Owens and Lagrande Hill got married on May 15, 1854. She was fourteen years of age. Skipping any honeymoon, they immediately moved into their newly purchased home. It was a log cabin that was 12 feet by 14 feet in size.

The door was so low that a man had to stoop to go in and out. The cabin had neither floor nor chimney and wide cracks admitted both drafts and vermin…which included snakes and lizards.

Their furniture consisted of a pioneer bed, made by boring three holes in the logs of the wall in one corner, in which to drive the rails. That way the bed required only one leg. The table was a rough shelf, fastened to the wall. The cupboard was three shelves on the wall.

Her dishes were tin ware. The cooking utensils comprised of a pot, tea-kittle, frying-pan and coffee-pot. In addition Bethenia had a butter churn, a wash tub and board, twenty gallon iron pot for washing purposes, water bucket and tin dipper.

Her father gave her money to buy groceries, which she did the afternoon of her wedding. Her mother contributed a good straw bed, pillows and blankets.

Bethenia considered this a most excellent start in life.

Unfortunately, this marriage that started out so excellently didn’t end that way. Bethenia’s husband beat her, and at the age of eighteen she left him. What did she do then? She went back to her parent’s home, learned to read and write, went to school and ended up becoming the first woman physician in the West.

WIND WAGON

In the 1860’s when a pioneer family headed out west, they usually did it in a covered wagon pulled by horses or oxen. One man, Samuel Peppard, didn’t have horses or oxen, but that didn’t stop him.

In the 1860’s when a pioneer family headed out west, they usually did it in a covered wagon pulled by horses or oxen. One man, Samuel Peppard, didn’t have horses or oxen, but that didn’t stop him.

On May 9, 1860 Samuel Peppard headed out west. This was during the time of the Pike’s Peak gold rush, and Samuel wanted to do some gold prospecting. He didn’t have any horses or oxen, and he didn’t want the obligation and expense of taking care of them.

But, he did live in the Kansas Territory. And anyone who has been through Kansas knows it’s pretty flat, and the wind tends to blow rather strongly. Being a creative person, Peppard decided to take advantage of the resources at hand, and so he designed the world’s first wind-sailor. Built like a small boat, it was about 8’ long and 3’ wide, and it had four large wagon wheels. Weighing about 350 pounds, it was designed to hold 4 people.

The first time out, the wind blew the wagon over. So Peppard reconstructed the sails, rudder and brakes. By now everyone called it “Peppard’s Folly”.

With three of his friends aboard, Peppard raised the sails, and “Peppard’s Folly” took off across the prairie. Depending on the strength of the wind, it got up to 30 miles per hour.

On days when there was no wind, Peppard and his three friends just sat back, smoked a cigarette, and swapped stories.

They traveled about 500 miles before a dust devil came along and turned the wind wagon into a pile of rubble.

Peppard and his friends finally made it to Denver, but like most seekers of gold, they didn’t find anything.

Peppard later went back to Kansas, and lived to the ripe old age of 82. But he was always known as the guy who sailed to Denver.

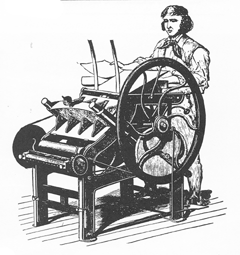

NEWSPAPER BATTLE

Being first wasn’t always important in the Old West. But, it made all the difference in one race. And, the objects of the race didn’t even move an inch.

In 1859 the Pikes Peak Gold Rush was a bust. The settlements of Cherry Creek, Montana City and Denver City were on the verge of becoming ghost towns when another gold vein was discovered, and people came running.

John Merrick decided the area needed a newspaper. He bought an old press and headed to Cherry Creek. Not seeing any reason for haste, Merrick took his time putting his newspaper together.

But, four days after Merrick had arrived; William Byers arrived from Omaha, Nebraska also with a printing press and the same idea. Byers immediately located an office in the best building in town. It happened to be an attic of a tavern, and the roof leaked so bad a canvas had to be hung over the press to keep it dry.

A race was on. Bets were placed, and everyone cheered on their favorite editor. Finally, on Saturday evening, April 23, 1859, William Byers’ Rocky Mountain News hit the streets just twenty minutes before the first copy of John Merrick’s Cherry Creek Pioneer. In the news industry, a scoop of twenty minutes is like a lifetime. So, John Merrick sold out and left for the gold fields.

