SHE FREQUENTLY VISITS SING SING PRISON.

A Mysterious Woman Whose Repeated Visits

to the Famous Penal Institution Have

Excited Interest as to Her Identity.

February 9, 1894, Chief, Red Cloud, Nebraska – Sing Sing Prison has a mysterious woman visitor, but that is not remarkable, because seven-eighths of the visitors to the convicts there are women. They all have burdens of sorrow to bear, but rarely of their own making, and they come and go year in and year out, to see beloved ones whom the world does not love and has put behind bars. The gray prison walls hold all that is dear in life to these mothers, wives, sweethearts and sisters.

February 9, 1894, Chief, Red Cloud, Nebraska – Sing Sing Prison has a mysterious woman visitor, but that is not remarkable, because seven-eighths of the visitors to the convicts there are women. They all have burdens of sorrow to bear, but rarely of their own making, and they come and go year in and year out, to see beloved ones whom the world does not love and has put behind bars. The gray prison walls hold all that is dear in life to these mothers, wives, sweethearts and sisters.

The husband who has committed crime that his wife may have luxurious surroundings usually retains the affections of that wife, even when he dons stripes and is close cropped. The professional burglar often is a model family man and does not sever his family ties when he “does time.” The man who kills his fellow man for the affections of a woman and is paying the penalty for that crime has surely a right to expect that that woman will care enough for him to remember and visit him while he is the servant of the state.

Then there is mother’s love, never failing, never even wavering in its unassailable constancy, and that accounts for one-half the visitors to the Sing Sing convicts. Thirteen hundred men are confined at Sing Sing, and the army of women—sad women who are sad because of the thirteen hundred—must easily equal the convicts in number.

Many a romance brought to a tragic climax by the merciless hand of the law is suggested by these untiring visitors. Even the ubiquitous hackmen who infest the Sing Sing railway station seem to appreciate this, for when these unhappy ones alight from the trains and look uneasily and self-consciously about, the drivers realize intuitively the nature of their errand and treat them with a deference rarely met within their class. They approach respectfully, and in subdued tones say kindly, “To the prison, madam?” or, “Right this way to the prison.”

About one visitor only is there any mystery. Others give their names and go to see some convict who is known to the keepers. This one goes veiled, and no one knows who it is she goes to see.

A tall, lithe, graceful woman, attired all in black and wearing a heavy black veil, occupied a seat in a car directly in front of and opposite that of the writer recently.

She was uneasy and restless, though not obtrusively so; she carried herself with the fine reserve of a woman of breeding accustomed to do just such things. Sometimes she would look anxiously about the car, as if in fear of being recognized, though with her veil recognition, even by an intimate friend, would have been clearly impossible.

An old-time hackman at the Sing Sing station approached her as she alighted. She got into his ramshackle conveyance as if she had been in it before, and it rattled up the hill and over the stony road along the bluff to the prison a few hundred yards in advance of the equally noisy conveyance of the writer.

It was the hour at which the convicts, having finished their evening meal in the great feeding hall—it would raise the ghost of Brillat Savarin to call it a dining-room—march in lock-step to their cells, in long, single files. They come through the stone-flagged prison-yard with a steady, machine-like shuffle of their heavy prison shoes. Keepers stand about with heavy sticks in their hands.

By the entrance to the long granite building containing the tiers of cells are two great open boxes of bread. Each striped miserable reach out and takes a piece with his left hand as he passes. Slung on the right arm of each is an iron solp pail on which is painted the prisoner’s number. The shuffle of the slowly-moving line continues for perhaps twenty minutes, at the end of which time each of the 1,300 has, with his supper in one hand and his slop-pail in the other, been locked in his cell.

The woman had been shown to the yard, and stood, a keeper by her side, under the portico of the inhospitable-looking hospital building. The long lines of convicts marched toward her and turned not ten feet from where she stood, and marched past the bread-box into the building. She supported herself with one daintily gloved hand against the stone wall, and, leaning forward in an attitude of eager interest, faced down the approaching line.

She tapped the pavement impatiently from time to time with the tow of her neat boot.

Some one in that long line riveted her attention; but there were hundreds there, and the veil prevented any one from seeing which striped one it was.

The prisoners all turned away their heads as they passed the woman. Was it a prison rule that prompted this, or a sense of shame that has survived hardening crime? Not one did otherwise. Many faces flushed, and if any one in that line recognized the trim figure and graceful pose of the strange woman he could never be detected by the flush, for flushed faces were too numerous.

When the last man on the last line a Negro on crutches, who killed a policeman on Wall Street, had disappeared in the door, the woman was escorted out by the keeper. She thanked Principal Keeper Connaughton for his courtesy, which to all visitors, men and women, is always the same. Her voice was pleasant, and there were no tears in it. Her manner indicated nothing in particular, and certainly not grief. She was driven away to the station and returned to New York.

This woman’s visits occur once every two months. Sometimes the interval between them is longer, and sometimes, but seldom, she misses one.

She has been coming for nearly three years, and her visits are always at the same hour. She sees all the prisoners in their lockstep march, and no one connected with the prison knows her name. No one in the prison has ever seen her face.

There are two ways of accounting for the periodical visits of this mysterious unknown. She either loves or hates, with a greater love or a greater hate than ordinarily, someone of the Sing Sing convicts. Perhaps it is love that impels her to remain veiled, and thus to spare the object of her affections humiliation and shame. Unrequited love, perhaps, leads her to conceal her face. Possibly her hate of some one in that long line of erring men derives a certain pleasure from the sight of him in the moment of his disgrace.

Who can tell why she hides her face? Is it because of love or hate?

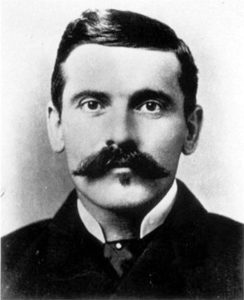

Doc Holliday Obituary, originally published in the November 12, 1887 edition of the Ute Chief, Glenwood Springs, Colorado – J. A. Holliday died, in Glenwood Springs, Colorado Tuesday, November 8, 1887, about 10 o’clock a.m., of consumption.

Doc Holliday Obituary, originally published in the November 12, 1887 edition of the Ute Chief, Glenwood Springs, Colorado – J. A. Holliday died, in Glenwood Springs, Colorado Tuesday, November 8, 1887, about 10 o’clock a.m., of consumption.

Below is an Old West candy recipe from the October 23, 1893

Below is an Old West candy recipe from the October 23, 1893