REVEREND PEABODY

It required a special “Man of God” to minister to wild frontier towns. There were few towns as wild as Tombstone, Arizona…and there were few ministers who were capable of bringing God to a town like Tombstone than Reverend Peabody.

It required a special “Man of God” to minister to wild frontier towns. There were few towns as wild as Tombstone, Arizona…and there were few ministers who were capable of bringing God to a town like Tombstone than Reverend Peabody.

In 1882, Tombstone, Arizona was a wild frontier town. Of every three downtown businesses, two were either saloons or gambling dens. At this time, Tombstone had approximately 4,000 residents. Only a few citizens were interested in attending church. Churches were usually in a tent. And, the sound of the honky-tonk pianos and the nearby saloons would often drown out the minister.

All of this changed on January 28, 1882 when Reverend Endicott Peabody arrived in town. Although Reverend Peabody was an Episcopal Minister educated back east and in England, he wasn’t a typical minister. He weighed around 200 pounds, enjoyed boxing and baseball, and worked out every day. As one contemporary said, “He had muscles of iron.” While not tending to his perish, Peabody umpired baseball games, and refereed boxing matches.

The Episcopal women had been holding raffles for the building fund, and their husbands were working on the church. Progress was slow. Peabody, not one to be easily intimidated, solicited donations on both sides of Tombstone’s “Dead Line.”

He went into a hotel casino; walked up to a high-stakes poker game; introduced himself; and asked for a donation for the church. One player handed over $150 in chips, and told everyone else to do the same. The local musical society put on the opera H.M.S. Pinafore with the proceeds going to the church building fund. It raised $250 because saloons bought a lot of tickets that were never used.

Six months after Reverend Peabody’s arrival, St. Paul’s Episcopal Church was completed. Right after its completion, Peabody went back to Massachusetts. St. Paul’s is still in Tombstone, and is one of Arizona’s oldest Protestant churches.

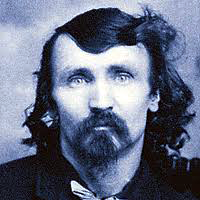

LIVER-EATING JOHNSON

On January 21, 1900 one of the Old West’s most intriguing and gruesome men died in a veterans’ hospital i n California. This was a strange ending for this man who was depicted in a movie Starring Robert Redford called “Jeremiah Johnson”.

n California. This was a strange ending for this man who was depicted in a movie Starring Robert Redford called “Jeremiah Johnson”.

John Johnson was a red bearded giant of a man who headed to the mountains when most mountain men were leaving them.

Early on Johnson came across a covered wagon that had been attached by Indians. The only survivor was the mother…and she had been driven mad from the experience. Over the years John Johnson provided her with food.

The Indians left her alone because they felt she had been driven mad from the touch of the Great Spirit.

Johnson took a Flathead woman as his wife. When he was away trapping, a Crow raiding party killed his wife, and the baby she was carrying.

This started the legend for which “Liver-Eating” Johnson is known. For 20 years Johnson took revenge against the Crow. He supposedly killed as many as 300 Crow Indians, with a few Sioux thrown in for extra measure…And legend says he ate the livers of the Indians he killed.

Later “Liver-Eating” Johnson came out of the mountains, and joined the Union Army during the Civil War. After the war, he was a deputy sheriff in Wyoming.

As he got older, Johnson made peace with the Crow Indians…And on January 21, 1900, he died in a veterans’ hospital in California.

Why did John Johnson eat the livers of the Indians? Was he a cannibal?…Technically, yes…But Indians often ate the raw liver of animals they killed. They believed it would transfer the power of the animal to the hunter. Maybe he wanted the Indians to think anyone who would do something this gruesome was touched by the Great Spirit.

JOHN FREMONT POLITICIAN

After being kicked out of college for “incorrigible negligence,” John C. Fremont became a member of the U. S. Topographical Corp.  The result of a wise marriage to the daughter of an influential Senator, Fremont was appointed to head expeditions charting the best routes to Washington, Oregon, California and Nevada. His reports on the expeditions became very popular with people interested in settling the west.

