Born in Maine, Orlando Robbins left home at the age of seventeen and headed out

west. Eventually ending up in the gold fields of Idaho, in 1864 he became the deputy sheriff of Idaho City.

With the Civil War taking place in the east, the miners were polarized into Union and Confederate camps. Robbins’ major job was separating and arresting drunken miners supporting their individual cause.

As Independence Day approached, the Confederate supporters said they were not going to allow any Yankee sing the “Star Spangled Banner.” Now, Robbins, a Union supporter, was determined that no one was going to tell him what to do. So, on July 4, 1864 Orlando Robbins walked into a tavern crowded with southern sympathizers, climbed on a pool table, pulled his two pistols, and with the tavern in complete silence started singing, “Oh, say can you see by the dawn’s early light.” After finishing, he walked out, and the crowd parted like the Red Sea for Moses.

From deputy sheriff of Idaho City, Robbins went on to be deputy sheriff of Boise, and then United States marshal. In 1868 a gun battle had been going on for

weeks between two mining operations in Silver City. Sent by the governor to settle things, Robbins did it in one day. In 1876 six bandits held up the Silver City stage. Robbins had them all in jail within two days. At the age of 46, Robbins covered 1,280 miles in just 13 days to catch outlaw Charley Chambers. When he was in his 60’s he was still a lawman dealing with

outlaws one third his age.

November 6, 2017 | Categories: Old West History | Leave A Comment »

It seems that everyone in the

Old West had nicknames… And some of them were strange. But, none was as strange as Charles Bryant’s. He was called “Black Faced Charlie.” It seems that when he was a young man he was shot point-blank in the face. The bullet just creased his cheek. But, the burnt powder coming out of the pistol imbedded in his face, giving him his nickname.

Bryant joined the Dalton gang. And during the gang’s shootout with a posse was heard to say something like, “Me, I want to get killed in one heck of a minute of action.” Well, Bryant put it out there, and on August 23, 1891, he got his wish.

Being arrested, Bryant had to be transported to jail by Deputy U.S. Marshal Ed Short. Marshal Short was transporting the handcuffed Bryant in a train baggage car when he had to visit the john. Marshal Short gave his pistol to the railroad messenger and left. The messenger put the pistol in a desk drawer and went about his chores.

Unnoticed, Bryant moved around to the desk and got the pistol, just as Marshal Short entered the baggage car. Bryant placed one shot into Marshal Short’s chest. Short, carrying a rifle, shot Bryant… severing his spine. Bryant continued firing his pistol until it was empty. The rest of his shots went wild.

Bryant was killed in one heck of a minute of action as he wished. Marshal Short helped the messenger pick up Bryant’s body. Marshal Short then laid down on the cot and died. He was also the victim of heck of a minute of action.

Both bodies were left on the train platform at the next stop.

September 18, 2017 | Categories: Old West History | Leave A Comment »

Born in Austin, Texas in 1856, Frank Jones joined the Texas Rangers at the age of 17. He saw his first action when he and two other Rangers were sent after some Mexican horse thieves. The horse thieves ambushed the Rangers. Frank’s two companions were immediately taken out, but Frank was able to kill two of the bandits and capture a third.

Frank was promoted to corporal and later to sergeant. Once again while chasing a large gang of cattle rustlers, Frank and his six Ranger companions were ambushed. Three of the Rangers were killed, and Frank and the other two Rangers were captured.

Now, it would have been much better for the rustlers if they had also killed Frank, for while the rustlers were congratulating themselves on their victory, Frank grabbed one of their rifles, and proceeded to kill all of them.

A few years later, now a captain, while traveling alone, Frank was again ambushed. This time by three desperadoes who shot him, and left him for dead. With a bad chest wound, Frank tracked the three men down on foot until he found their camp. He waited until dark; took one of their rifles; shot one and brought the other two back to stand trial.

Over the next few years Frank continued his confrontations and victories over outlaws. But on June 29, 1893 Frank went on his last mission. He and four other Rangers went after some cattle thieves on the Mexico border. This time they did the ambushing. But it didn’t turn out well for Frank. In the ensuing gunfight this man of many lives was finally killed.

September 4, 2017 | Categories: Old West History | Leave A Comment »

For development to take place there has to be men of vision. Men of vision developed the pony express to deliver mail to the western frontier faster than stagecoach. Unfortunately for the pony express, at the same time other men of vision were developing a faster way to connect the east with the west.

One such man was Fred A. Bee. Fred lived in Virginia City, Nevada. On July 4, 1858 he and four partners started the Placerville, Humboldt and Salt Lake Telegraph Company. Carson Valley residents had passed a bond referendum for $1,200 toward the project, and so they started immediately. By fall of that year the telegraph had connected Placerville, California with Nevada. Six months later it arrived in Carson City, and finally it stretched all the way across Nevada.

In the process of doing this, they had to cross over the rugged Sierra Mountains. Less than ten years later the Central Pacific Railroad would spend about 20 million dollars crossing those same mountains. The ground was granite. The winds were strong, and the snow deep.

With limited funds and manpower Fred Bee decided that rather than blast holes in the granite for telegraph poles, they would string the wire on the pine trees that had been able attach themselves to the granite and withstand the winds and snow. So, the telegraph wire was strung from treetop to treetop with some spans of wire being quite long. This led people to nickname the Placerville, Humboldt and Salt Lake Telegraph Company, “Bee’s Grapevine Line.” But when it was completed, even the skeptics used it with pride.