William Byers had the area to himself. However, his troubles weren’t over. There was a battle between the two neighboring towns on either side of Cherry Creek. So Byers couldn’t be accused of favoritism, he moved his equipment to a building that was virtually astride Cherry Creek. Not a good move. Four years after he started his newspaper, the area flooded, and washed away the building. His press wasn’t found until 35 years later.

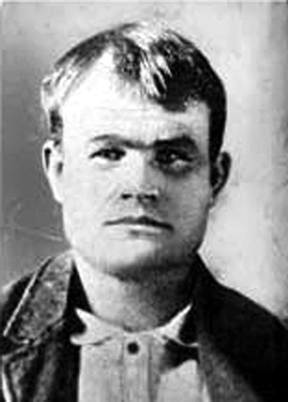

BOB PARKER

On April 13, 1866 the Old West’s least likely looking and acting head of a bandit gang was born in Utah. His name was Robert Leroy Parker.

Bob Parker spent his childhood near Circleville, Utah, a hangout for outlaws. As a young person Bob Parker befriended an outlaw by the name of Mike Cassidy. Mike Cassidy taught Bob how to shoot. He also took Bob with him on some of his cattle rustling ventures.

Bob Parker, along with Mike Cassidy, stole a few horses, robbed a bank or two and created general havoc in a small way. Bob also had some legitimate jobs. He worked for a short while as a butcher in Rock Springs, Wyoming.

As Robert Leroy Parker started getting into trouble he assumed an alias, in part to make him sound meaner, and to save his family embarrassment. His last name came from his early friend, Mike Cassidy. His picked up his first name while a butcher in Rock Springs.

Butch Cassidy, and his partner the Sundance Kid, also an alias – the result of his spending time in a jail in Sundance, Wyoming – were lost in history until a movie starring Paul Newman and Robert Redford was released.

Although the real Butch Cassidy didn’t look anything like Paul Newman, he had the same “happy-go-lucky” attitude that Paul Newman portrayed. Although he was 5’9” tall, and was known for clowning around, he had the ability to rule a gang of bad desperados known as “the wild bunch.”

The biggest controversy concerning Butch Cassidy was portrayed at the end of the Newman – Redford movie. Although tradition says that Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid died in Bolivia, Robert Leroy Parker’s family maintains he returned to the United States, purchased a ranch, and searched for the loot he and the wild bunch had stashed until he died in 1937.

RICHARDSON/LOVING GUNFIGHT

Gunfights in the Old West were usually caused by one of three reasons…women, gambling and revenge. As we shall see, one of Dodge City’s most famous gunfights was over a woman.

Gunfights in the Old West were usually caused by one of three reasons…women, gambling and revenge. As we shall see, one of Dodge City’s most famous gunfights was over a woman.

Levi Richardson was a buffalo hunter who, because of the lack of buffalo, had become a freighter. He was a well-liked, hard working individual who was known for his proficiency with a pistol and rifle…As well as having a quick temper.

Frank Loving, also known as “Cock-eyed” Frank because his eyes tended to look toward each other, was an ex-cowboy turned gambler. Loving, unlike Richardson, was known to be cool, with a steady nerve. Both men were spending some time in Dodge City, Kansas.

Now comes the catalyst…a woman. It seems that Levi Richardson fell in love with a young woman. Unfortunately, for him, she loved another. And, that person was none other than Cock-eyed Frank Loving.

It was about 8:00 Saturday evening, April 5, 1879. Richardson was warming himself at the potbelly stove in the Long Branch Saloon, when Loving came in and took a seat at one of the gambling tables. Richardson followed him to the table. A few, less than genteel, words were exchanged. With both men standing face to face, Richardson went for his gun. He pulled off a shot as Loving was drawing his pistol. Loving’s first shot misfired. Seeking cover, Loving ran behind the potbelly stove. But Richardson was right behind him taking two more shots.

Fortunately, for Loving, after that first misfire, his gun performed flawlessly. Using cool deliberation, Loving shot Richardson in the chest, side and arm. He died on the spot. Loving, on the other hand, suffered only a scratch on the hand. After the smoke settled, both guns were checked. In the fracas, both men had empted them. The amazing thing about the gunfight was that with led flying everywhere in a crowded room, no bystander was hit.

If you want to learn about more gunfights as they really happened go to www.ChronicleoftheOldWest.com and check out Dakota’s gunfight CD.

SOCKLESS JERRY SIMPSON

Any baseball fan knows of Shoeless Joe Jackson. Do you know about a politician who in the 1890’s was known as “Sockles s” Jerry Simpson?

s” Jerry Simpson?