The result of a wise marriage to the daughter of an influential Senator, Fremont was appointed to head expeditions charting the best routes to Washington, Oregon, California and Nevada. His reports on the expeditions became very popular with people interested in settling the west.

At this time, California was a possession of Mexico. But, the United States was very interested in acquiring it. Although a member of the army, Fremont was not considered a combat soldier. But, in 1845, President James Polk sent Fremont on an expedition with 60-armed men. Although outwardly another exploration, President Polk, feeling war with Mexico was inevitable, wanted a military force nearby.

When in May of 1846 war was declared with Mexico, Fremont immediately went into California. With news of a U. S. military force in California, Anglo-Americans started rebelling against their Mexican leaders. On January 16, 1847 Fremont, now in Los Angeles, was appointed the Governor of California. Although appointed by his commander, there became a dispute within military ranks, and Fremont ended up being court martialed. Even though he was pardoned by President Polk, Fremont resigned, and returned to California.

Still with the taste of political power from his short stint as California’s governor, Fremont ran for senator in the newly recognized state. Then in 1856 Fremont became the Republican Party’s first Presidential candidate. In 1878, as a 65-year-old legend, he was appointed the territorial Governor of Arizona.

John Fremont was a much better explorer and mapper than he was a politician, for his service as a politician was like his time in college, highlighted by “incorrigible negligence.”

FRANK JAMES BORN

It interesting how sometimes a man’s death is almost more important than his life when it comes to fame.

On January 10, 1843, Frank James was born in Clay County, Missouri. Frank was the older brother of Jesse James. Together, the two of them robbed banks, trains and even city fair ticket booths in the middle of a crowd of 10,000 people.

On January 10, 1843, Frank James was born in Clay County, Missouri. Frank was the older brother of Jesse James. Together, the two of them robbed banks, trains and even city fair ticket booths in the middle of a crowd of 10,000 people.

This happened during a time when the citizens of Missouri had a hatred for large corporate railroads and banks. Although they were anything but, some Americans began to see the James brothers as heroes, modern-day Robin Hoods who stole from the rich and gave to the poor.

When Jesse was killed for $5,000 in reward money in 1882 by one of his own gang members, Jesse achieved a reputation as a martyr in the cause of the common people against powerful interests. One Kansas City newspaper mournfully reported his death in a story headlined, “GOODBYE JESSE.”

Frank James, on the other hand, turned himself in a few months after his brother was murdered. Prosecutors were unable to convince juries that Frank was a criminal, and he was declared a free man after avoiding conviction at three separate trials in Missouri and Alabama.

For the next 30 years, Frank lived an honest and peaceful existence, working as a race starter at county fairs, a theater doorman, and a star attraction in traveling theater companies. He also guided people on a tour of his and Jesse’s family farm. Frank died in 1915 at the age of 72.

Today Frank James is known best as Jesse James’ brother. It seems sometimes a person has to leave this world in a spectacular way to receive enduring fame.

ALFRED PACKER

On January 7, 1901 Alfre d Packer was released from prison after serving 18 years. Why was he in prison? Cannibalism.

d Packer was released from prison after serving 18 years. Why was he in prison? Cannibalism.

Back in the 1860’s Packer was a prospector in the Rocky Mountains. Because of the meager pickings, he supplemented his income by serving as a guide in the Utah and Colorado wilderness.

In early November 1873, Packer left Bingham Canyon, Utah, leading a party of 21 men bound for the gold fields near Breckenridge, Colorado. After three months of difficult travel, the party staggered into the camp of the Ute Indian Chief Ouray, near present-day Montrose, Colorado. The Ute graciously provided the hungry and exhausted men with food and shelter. Although the Ute advised the men to stay in the camp until spring, Packer and five other men decided to continue the journey.

Two months later, Packer arrived alone at the Los Pinos Indian Agency, looking surprisingly fit for a man who had just completed an arduous winter trek through the Rockies. At first Packer claimed he had become separated from his five companions during a blizzard and survived on wild game.

Later Packer confessed that four men had died naturally from the extreme winter conditions and the starving survivors ate them. When only Packer and one other man, Shannon Bell, remained alive, Bell went insane and threatened to kill Packer. Packer said he shot Bell in self-defense and eventually ate his corpse.