Two years later Congress authorized constructing the Overland Telegraph Company, and Fred A. Bee’s Grapevine Line became a major link in the completion of the transcontinental telegraph.

August 19, 2017 | Categories: Old West History, Uncategorized | Leave A Comment »

Henry Newton Brown was born in Missouri in 1857. Migrating west, he did some buffalo hunting. At the age of nineteen he ended up in Lincoln County, New Mexico during the time of the Lincoln County War. Brown became a member of the Regulators, the quasi-legal group led by Billy the Kid. After being involved in a couple of the shootouts, he was indicted for murder. Before warrants could be served, Brown took off to Texas.

Henry Newton Brown was born in Missouri in 1857. Migrating west, he did some buffalo hunting. At the age of nineteen he ended up in Lincoln County, New Mexico during the time of the Lincoln County War. Brown became a member of the Regulators, the quasi-legal group led by Billy the Kid. After being involved in a couple of the shootouts, he was indicted for murder. Before warrants could be served, Brown took off to Texas.

Henry Brown didn’t smoke, drink or gamble. He frequently dressed in a suit, and he could handle a gun…the perfect candidate for a lawman. So, he was appointed deputy sheriff of Oldham County. Shortly afterward he went up to Caldwell, Kansas where he became deputy marshal. And when the city marshal resigned, Brown stepped into that position. Brown did so well that the citizens of Caldwell gave him a handsomely engraved Winchester rifle.

On April 30, 1884, after his third appointment as marshal, Henry Brown and his assistant, Ben Wheeler took a few days off to go up to Medicine Lodge, Kansas. The purpose of their trip wasn’t to get in a few days of rest, but to rob the Medicine Lodge bank. In the process Brown killed the bank president and Wheeler killed the cashier.

The men were captured and locked away in jail. However, that night a mob stormed the jail with ropes in hand. Henry Brown tried to escape. But before he could get far, a shotgun blast ended the whole affair. The people of the Old West could accept their lawmen having a criminal background, but not committing crimes while wearing a badge.

July 12, 2017 | Categories: Old West History | Leave A Comment »

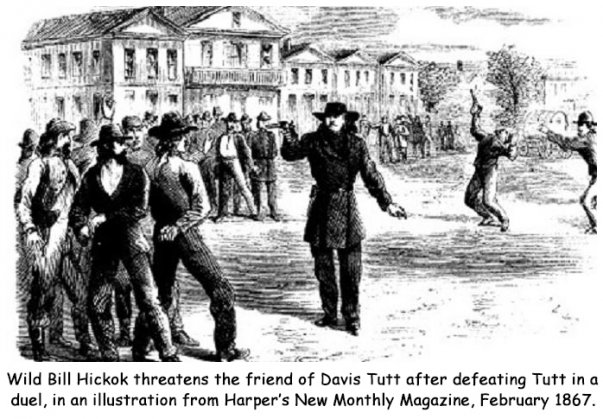

In the early 1860’s two men of strong will, Dave Tutt and Wild Bill Hickok had a couple of meetings which ended in fist fights.

In 1865, working on the principal of “the third time’s a charm,” they met again. This time William Hickok, or Wild Bill Hickok, as he was now known, seemed to get along with Dave Tutt. Part of the reason could have been that Dave had his comely sister with him, and Wild Bill took a likin’ to her. Dave Tutt was doing much better financially than Wild Bill, and Dave loaned Bill money from time to time.

Now enters the wild card. A Susanna Moore came to town. Wild Bill had supposedly known her during before this. So Wild Bill started sparking her along with Dave Tutt’s sister. Susanna was not a woman to share her man, so she started flirting with Dave Tutt.

The whole affair came to a climax on July 20, 1865. Wild Bill Hickok was playing poker when Dave Tutt came up to him and grabbed his pocket watch that was lying on the table. Dave said it was payment for what Wild Bill owed him. Wild Bill allowed Dave to take the watch, but let it be known not to wear the watch in public.

The next morning Wild Bill saw Dave on the street wearing the pocket watch. With his pistol held at his side, Dave started walking toward Wild Bill. In response to a warning from Wild Bill, Dave shot off a round. Making sure he didn’t hit the pocket watch, Wild Bill shot Tutt through his heart.

Wild Bill learned that a person can’t play two fiddles at one time and make pretty music.

July 5, 2017 | Categories: Old West History | Leave A Comment »

Although it wasn’t a relationship most people would expect, King Fisher and Ben Thompson were friends. The reason their friendship was unusual was that both men were hard cases.

King Fisher dressed in a flamboyant style. He wore a gold braided sombrero, silk shirts and gold-embroidered vests. His chaps were made of Bengal tiger skin. He didn’t get the tiger skin from a safari, but a raid on a circus.

Fisher traded in cattle. He took cattle that he had stolen in the United States to Mexico, and traded them for cattle that had been stolen in Mexico… And buyers didn’t care as long as the cattle didn’t have a brand from the country in which it was sold.

Ben Thompson’s reputation wasn’t much better. Ben didn’t care on which side of the law he walked, as long as he could use his pistol and intimidate people. Sensing the opportunity for a good fight, he even went to Mexico and joined Maximilian as a mercenary, rising to the rank of Colonel. Ben Thompson had also spent time as the city marshal of Austin, Texas.

These two hot heads met up in San Antonio on March 10, 1884, and decided to have an evening out. Celebrating, as friends do, they ended up going to the Vaudeville Variety Theater. Maybe because of too many drinks, or advancing age, Ben Thompson evidently didn’t remember that a couple of years earlier he had killed the proprietor of that establishment. Within minutes of their arrival four of the dead man’s friends, including the bartender and one of the actors, opened fire. Ben Thompson ended up with 9 slugs in him, and his friend King Fisher had 13. It was a tough night out for the boys.