In the early 1890’s the United States was going through an economic downturn. The western farmers were unset over low crop prices, high shipping costs and even higher interest rates. They began forming groups like the Grangers and the Farmer’s Alliances to give mutual assistance. And finally, angered that the major political parties weren’t doing anything to help the plight of the farmer…these groups became the nucleus of the formation of a third party, called the Populists.

One of the farmers having a tough time was a man named Jerry Simpson. As a southwest Kansas rancher, Jerry knew the challenges of making a living by toiling the land. Hoping to be able to get help for the farmers, Jerry became involved in Republican politics. But becoming upset with their lack of action, he quickly became one of the most influential members of the Populist Party.

On March 30, 1891, Jerry declared his candidacy for the U. S. Congress on the Populist ticket. His opponents tried to label him as a backwoods hick who didn’t even wear socks. Jerry knew how to make lemonade out of lemons. And he quickly turned the insult into his advantage. He proudly started calling himself “Sockless Jerry”, the sockless Socrates of the plains. And it worked too. He not only was elected once, he was elected three times to Congress. As a matter of fact, had he not been born in Canada, and ineligible to become President, he would have been the Populist’s candidate for our highest office.

As with most third party movements in the United States, the Populist Party was short-lived. But during its life, it was able inspire the major parties to look at some more progressive ideas, such as the regulation of the railroads.

WOMEN JURORS

With lawlessness and corruption rampant in Laramie, Wyoming in 1870, and even vigilantism ineffective, something had to be done. An outlaw would be caught in the midst of a crime, and then declared not guilty by a jury of men who were hed ging their bet should they end up a defendant.

ging their bet should they end up a defendant.

Something had to be done. And, that something was to select women for jury duty. The judge didn’t just select a couple of women as token representatives; he made the grand jury half women.

This was not only the first time a woman served as a jurist in Wyoming, it was the first time in the United States. The national press came down hard on them. Men were heard to say that if their wife served on a jury, they would no longer live with them.

To protect their identity, the women wore veils. A female bailiff was appointed to spend the night outside the rooms where they were housed.

Women were thought to be incapable of serving on a jury because they were too emotional and too easily swayed. Those opposed to women’s rights thought the jurors would fail, thus ending the Suffrage Movement.

But, they were wrong. The jury handed down indictments for murder, horse and cattle stealing and illegal branding. When the jury retired to decide a murder case, initially all of the women were for conviction, but only half of the men. When the verdict was handed down, the man was convicted.

Afterward, the judge said the women served with dignity and intelligence, as well as being firm and resolute. He also noted that two days after the grand jury had begun, a number of unsavory characters had left town.

CHINESE EXCLUSION ACT

Famine and political instability in the 1850’s made it difficult for Chinese citizens. Adding to this burden was the Chinese tradition  of men taking care of their extended families.

of men taking care of their extended families.

Gold had been discovered in California and reports of easy wealth reached China. So, thousands of men made arrangements to come to California. The plan was to work the gold fields, accumulate a sizeable wealth, and return to China. But, in order to get passage, they borrowed from wealthy Chinese or Anglos. Thus becoming indentured to them until the passage had been paid off. Unfortunately, the Chinese were paid just enough to keep their hopes alive, but not enough to pay off their debt.

By 1880 over 100,000 Chinese lived in the United States, with most of them in California. Laws prevented Chinese from owning mines. So those Chinese who were free found a variety of ways to earn a living. Groups of them would go to abandoned claims and work the slag piles left behind by gold miners…and many became wealthy this way.

Others opened laundries and restaurants, considered “women’s work” by most Anglo men.

With the Chinese being treated with a growing resentment, the government responded by limiting Chinese immigration with the Chinese Exclusion Act. But, only laborers were excluded. Professionals and merchants who supported our trade with China were allowed in. Six years later, on March 12, 1888, the Chinese government officially supported the principals of the Exclusion Act by not allowing any laborers to immigrate to the United States.

It’s interesting to note that the Chinese Exclusion Act remained the law of the land until 1943 when China became our ally during World War II.

SEQUOYAH

Anyone who has visited the coast of Northern California has marveled over the giant redwood trees called Sequoias. Have you ever w ondered where their name came from?

ondered where their name came from?

It comes from the name of a Cherokee Indian born in 1760 in Tennessee. As a young man he was a metal craftsman, making silver jewelry. While fighting on the American side in the War of 1812, he became intrigued with what he called “talking leaves,” or words on paper. Although Sequohah had no formal education, he comprehended the basic nature of the symbolic representation of sounds.