Packer was tried and a jury convicted him of manslaughter. He remained imprisoned in the Canon City penitentiary until 1901 when the Denver Post published a series of articles and editorials questioning his guilt.

After his release Alfred Packer around Littleton, Colorado, maintaining his innocence until the day he died in 1907.

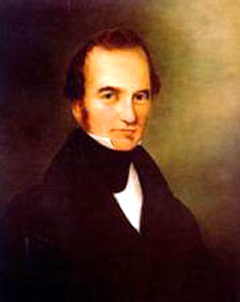

STEPHEN AUSTIN JAILED

On January 2, 1834 Stephen Austin was imprisoned by the Mexican government.

Prior to this Austin did his best to satisfy the rebellious Anglo-Americans in Texas. And because of proble ms with the Mexican Republic, Austin was forces to constantly return to Mexico City where he argued for the rights of the American colonists in Texas.

ms with the Mexican Republic, Austin was forces to constantly return to Mexico City where he argued for the rights of the American colonists in Texas.

Alarmed by the growing numbers of Americans migrating to Texas and rumors the U.S. intended to annex the region, the Mexican government began to limit immigration in 1830.

The Mexican policy angered many Anglo-American colonists who already had a long list of grievances against their distant government. In 1833, a group of colonial leaders drafted a constitution that would create a new Anglo-dominated Mexican state of Texas.

Once the constitution was done, the colonial leaders directed Austin to travel to Mexico City to present it to the government along with a list of other demands. Austin conceded to the will of the people, but President Santa Ana not only refused to grant Texas independence, he threw Austin in prison on suspicion of inciting insurrection.

When he was finally released eight months later in August 1835, Austin found that the Anglo-American colonists were on the brink of rebellion. They were now demanding a Republic of Texas that would break entirely from Mexico.

Reluctantly, Austin abandoned his hope that the Anglo Texans could somehow remain a part of Mexico, and he began to prepare for war. The following year Austin helped lead the Texan rebels to victory over the Mexicans and assisted in the creation of the independent Republic of Texas. Defeated by Sam Houston in a bid for the presidency of the new nation, Austin instead took the position of secretary of state. He died in office later that year.

WOUNDED KNEE

On December 29 in 1890, the final chapter in America’s Indian wars was written as the U.S. Cavalry killed 146 Sioux at Wounded Kne e.

e.

Throughout 1890, the U.S. government had been worrying about a Ghost Dance spiritual movement, which taught that Indians had been defeated and confined to reservations because they had angered the gods by abandoning their traditional customs. If they practiced the Ghost Dance and rejected the ways of the white man, the gods would create the world anew and destroy all non-believers, including non-Indians.

The U.S. Army’s 7th cavalry surrounded a band of Ghost Dancers under the Sioux Chief Big Foot near Wounded Knee Creek and demanded they surrender their weapons. As that was happening, a fight broke out between an Indian and a U.S. soldier and a shot was fired. A brutal battle followed, in which it’s estimated almost 150 Indians were killed. Nearly half of them were women and children. The cavalry lost 25 men.

HARDIN’S CHRISTMAS

Although he’s not as famous as Billy the Kid or Jesse James, John Wesley Hardin probably holds the record for killing more men in the shortest period of time. From the time he first killed in 1868 until he shot his last man ten years later, Hardin is known to have murdered more than 20 men. Incidentally, his father was a Methodist preacher, and he was named after the founder of the Methodist Church.

Although he’s not as famous as Billy the Kid or Jesse James, John Wesley Hardin probably holds the record for killing more men in the shortest period of time. From the time he first killed in 1868 until he shot his last man ten years later, Hardin is known to have murdered more than 20 men. Incidentally, his father was a Methodist preacher, and he was named after the founder of the Methodist Church.

So, how did John Wesley Harden spend Christmas of 1869? On Christmas Day he went to the tiny town of Towash, Texas, seeking some holiday companionship and a good game of cards. A big winner, Hardin got in an argument with a man named James Bradley, an obvious sour looser.