June 18, 2017 | Categories: Old West History | Leave A Comment »

When Mexico gained their independence from Spain, Mexico gave the Anglo-Texans considerable autonomy. But in 1835, Santa Anna proclaimed himself dictator of Mexico; he imposed martial law, which fed the flames of the Texan’s resistance. So, Santa Anna decided to personally lead his army to wipe out these Anglo-rebels.

Early in March of 1836, while Santa Anna was attacking and defeating a small force of Texans at an abandoned mission called the Alamo, Santa Anna’s chief lieutenant, General Urrea was heading toward another group of 400 Texans defending a town called Goliad.

As General Urrea’s 1400 man army approached, James Fannin, the leader of the Texans, was indecisive as to whether he should defend Goliad or rush to the aid of the Alamo. At the last minute, Fannin decided to retreat. By then General Urrea’s men had surrounded the Texan force. Trapped on an open prairie Fannin realized there was no escape, so he surrendered.

Fannin and his men felt they were soldiers surrendering as prisoners of war. Unfortunately, Santa Ana had stated before that he considered the rebels to be “perfidious foreigners” or in a more common term “traitors,” and they would be treated as such.

On March 27, 1836, General Urrea took the over 340 prisoners and shot them at point blank. Those who didn’t die during the first volley were hunted down and killed by bayonet or lance. Then General Urrea and his men moved on, leaving the dead Texans unburied.

When news got out about the Goliad massacre, the battle cry became “Remember Goliad and the Alamo!”

May 28, 2017 | Categories: Old West History | Leave A Comment »

It was early 1877. The Civil War had been over for more than ten years. But blacks still didn’t have the freedom they had hoped for. Tenant farming had replaced the plantation system. Because of the price of rented land, and supplies, the black farmer seldom broke even at the end of the year. So, they started looking for somewhere else that would give them true opportunity.

Prior to the Civil War, by the vote of the residents, Kansas had changed from a slave to a free state. Although blacks had moved to Kansas on an individual basis, the first serious attempt to establish a black colony was on March 5, 1877 when Benjamin Singleton led a group from Tennessee to Baxter Springs located in the southeast corner of the state. Cherokee County Colony, Singleton Colony, Hill City, and Nicodemus Town followed. Most failed because of poor leadership, the transient nature of the emigrants, and having only marginal land available for settling.

It’s estimated that between fifteen and twenty thousand blacks migrated to Kansas in just a two-month period. Realizing the loss of cheap labor, southern landowners tried to stop the migration with intimidation and attacks against those involved in the “Colored Exodus.”

The biggest obstacle for blacks was that they had little or no money when they started their trek to Kansas. Many had only the possessions they could carry on their backs. However, they were assisted with relief efforts along the route from churches and private citizens.

By 1879 word got back to the south that the Kansas immigrants were facing tremendous problems in establishing a new life, and almost as fast as it started, the Kansas immigration dropped off to a trickle, and stopped.

May 22, 2017 | Categories: Old West History | Leave A Comment »

William Averill Comstock was a military scout who could, “easily read all the signs Indians left for the information of other Indians, could interpret their smoke columns used in telegraphing, and after a party had passed, could tell with remarkable accuracy from its trail how many were in the party.”

William Averill Comstock was a military scout who could, “easily read all the signs Indians left for the information of other Indians, could interpret their smoke columns used in telegraphing, and after a party had passed, could tell with remarkable accuracy from its trail how many were in the party.”

Comstock was the prototypical military scout. He earned the name “Medicine Bill,” because he bit off the finger of a young Sioux woman who had received a rattlesnake bite.

But William Comstock had a secret past. Not that he was some bad criminal on the run, but the opposite. He was the grandnephew of James Fenimore Cooper. You see, Cooper wrote about the “noble savage”, and the whites on the western frontier hated Cooper’s romantic tales about the savage Indian.

In August of 1868 a band of Indians attacked a village near Hays, Kansas.

Comstock and another scout named Abner Grover were sent to the camp of Cheyenne chief Turkey Leg to see if the rampaging braves could be brought under control. While in negotiations, Turkey Leg received word that the military had killed several Indians in retaliation. The negotiations were over, and on August 16, 1868, while traveling home Comstock was killed.

Now, the interesting thing is that William Comstock was George Armstrong Custer’s favorite scout. One of the few people Custer would listen to. The question is, would the Little Big Horn have taken place if Comstock had been riding alongside of Custer instead of dying eight years earlier?

April 15, 2017 | Categories: Old West History | Leave A Comment »

In 1837 Mexico didn’t like Texas being an independent nation. And then, when Texas became our 28th state, it was just too much. With diplomacy breaking down, in 1846 President Polk declared war on Mexico.

In battles it wasn’t unusual for the Mexican forces to outnumber the U. S. forces as much as four to one. But superior weapons and battle tactics gave the American forces victory. And in less than a year and a half, American soldiers occupied Mexico City.

Envisioning the possibility of additional slave states, southern politicians started calling for the conquest of all of Mexico. The northern states, not wanting additional slave states, not only opposed the conquest of Mexico; they introduced bills that said “neither slavery nor involuntary servitude” would exist in any territories acquired by the Mexican War.

Finally, on February 2, 1848, after three months of negotiations, a treaty was signed in the Mexican city of Guadalupe Hidalgo.