In 1809 he began working on a Cherokee written language. At first he tried picture symbols, but found them impractical. Looking at English, Greek and Hebrew, he developed 86 characters that would express the various sounds in the Cherokee language. It was so simple that it could be mastered in less than a week.

In 1821 he submitted his new written language to the Cherokee leaders. As a demonstration Sequohah wrote a message to his six-year-old daughter. She read the message and responded in kind. The tribal council immediately adopted the system.

The Cherokee were divided into two groups, Sequohah’s in Georgia and Tennessee, and the western Cherokee in Oklahoma. In 1822 Sequohah went to Oklahoma, and taught the alphabet to the Cherokee there.

Finally, on February 21, 1828 a printing press with Cherokee type was developed. Within months, the first Indian language newspaper appeared, called the Cherokee Phoenix.

While in Mexico teaching the Cherokee language, he became ill with dysentery, and died. Although the spelling is a bit different, the giant Sequoias stand as monuments to the man who developed the Cherokee alphabet.

KILLING A WOMAN

One of the codes of the Old West was that women were not to be hurt. In an incident that took place n ear Yuma, Arizona on February 7, 1901, that code was broken.

ear Yuma, Arizona on February 7, 1901, that code was broken.

The ownership of a ranch occupied by Joseph and Mary Burns was under dispute. Constable Marian Alexander went to the ranch to serve papers on the Burns. With Joseph Burns away, Mary Burns met Constable Alexander with a rifle. Unarmed and unprepared for a confrontation, Alexander left.

Alexander returned with two other men and a shotgun. Mrs. Burns still had her rifle. The two men stayed on their horses while Constable Alexander walked over to Mary Burns. An argument ensued, and Alexander pulled the triggers on both barrels…killing Mary Burns.

The news spread across the area like wildfire. Constable Alexander surrendered, and was placed in the Yuma Territorial Prison…more for his protection. The papers editorialized that “the jail was not deemed strong enough to save the murderer from the anger of the citizens.”

Mary Burns’ brother Frank King, and father, Samuel King, arrived in town. Alexander and the other two men were indicted by a grand jury, which, incidentally contained Samuel King, Mary Burns’ father. Alexander was sentenced to life in prison.

As Alexander was leaving the courthouse in the company of police, a sniper fatally shot him. The police hurried to the shooter’s location, and found both Frank and Samuel King nearby. Neither was armed, and no one identified them as the shooter, they were released.

For years, a rumor circulated that after the shooting of Alexander, a rifle belonging to Samuel King was found in a nearby bale of hay, but in the spirit of frontier justice, it disappeared.

THE DALTON BROTHERS

Ma and Pa Dalton had t en sons. Most of them grew up to be law-abiding citizens. One of the brothers, Frank, was killed while serving as a deputy for “Hanging Judge” Isaac Parker. Following their brother’s example, Grat, Bob and Emmett worked as lawmen in the Oklahoma Territory. But, they spent their spare time rustling cattle, and accepting bribes from whiskey smugglers. Although they managed to escape prosecution, by 1890 they were discredited as lawmen.

en sons. Most of them grew up to be law-abiding citizens. One of the brothers, Frank, was killed while serving as a deputy for “Hanging Judge” Isaac Parker. Following their brother’s example, Grat, Bob and Emmett worked as lawmen in the Oklahoma Territory. But, they spent their spare time rustling cattle, and accepting bribes from whiskey smugglers. Although they managed to escape prosecution, by 1890 they were discredited as lawmen.

Deciding it was time for the Daltons to engage in some serious crime, Bob and Grat headed for California where they met up with their brother Bill. On February 6, 1891 Bob, Grat and Bill decided to rob a train. A little north of Bakersfield, they managed to flag down a Southern Pacific train traveling from San Francisco to Los Angeles.

While Bill kept the passengers occupied by shooting over their heads, Bob and Grat asked the engineer to show them the location of the express car. But the engineer refused, and he tried to escape. One shot from a Dalton pistol stopped the engineer in his tracks.

Bob and Grat found the express car on their own. They demanded the guard open the express car door. But he refused. And not only that, he started shooting at them from a small spy hole.

Totally frustrated, the Daltons rode away empty handed. Now, after the fiasco of their first major attempt at outlawry, the average person would probably decide that maybe the outlaw trail was not for them. But the Daltons weren’t average. And they kept it up, until a year and a half later when they decided to rob two banks in Coffeyville, Kansas, and the Dalton gang was wiped out.

I guess sometimes when a person fails they shouldn’t try try again.