Bradley pulled a knife. Unarmed, in accordance with town ordinances, Harden went to his room and got his pistol. Later in the afternoon Harden encountered Bradley on the street. Bradley let out some curse words; pulled his pistol; and shot at Harden…Missing him. Hardin responded with a shot to Bradley’s head and chest. Harden then casually rode out of town.

The moral of the story? Christmas should be spent in church, with family, not gambling and shooting off your gun. Right, James Bradley?

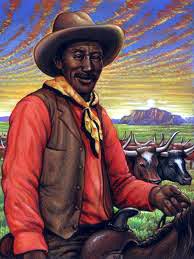

BILL PICKETT

I’m sure everyo ne who visits Cowboy To Cowboy is a fan of the rodeo.

ne who visits Cowboy To Cowboy is a fan of the rodeo.

One of the more fun events is steer wrestling. Have you ever wondered how it got its start? Well, wonder no more. Here’s the story

The son of black and Indian parents, Bill Pickett…who was born on December 5, 1871…learned his roping and riding skills while working as a cowboy on a Texas ranch..

Later he went to work for the 101 Ranch Rodeo. As a special attraction for the audiences, Pickett would ride his horse alongside a running longhorn steer. Then he would grab the steer’s head and bit its upper lip—an effective means of forcing the steer to follow Pickett’s commands.

Since bulldogs were known to control cattle by biting onto their lower lips and ferociously hanging on, Pickett’s steer wrestling method became known as “bulldogging.”

It’s unlikely that any working cowboy ever attempted to control a steer by “bulldogging” it, but the audience loved Pickett’s stunt. Although few cowboys were willing to copy Pickett’s lip-biting method, steer wrestling became a standard rodeo competition.

Pickett’s bulldogging performance made him a national rodeo star. The 101 Ranch closed in 1931, and Pickett died a forgotten man not long afterwards, at age 70, from injuries suffered while working horses for the 101 Ranch in Texas.

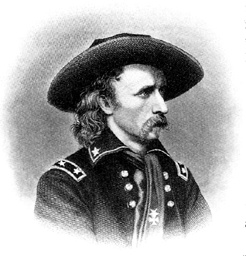

CUSTER & BLACK KETTLE

It was November 27, 1868 when Lieutenant Colonel (Who, incidentally, was no longer a General) attacked a band of peaceful Cheyenne living with Chief Black Kettle.

Earlier in 1868 Custer was convicted of desertion and mistreatment of soldiers by a military court, the government had suspended Custer from rank and command for one year. In September 1868, General Philip Sheridan had reinstated Custer to lead a campaign against Cheyenne Indians who were making raids in Kansas and Oklahoma.

On November 26, Custer located a large village of Cheyenne encamped near the Washita River, just outside of present-day Cheyenne, Oklahoma. Custer did not attempt to identify which group of Cheyenne was in the village, or to make a reconnaissance of the camp.

Had he done so, Custer would have discovered they were peaceful people and the village was on an Indian Reservation, where the commander of Fort Cobb had guaranteed them safety. There was even a white flag flying from one of the main dwellings, indicating the tribe was actively avoiding conflict.

Having surrounded the village the night before, at dawn Custer called for the regimental band to play “Garry Owen,” which signaled for four columns of soldiers to charge into the sleeping village. Outnumbered and caught unaware, scores of Cheyenne were killed in the first 15 minutes. Within a few hours, the village was destroyed. A total of 103 Cheyenne, including the peaceful Black Kettle and many women and children were killed.

Although anything but, it was hailed as the first substantial American victory in the Indian wars. However, it helped restore Custer’s reputation and succeeded in persuading many Cheyenne to move to the reservation.

Incidentally, Custer’s habit of boldly charging Indian encampments of unknown strength would eventually catch up with him at the Battle of the Little Bighorn.

POWDER RIVER BATTLE

Just five months after the Little Bighorn Battle, on November 25, 1876, in retaliation, U.S. troops under the leadership of General Ranald Mackenzie destroyed the village of Cheyenne living with Chief Dull Knife on the Powder River.