The treaty said the United States would pay Mexico 15 million dollars. The U. S. would take care of any claims American individuals had against Mexico, by paying these Americans 3.25 million dollars. In turn the United States got over one million square miles of territory. It included all or part of what is now California, New Mexico, Utah, Nevada, Arizona and Colorado.

Counting the money given to Mexico and the Americans, it cost the United States about $15 a square mile. Not a bad deal.

March 4, 2017 | Categories: Old West History | Leave A Comment »

George Armstrong Custer seemed to always live on the edge. Even while at West Point, where, incidentally, he graduated at the bottom of his class, Custer was almost expelled because of demerits for actions like food fights in the cafeteria.

George Armstrong Custer seemed to always live on the edge. Even while at West Point, where, incidentally, he graduated at the bottom of his class, Custer was almost expelled because of demerits for actions like food fights in the cafeteria.

However, one of the low points in his career took place on November 25, 1867 when he was court-martialed. Supposedly, Custer’s officers fell into two categories…those who were related to him, and those who hated him. As for the enlisted men, they fell into one category…those who feared him.

Custer was found guilty on eight counts. They included being absent without leave from his command. He had left his post to visit his wife, Libby. He had also taken along troopers as escort during this trip. Another count was shooting deserters without trial. Incidentally, when Custer left to visit his wife, he was considered a deserter himself.

Libby Custer

The testimony of Captain Frederick Benteen, an officer with Custer at Little Big Horn, was particularly damning. Other charges included abandoning two men, failing to recover two bodies, and cruelty to three wounded troopers. The average officer being found guilty on any of these counts would have meant the end of his career. But George Custer wasn’t average. His sentence was, “to be suspended from rank and command for one year, and to forfeit his pay proper for the same time.”

At the end of the year Custer’s friend and advocate, General Phil Sheridan, called him back to active duty. Custer felt he had to do something spectacular to redeem himself. And he did on November 27, 1868, when Custer and 800 men attacked the peaceful camp of Black Kettle that was flying the American Flag and a white truce flag.

February 27, 2017 | Categories: Old West History | Leave A Comment »

Granville Stuart was born with his brothers in West Virginia, and at a young age, he started migrating west. After reaching Montana, Granville and his brother, James discovered gold there, and they spread the news, the result of their writing their brother back east. Unfortunately, the Stuarts didn’t get rich from their discovery. Granville Stuart was born with his brothers in West Virginia, and at a young age, he started migrating west. After reaching Montana, Granville and his brother, James discovered gold there, and they spread the news, the result of their writing their brother back east. Unfortunately, the Stuarts didn’t get rich from their discovery.

In 1863, Granville rode with the vigilantes that wiped out the “The Innocents”, a gang led by Henry Plummer, who also happened to be the town marshal.

Being interested in cattle, and seeing the lush grasslands in Montana, Granville helped start the cattle industry there. By 1883, things were not going well for the cattlemen. Because of rustling, cattle attrition was considerable. So Granville, using his earlier experience, help organize the Montana Vigilantes, who were known as “The Stranglers”, the result of their frequent use of the rope… And supposedly as many as 70 men ended up with hemp around their necks.

The harsh winter of 1886 all but wiped out Montana’s cattle, and Granville left the cattle industry behind for…an appointment as Minster to Uruguay and Paraguay. For five years, he lived in South America, only to return to Montana to become the Butte, Montana… librarian.

Granville Stuart has been described as an intellectual, a fine writer and a wise man with an engaging sense of humor. Although he had no formal training, Granville was an excellent artist. He wrote and illustrated three books. One was a geographical description of Montana. Another was a narration of the discovery and early settlement of Montana.

Granville was commissioned by the state of Montana to write a history of the state. But unfortunately, he died on October 2, 1918 before he could finish it.

I think you can agree that Granville Stuart was truly a renaissance man.

|

January 16, 2017 | Categories: Old West History | Leave A Comment »

President James Monroe

Two speeches, each delivered on December 2, that happened to be 22 years apart, resulted in affecting the development of the west more than any other single action during the 1800’s.

On December 2, 1823, during his seventh speech before Congress, President James Monroe introduced the concept that, for reasons of national security, all European influence should be removed from the areas immediately surrounding the United States. So, the United States started peacefully acquiring territories owned by European countries. This policy came to be known as the Monroe Doctrine.

On December 2, 1845, 22 years later, President James Polk made his first address to Congress. During that speech he reasserted the Monroe Doctrine. But President Polk went one step beyond, by stating his willingness to use force, if necessary, in removing European influence from areas determined for the expansion of the United States. President Polk felt that the expansion of the United States was its “manifest destiny.”

President James Polk

President Polk wanted the United States to annex Texas, acquire California and gain total control of the Oregon territory. Standing in the way of our doing this were just the countries of Mexico, Great Britain and France.

Fortunately, Great Britain peacefully surrendered its claim on the Oregon territory south of the 49th parallel. With the annexation of the Republic of Texas into the United States, Mexico declared war. As the United States entered into the war, President Polk was afraid that Great Britain and France would come in on the side of Mexico. But that never happened.

In 1846, with the defeat of Mexico and the Treaty of Guadalupe Hadalgo, the vision of President Polk’s speech of December 2, 1845 was realized. The final pieces of the puzzle had fallen into place. The United States now controlled the areas that one day would become the Pacific Northwest, Texas, California, Arizona, New Mexico, Nevada and Utah.

January 8, 2017 | Categories: Old West History | Leave A Comment »

December 24, 1884 began like any other day in the small town of Helena, Texas. Helena was known as the toughest town on earth… and the town was filled with cowboys waiting for the spring cattle drives going north, Civil War veterans, highwaymen and gunmen.

December 24, 1884 began like any other day in the small town of Helena, Texas. Helena was known as the toughest town on earth… and the town was filled with cowboys waiting for the spring cattle drives going north, Civil War veterans, highwaymen and gunmen.

Meanwhile, at one of the bars, a drunken cowboy shot off his pistol, a normal occurrence at the bars in Helena… But this bullet accidentally killed a 23-year-old Emmett Butler. Now, typically an accidental killing was given little notice. But Emmett Butler was the son of William G. Butler, the wealthiest rancher in the area.

Upon hearing of his son’s death, William Butler came to town demanding his son’s killer be turned over to him…And when the town refused, he left vowing to, “Kill the town that killed my son.”

Around Helena, little was thought of his remarks. No one, no matter how wealthy, could kill a town as prosperous as Helena, Texas. Besides, it was the county seat.

A year after Emmett Butler’s death, the San Antonio Railroad was laying track through the area. William Butler offered the railroad free right of way and $35,000 on one condition… And that was that the railroad would build its tracks seven miles southwest of Helena, Texas.

The railroad agreed, and after the track was laid, the new town of Karnes City, Texas sprang up next to the railroad tracks… and Helena businesses started moving to Karnes City.

The final blow came nine years later, almost to the day, after the death of Emmett Butler… when on December 21, 1893, the citizens of the county voted to move the county seat to Karnes City.

And Helena, Texas, true to the promise of William Butler… died.

December 19, 2016 | Categories: Old West History | Leave A Comment »

In the early 1800’s the Southwest was part of Mexico, and Mexico was under the domination of Spain. Because the Spanish were afraid of the expansion of the Anglos, they closed the area to anyone from the states. Any American trader they found in the area ended up in jail.

In the early 1800’s the Southwest was part of Mexico, and Mexico was under the domination of Spain. Because the Spanish were afraid of the expansion of the Anglos, they closed the area to anyone from the states. Any American trader they found in the area ended up in jail.

In 1821 William Becknell and four other men were doing some trading with the Comanche Indians on the American controlled side of the Rockies when they encountered some Mexican troops. The troopers told Becknell that Mexico had won their independence, and the area was once again open to Americans. Immediately Becknell headed for Santa Fe, where he was able to sell everything he had at an enormous profit.

Five months later he was back in Missouri looking for men “to go westward for the purpose of trading for horses and mules and catching wild animals of every description.” With less than half the volunteers he was looking for, on November 16, 1821 Becknell and three wagonloads of merchandise arrived in Santa Fe.

Becknell’s delivery of goods to Santa Fe was a feat to be admired, but the delivery was not what made him famous. It was the route he took to get there.

For decades Mexican traders had used a route that went over a dangerous high mountain pass. What Becknell did was to create a shortcut that led across the Cimarron Desert. The route created by Becknell became known as the “Santa Fe Trail”. It became one of the most important Old West trading routes used by merchants and travelers until the 1870’s with the arrival of the train.

November 15, 2016 | Categories: Old West History | Leave A Comment »

Coal was very important for the operation of the railroad. And because of that, many railroads controlled their supply of coal by owning the coal-mining operations. One such mining operation owned by the Union Pacific Railroad was located in Rock Springs, Wyoming.

Coal was very important for the operation of the railroad. And because of that, many railroads controlled their supply of coal by owning the coal-mining operations. One such mining operation owned by the Union Pacific Railroad was located in Rock Springs, Wyoming.

In 1885, the miners were trying to unionize. In order to break their efforts, the Union Pacific brought in Chinese laborers to work the mines. The Chinese were hard workers, but they neither understood the concept of unionizing, nor were they interested.

Frustrated, on September 2, the striking miners decided to strike out at the easiest and most visual target they could find. About 150 miners descended upon the Chinatown area of Rock Springs, with the objective of chasing the Chinese out of the area. When the miners started approaching, most of the Chinese abandoned their businesses and homes, and hid in the hills. Unfortunately, not everyone made it. Without weapons to defend themselves, 28 Chinese were killed, and 15 others wounded.

A week later, the U. S. Military arrived and escorted the remaining Chinese back from the hills. Many of them returned to the mines. Even though the identity of the participating miners was known, the local authorities took no legal action against them. However, the Union Pacific did fire 45 miners for their part in the massacre.

This was but one of a number of violent events that took place throughout the West. It was symptomatic of the hatred of the Chinese that three years earlier had resulted in the passing of the Chinese Exclusion Act that prohibited further Chinese immigration into the United States. Incidentally, the Chinese Exclusion Act remained the law until World War II when China joined on the side of the Allies.

November 1, 2016 | Categories: Old West History | Leave A Comment »

Johnnie Brughuier was born the son of a white father and Sioux mother near present day Sioux City, Iowa. His father sent him to St. Louis for an education. When he returned home, on December 14, 1875, in the process of breaking up a fight between his brother and another man, Johnnie killed the other man. Afraid that he would be arrested for murder, Johnnie fled to the camp of Sitting Bull.

Johnnie, now called “Big Leggins”, became Sitting Bull’s personal secretary and interpreter. His first opportunity as interpreter was between Sitting Bull and General Nelson Miles. The meeting didn’t go well and five days later 2,000 of Sitting Bull’s Sioux were forced to surrender. However, Sitting Bull and Johnnie escaped.