Just five months after the Little Bighorn Battle, on November 25, 1876, in retaliation, U.S. troops under the leadership of General Ranald Mackenzie destroyed the village of Cheyenne living with Chief Dull Knife on the Powder River.

Although the Sioux and Cheyenne had won one of their greatest victories at Little Bighorn, this victory actually marked the beginning of the end of their fight against the U.S. government.

News of the massacre of Custer and his men reached the East Coast during the centennial celebrations on July 4, 1876. This outraged the citizens and Americans demanded retaliation.

The government responded by sending one of its most successful Indian fighters to the region, General Ranald Mackenzie, who had previously defeated the Comanche and Kiowa Indians in Texas. Mackenzie led an expeditionary force up the Powder River in central Wyoming, where he located a village of Cheyenne living with Chief Dull Knife. Although Dull Knife himself probably wasn’t involved in the battle at Little Bighorn, many of his people were, including one of his sons.

At dawn, Mackenzie and over 1,000 soldiers and 400 Indian scouts opened fire on the sleeping village, killing many Indians within the first few minutes. Some of the Cheyenne were able to escape to the surrounding hills. The Indians watched as the soldiers burned more than 200 lodges that contained all their winter food and clothing. Then the soldiers cut the throats of their ponies. When the soldiers found souvenirs taken by the Cheyenne from soldiers they had killed at Little Bighorn, the assailants felt justified in their attack.

The surviving Cheyenne, many of them half-naked, began an 11-day walk north to Crazy Horse’s camp. Devastated by his losses, the next spring Dull Knife convinced the remaining Cheyenne to surrender. The army sent them south to Indian Territory, where other defeated survivors of the final years of the Plains Indian wars soon joined them.

It makes one wonder how things would have been different had the Little Bighorn not taken place.

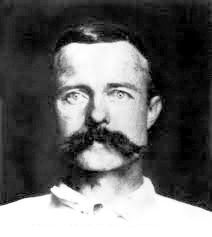

TOM HORN

On November 21, 1860 hired killer Tom Horn was born in Memphis, Missouri. Tom was raised on a farm, and like many young farm boys, he loved to roam the woods with his dog and rifle, hunting for game. He was an unusually skilled rifleman, an ability that may have later encouraged him to gravitate towards a career as a professional killer.

On November 21, 1860 hired killer Tom Horn was born in Memphis, Missouri. Tom was raised on a farm, and like many young farm boys, he loved to roam the woods with his dog and rifle, hunting for game. He was an unusually skilled rifleman, an ability that may have later encouraged him to gravitate towards a career as a professional killer.

At the age of 14, Tom left home after a particularly savage beating from his father. He started working as a teamster with mules in Santa Fe, New Mexico. His skills got him a job with the U.S. Army, where he served as an interpreter with the Apache Indians; learned to be a skilled scout and tracker; and tracked the cunning movements of the famous Apache warrior Geronimo.

Tom started his career as a hired gunman when he went to work for the Pinkerton Detective Agency. Horn’s four-year stint with the Pinkertons impressed his next employer, the Wyoming Swan Land and Cattle Company. Swan and other big ranches hired Tom to control rustlers. It’s not known exactly how many rustlers and other troublemakers he killed.

“Killing is my specialty,” Horn reportedly once said. “I look at it as a business proposition, and I think I have a corner on the market.”

In 1903, Tom Horn was arrested and hanged for the killing of a 14-year-old boy.

Many historians today don’t believe Tom killed the boy. Although it carried no legal weight, few years ago Tom was given another trial, and found innocent.

TIME ZONES

At exactly noon on November 18, 1883, American and Canadian railroads begin using four continental time zones to end the confusion of de aling with thousands of local times. It shows just how powerful the railroads were.

aling with thousands of local times. It shows just how powerful the railroads were.

The need for the time zones resulted from the problems the railroads had in moving passengers and freight over the thousands of miles of rail line that covered North America in the 1880s. Back then most of the towns set their clocks to the local movement of the sun. It was based on “high noon,” or the time when the sun was at its highest point in the sky.

Back when it was days between towns, the time differences didn’t matter. But as railroads shrink the travel time between cities to hours, these local times became a scheduling nightmare. Railroad timetables in major cities listed dozens of different arrival and departure times for the same train, each linked to a different local time zone.