Johnnie yearned to return to white civilization. So he met with General Miles and explained that he had joined Sitting Bull because of his fear of being arrested for murder. Convinced of his sincerity General Miles said he would do what he could about the murder, and gave Johnnie a job… It was to meet with Sitting Bull, the man he had just betrayed, and convince him to surrender. On several occasions Johnnie was sent on missions that seemed to be certain suicide. But each time he returned, either successful in his mission, or bringing back vital information.

In 1879 his past finally caught up with him, and he was arrested for killing the man back in 1875. At the trial General Miles testified on his behalf. It took the jury just one half hour to bring back a verdict of not guilty.

The work of Johnnie Brughuier saved the lives of hundreds of whites and Indians. We’ll never know if he would have taken the same path had the tragedy of December 14, 1875 not happened.

October 9, 2016 | Categories: Old West History | Leave A Comment »

On September 14, 1901 with the death of President William McKinley, his Vice President, Theodore Roosevelt was sworn in as the 26th President of the United States. Roosevelt was a very unlikely man to become the leader of our country.

It was just 17 years earlier that a double tragedy struck… Within a 12 hour period both his wife and his mother died. Trying to get as far away from Washington as possible, and abandoning his political career, Roosevelt went to the Badlands of the Dakota Territory to become a rancher. Although he never made money as a rancher, the experience did change his life.

He never looked like a cowboy. But he had the soul of a cowboy, and gained the respect of his fellow-ranchers. When a gang stole his riverboat, he went after them, and weeks later brought them to justice. A bully tried to make Roosevelt buy him a drink by calling him “four eyes,” Roosevelt proceeded to punch out the bully.

After three years as a rancher, Roosevelt returned to Washington with a new zeal for life. He later said that were it not for his experience in the West he would not have had the drive to become the President of the United States.

Roosevelt’s experience out west also instilled in him an appreciation of the natural beauty of the West and the need to preserve it for future generations. During his time as President, Roosevelt gave the public 230 million acres of national forest land. And he doubled the number of national parks, including Yosemite.

Although Theodore Roosevelt spent the vast majority of his life back east, he always considered himself a westerner at heart.

September 30, 2016 | Categories: Old West History | Leave A Comment »

For people of the Old West gambling was a way of life. They risked their life by going into Indian Territory for furs, precious metal or land. They staked everything they owned on a herd of cattle being driven north. And for sure they enjoyed a game of chance.

There was faro, euchre, monte, casino, and, of course, poker… which, incidentally, was always dealt to the left of the player to make it easier to pull a gun with the right hand in case of irregularities. The origin of most games of chance came from Europe, with the exception of the old three walnuts and a pea, which started in America, probably on the streets of New York, where it still prospers.

Not only did cowboys lose their wages, but whole herds of cattle, and a cattleman’s entire wealth would change hands over night. A few wives were even offered to “match the pot.”

On June 15, 1853, in Austin, Texas Major Danelson and Mr. Morgan sat down to play poker, and evidentially with little to go home to, forgot to quit. The game went on for a week… then a month… a year became years. The Civil War broke out, was fought and lost, but these two Texas gentlemen still dealt the cards. Finally in 1872, 19 years after it started, both men died on the same day… but the game continued. Their two sons took over, and played for 5 more years.

Finally the game ended in 1877 when a railroad train killed one of the sons, and the other went crazy. Not that all of them weren’t crazy in the first place.

September 25, 2016 | Categories: Old West History | Leave A Comment »

The year was 1867. The Red Cloud War had been going on along the Bozeman Trail for almost two years. On August 1 some 500 Sioux, Cheyenne and Arapaho led by Dull Knife and Two Moon, attacked a small detachment of eight troopers and nine civilians that were led by Lieutenant Sternberg. At the time of the attack, Lieutenant Sternberg’s group was in the open crossing a hayfield. Fortunately, they were able to make it to the shelter of a nearby corral. Even more fortunately, the troopers and civilians had repeating rifles.

The Indian’s traditional plan of attack against single shot, breech-loading rifles, would be to draw fire, and while the rifles were being reloaded, attack in force. But, with repeating rifles, the fire was constant. Stymied, the Indians decided to set fire to the hay field and burn out the whites. But it wasn’t to be. As the fire got close to the corral, a strong wind came up, and put it out.

By late afternoon, the Indians decided to take their fight elsewhere. During the Hayfield Fight, as it was called, 20 warriors were killed and more than 30 seriously wounded. For the other side, only Lieutenant Sternberg, two soldiers and one civilian were killed.

The interesting thing about the conflict was that it took place near Fort C. F. Smith, where it could be seen and heard. Although Fort Smith contained a garrison of troops, none was ever sent. About seven months earlier at Fort Phil Kearny, Captain Fetterman and a command of eighty men were wiped out when they left their fort to help some woodcutters. It’s speculated that the commander was in fear of a repeat of the Fetterman Massacre.

September 11, 2016 | Categories: Old West History | Leave A Comment »

John Colter was a member of the Lewis and Clark Expedition during their trailblazing trip through the west. This was his first venture into the new frontier, and he liked what he saw. So, on June 15, 1806 John ventured out on his own.

He ended up near present day Custer, Wyoming where he made friends with some Crow Indians. John accompanied them on a raid against the Blackfoot, during which John killed a Blackfoot. This was unfortunate because now the Blackfoot Indians wanted John’s hair.

About a year later the Blackfoot captured John and a fellow trapper. In the process John’s friend was killed. They had something special for John. He was stripped of his clothing, and told to run. With a 500-yard head start, the braves started after him.