Rather than turning to the federal governments of the United States and Canada, the railroads created a new time code system themselves. The companies divided the continent into four time zones…very close to the ones we still use today.

Most Americans and Canadians quickly embraced these new time zones, since railroads were their main link with the rest of the world. However, it was not until 1918 that Congress officially adopted the railroad time zones and put them under the supervision of the Interstate Commerce Commission.

BUCKSKIN & THE KID HAVE IT OUT

Although Tombstone, Arizona is known for the OK Corral Shootout, on November 14, 1882 another shootout took place between two Old West characters with unique nicknames. The shootout was between gunslinger Franklin “Buckskin” Leslie and Billy “The Kid” Claiborne.

Although Tombstone, Arizona is known for the OK Corral Shootout, on November 14, 1882 another shootout took place between two Old West characters with unique nicknames. The shootout was between gunslinger Franklin “Buckskin” Leslie and Billy “The Kid” Claiborne.

Tombstone was the home to many gunmen who never achieved the fame of Wyatt Earp or Doc Holliday. Probably one of the most notorious of these forgotten outlaws was “Buckskin” Frank Leslie.

Little is know of his early life. At different times, he claimed to have been born in both Texas and Kentucky. Although there is no supporting evidence, he also said he studied medicine in Europe, and had been an army scout in the war against the Apache Indians.

Drawn by the moneymaking opportunities of the booming mining town of Tombstone, he opened the Cosmopolitan Hotel in 1880. That same year he killed a man named Mike Killeen during a quarrel over Killeen’s wife, and he married the woman shortly thereafter.

When John Ringo was found dead in July 1882, a young friend of Ringo’s named Billy “The Kid” Claiborne, was convinced that Leslie had murdered Ringo. A cocky young man who took on the nickname “The Kid” after Billy The Kid, seeking vengeance and the notoriety that would come from shooting a famous gunslinger, unwisely decided to publicly challenge Leslie, who shot him dead without hesitation.

BLACK BART

On November 3, 1883, the law almost caught California’s most infamous stagecoach robber called Black Bart. Although he managed to make a getaway, he dropped evidence that eventually sent him to priso n.

n.

Black Bart was born Charles E. Boles around 1830. He abandoned his family for the gold fields of California. When he failed to strike it rich as a miner, he turned to a life of crime.

By the mid-1850s, Well Fargo stagecoaches in Northern California transported not only passengers, but money as well. Because they traveled isolated areas, the stagecoaches became favorite targets for bandits.

It’s believed Boles committed his first stagecoach robbery in July 1875. Wearing a flour sack over his head with holes cut for his eyes, he intercepted a stage near the California mining city of Copperopolis. When guards spotted gun barrels sticking out of nearby bushes, they handed over their strong box. He escaped on foot with the gold, though his “gang” of camouflaged gunmen stayed behind. When the guards returned to pick up the box, they discovered that the “rifle barrels” were just sticks tied to branches.

Known as Black Bart…the name of a western novel character…Boles embarked on a series of stagecoach robberies. He never shot anyone nor robbed a single stage passenger…his shotgun wasn’t even loaded. He gained fame for his daring style and the occasional short poems he left behind, signed by “Black Bart, the Po-8.”

During the robbery that took place on this date Boles was wounded and left behind a handkerchief with a laundry mark. A Wells Fargo detective searched the San Francisco laundries until they found the laundry that led to Boles. The detective found he was a dignified elderly man that everyone though was a mining engineer.

Arrested and tried, Boles pleaded guilty and received a sentence of six years in San Quentin prison. The “Po-8” bandit stole only about $18,000 during the eight years of his criminal career.

There are stories that say when Boles got out of jail Wells Fargo agreed to pay him $200 a month not to rob any more of their stages.

BILL TILGHMAN

On November 1, 1924 one of the last Old West lawman died. Bill Tilghman was 71 years old and still serving as a lawman at the time.