Even with bare feet and body being cut by the rocks and brush, John managed to outdistance all but one brave. Just as the brave caught up with him, John turned and faced the Indian. Startled at the bloody sight, the Indian stumbled, and John killed him. Even with the remaining Blackfoot Indians still in pursuit, John was able to travel the 250 miles to safety.

If, at this point, you’d say, “I’d never return to Blackfoot country,” you wouldn’t have the pluck of John Colter. Because John went back, but after 5 of his companions were killed; he finally decided to leave.

John got married and became a farmer. When he died, his wife abandoned the cabin and left John on his deathbed. In 1926, the remains of John Colter and his cabin were found, and he was finally given a formal burial.

August 28, 2016 | Categories: Old West History | Leave A Comment »

In 1843 a trading post was built in what is now Hutchinson County, Texas. Over the years the trading post was abandoned, and it fell into disrepair. Thirty years later, about a mile away from the original post, another trading post was established. It comprised of a store, saloon, blacksmith shop and another building. Whites called it Adobe Walls.

Chief Quanah Parker considered its existence an act of war. His medicine man, Isatai, also known as “Little Wolf”, convinced Parker that the Great Spirit had told him any Indian who attacked Adobe Walls painted with a special yellow paint would be invincible to bullets.

Because of their log construction and sod roofs, the buildings were virtually impregnable. In addition, the buildings contained 29 buffalo hunters, including Bat Masterson, all with 50 caliber “buffalo guns.”

On June 27, 1874, 700 Comanche, Cheyenne, Kiowa and Arapaho warriors attacked Adobe Walls head on. With the buffalo guns taking their toll, and his horse shot from beneath him, Quanah Parker realized the yellow paint wasn’t working.

Four buffalo hunters were killed. Three were caught outside the buildings, and the fourth died of an accidental self-inflicted wound. It’s not known exactly how many Indians were killed, because most of the dead and wounded were carried away.

Medicine man, Isatai, tried his best to come up with excuses for the failure. He discovered a brave had killed a skunk prior to the battle, and said that the skunk’s killing had caused the Great Spirit’s spell to be broken. But the braves would have none of it. Later, when asked what Isatai meant in English, the Indians said it was “Coyote Droppings.”

August 23, 2016 | Categories: Old West History | Leave A Comment »

Deacon Miller was a little man who was quiet, and never cussed. He dressed like a traveling minister, and was an avid churchgoer. At the same time, this Jekyll-Hyde character was one of the most ruthless assassins of the Old West. It’s estimated that 40 or more people died from lead that came from his guns… Some of them were even his relatives. His contracts were usually carried out on unarmed men from behind a rock or tree, while using a rifle.

Deacon Miller was a little man who was quiet, and never cussed. He dressed like a traveling minister, and was an avid churchgoer. At the same time, this Jekyll-Hyde character was one of the most ruthless assassins of the Old West. It’s estimated that 40 or more people died from lead that came from his guns… Some of them were even his relatives. His contracts were usually carried out on unarmed men from behind a rock or tree, while using a rifle.

There are those who say he was involved with the death of Pat Garrett, the lawman who shot Billy the Kid. A man named Brazel, who was renting Garrett’s ranch confessed to killing Garrett. But at the time, a mysterious man, who fit Deacon Miller’s description, by the name of Adamson, was negotiating the purchase of the ranch. Some feel if he didn’t actually pull the trigger, he paid Brazel to do it. But like many theories about events from the Old West, we’ll probably never know the truth.

Deacon Miller’s last contract kill was on a lawman named Gus Babbitt. As was his style, Miller ambushed Babbitt. Unfortunately, Babbitt lived long enough to describe Miller. Miller and his three helpers were arrested.

Deacon Miller’s last contract kill was on a lawman named Gus Babbitt. As was his style, Miller ambushed Babbitt. Unfortunately, Babbitt lived long enough to describe Miller. Miller and his three helpers were arrested.

Now, Deacon Miller was noted for being a smooth-talker. And he bragged that with his ability to con, and a high priced lawyer, he was going to beat this rap. Some of the Ada, Oklahoma locals believed him. So, on April 19, 1909 they broke Deacon Miller and his three friends out of jail; escorted them to a barn; and hanged them. Deacon Miller went to his reward. And there was little doubt by anyone who knew him, the direction in which that reward was located.

August 4, 2016 | Categories: Old West History | Leave A Comment »

Born in Maine, Orlando Robbins left home at the age of seventeen and headed out west. Eventually ending up in the gold fields of Idaho, in 1864 he became the deputy sheriff of Idaho City.

Born in Maine, Orlando Robbins left home at the age of seventeen and headed out west. Eventually ending up in the gold fields of Idaho, in 1864 he became the deputy sheriff of Idaho City.  It seems that everyone in the Old West had nicknames… And some of them were strange. But, none was as strange as Charles Bryant’s. He was called “Black Faced Charlie.” It seems that when he was a young man he was shot point-blank in the face. The bullet just creased his cheek. But, the burnt powder coming out of the pistol imbedded in his face, giving him his nickname.

It seems that everyone in the Old West had nicknames… And some of them were strange. But, none was as strange as Charles Bryant’s. He was called “Black Faced Charlie.” It seems that when he was a young man he was shot point-blank in the face. The bullet just creased his cheek. But, the burnt powder coming out of the pistol imbedded in his face, giving him his nickname.  Born in Austin, Texas in 1856, Frank Jones joined the Texas Rangers at the age of 17. He saw his first action when he and two other Rangers were sent after some Mexican horse thieves. The horse thieves ambushed the Rangers. Frank’s two companions were immediately taken out, but Frank was able to kill two of the bandits and capture a third.

Born in Austin, Texas in 1856, Frank Jones joined the Texas Rangers at the age of 17. He saw his first action when he and two other Rangers were sent after some Mexican horse thieves. The horse thieves ambushed the Rangers. Frank’s two companions were immediately taken out, but Frank was able to kill two of the bandits and capture a third.

Henry Newton Brown was born in Missouri in 1857. Migrating west, he did some buffalo hunting. At the age of nineteen he ended up in Lincoln County, New Mexico during the time of the Lincoln County War. Brown became a member of the Regulators, the quasi-legal group led by Billy the Kid. After being involved in a couple of the shootouts, he was indicted for murder. Before warrants could be served, Brown took off to Texas.

Henry Newton Brown was born in Missouri in 1857. Migrating west, he did some buffalo hunting. At the age of nineteen he ended up in Lincoln County, New Mexico during the time of the Lincoln County War. Brown became a member of the Regulators, the quasi-legal group led by Billy the Kid. After being involved in a couple of the shootouts, he was indicted for murder. Before warrants could be served, Brown took off to Texas.

William Averill Comstock was a military scout who could, “easily read all the signs Indians left for the information of other Indians, could interpret their smoke columns used in telegraphing, and after a party had passed, could tell with remarkable accuracy from its trail how many were in the party.”

William Averill Comstock was a military scout who could, “easily read all the signs Indians left for the information of other Indians, could interpret their smoke columns used in telegraphing, and after a party had passed, could tell with remarkable accuracy from its trail how many were in the party.”

George Armstrong Custer seemed to always live on the edge. Even while at West Point, where, incidentally, he graduated at the bottom of his class, Custer was almost expelled because of demerits for actions like food fights in the cafeteria.

George Armstrong Custer seemed to always live on the edge. Even while at West Point, where, incidentally, he graduated at the bottom of his class, Custer was almost expelled because of demerits for actions like food fights in the cafeteria.

Granville Stuart was born with his brothers in West Virginia, and at a young age, he started migrating west. After reaching Montana, Granville and his brother, James discovered gold there, and they spread the news, the result of their writing their brother back east. Unfortunately, the Stuarts didn’t get rich from their discovery.

Granville Stuart was born with his brothers in West Virginia, and at a young age, he started migrating west. After reaching Montana, Granville and his brother, James discovered gold there, and they spread the news, the result of their writing their brother back east. Unfortunately, the Stuarts didn’t get rich from their discovery.

December 24, 1884 began like any other day in the small town of Helena, Texas. Helena was known as the toughest town on earth… and the town was filled with cowboys waiting for the spring cattle drives going north, Civil War veterans, highwaymen and gunmen.

December 24, 1884 began like any other day in the small town of Helena, Texas. Helena was known as the toughest town on earth… and the town was filled with cowboys waiting for the spring cattle drives going north, Civil War veterans, highwaymen and gunmen. In the early 1800’s the Southwest was part of Mexico, and Mexico was under the domination of Spain. Because the Spanish were afraid of the expansion of the Anglos, they closed the area to anyone from the states. Any American trader they found in the area ended up in jail.

In the early 1800’s the Southwest was part of Mexico, and Mexico was under the domination of Spain. Because the Spanish were afraid of the expansion of the Anglos, they closed the area to anyone from the states. Any American trader they found in the area ended up in jail.

Coal was very important for the operation of the railroad. And because of that, many railroads controlled their supply of coal by owning the coal-mining operations. One such mining operation owned by the Union Pacific Railroad was located in Rock Springs, Wyoming.

Coal was very important for the operation of the railroad. And because of that, many railroads controlled their supply of coal by owning the coal-mining operations. One such mining operation owned by the Union Pacific Railroad was located in Rock Springs, Wyoming.

In 1879 his past finally caught up with him, and he was arrested for killing the man back in 1875. At the trial General Miles testified on his behalf. It took the jury just one half hour to bring back a verdict of not guilty.

In 1879 his past finally caught up with him, and he was arrested for killing the man back in 1875. At the trial General Miles testified on his behalf. It took the jury just one half hour to bring back a verdict of not guilty.

Deacon Miller was a little man who was quiet, and never cussed. He dressed like a traveling minister, and was an avid churchgoer. At the same time, this Jekyll-Hyde character was one of the most ruthless assassins of the Old West. It’s estimated that 40 or more people died from lead that came from his guns… Some of them were even his relatives. His contracts were usually carried out on unarmed men from behind a rock or tree, while using a rifle.

Deacon Miller was a little man who was quiet, and never cussed. He dressed like a traveling minister, and was an avid churchgoer. At the same time, this Jekyll-Hyde character was one of the most ruthless assassins of the Old West. It’s estimated that 40 or more people died from lead that came from his guns… Some of them were even his relatives. His contracts were usually carried out on unarmed men from behind a rock or tree, while using a rifle. Deacon Miller’s last contract kill was on a lawman named Gus Babbitt. As was his style, Miller ambushed Babbitt. Unfortunately, Babbitt lived long enough to describe Miller. Miller and his three helpers were arrested.

Deacon Miller’s last contract kill was on a lawman named Gus Babbitt. As was his style, Miller ambushed Babbitt. Unfortunately, Babbitt lived long enough to describe Miller. Miller and his three helpers were arrested.