Coming out west  at the age of 16, he fell in with a group of less than honest young men who stole horses from Indians. After several narrow escapes with angry Indians, Tilghman decided rustling was too risky and went to Dodge City, Kansas, where he served a short while as a deputy marshal before opening a saloon. Incidentally, he was arrested twice for train robbery and rustling, but the charges didn’t stick.

at the age of 16, he fell in with a group of less than honest young men who stole horses from Indians. After several narrow escapes with angry Indians, Tilghman decided rustling was too risky and went to Dodge City, Kansas, where he served a short while as a deputy marshal before opening a saloon. Incidentally, he was arrested twice for train robbery and rustling, but the charges didn’t stick.

In spite of this shaky start, Tilghman built a reputation as an honest young man in Dodge City. He became the deputy sheriff of Ford County, Kansas, and later, the marshal of Dodge City. In 1891 Tilghman became a deputy U.S. marshal for the Oklahoma Territory. Lawlessness plagued Oklahoma, and Tilghman helped restore order by capturing some of the most notorious bandits of the day.

Over the years, Tilghman earned a well-deserved reputation for treating even the worst criminals fairly and protecting the rights of the unjustly accused. Any man in Tilghman’s custody knew he was safe from angry vigilante mobs, because Tilghman had little tolerance for those who took the law into their own hands.

In 1924, after serving a term as an Oklahoma state legislator; making a movie about his frontier days; and serving as the police chief of Oklahoma City, Tilghman accepted a job as city marshal in Cromwell, Oklahoma.

How did he die? Not of old age or at the hands of a hardened outlaw. Tilghman was shot and killed while trying to arrest a drunken Prohibition agent.

BARBED WIRE

Probably no other one invention changed the face of the west and the life of the cowboy more than the one applied for on October 27, 1873

Probably no other one invention changed the face of the west and the life of the cowboy more than the one applied for on October 27, 1873

A De Kalb, Illinois farmer named Joseph Glidden submitted an application to the U.S. Patent Office for his design for a fencing wire with sharp barbs.

Glidden came up with his design after seeing an exhibit of single-stranded barbed wire at the De Kalb county fair. But Glidden’s design improved on this wire by using two strands of wire twisted together to hold barbed spur wires firmly in place…Incidentally, Glidden used his wife’s coffee grinder to twist that first wire.

Glidden’s wire was also well suited to mass production techniques, and by 1880 more than 80 million pounds of inexpensive Glidden-style barbed wire was sold, making it the most popular wire in the nation. Plains farmers quickly discovered that Glidden’s wire was the cheapest, strongest, and most durable way to fence their property. As one person wrote, “it takes no room, exhausts no soil, shades no vegetation, is proof against high winds, makes no snowdrifts, and is both durable and cheap.”

The effect of this simple invention on the life in West was great. Since the plains were largely treeless, a farmer who wanted to construct a fence had little choice but to buy expensive and bulky wooden rails shipped by train and wagon from distant forests. Without barbed wire, few farmers would have attempted to homestead on the Great Plains, because they wouldn’t be able to protect their farms from grazing herds of cattle and sheep.

Barbed wire also brought an end to the era of the open-range cattle industry. Within a few years, many ranchers discovered that homesteaders were fencing the open range where their cattle had once freely roamed, and that the old technique of driving cattle over miles of unfenced land to railheads in Dodge City or Abilene was no longer possible. In addition, the ranchers fenced in their cattle, changing the cowboy’s job to riding and repairing fences.

TRANSCONTINENTAL TELEGRAPH

On October 24, 1861, the Western Union Telegraph Company linked the nation’s eastern and western telegraph networks at Salt Lake  City, Utah, completing a transcontinental line that allowed instantaneous communication between Washington, DC and San Francisco, California. The first official telegraph was sent by California Chief Justice Stephen J. Field to President Abraham Lincoln, predicting that the telegraph would ensure the loyalty of the western states to the Union during the Civil War.

City, Utah, completing a transcontinental line that allowed instantaneous communication between Washington, DC and San Francisco, California. The first official telegraph was sent by California Chief Justice Stephen J. Field to President Abraham Lincoln, predicting that the telegraph would ensure the loyalty of the western states to the Union during the Civil War.

The push to create a transcontinental telegraph line had begun only a little more than year before when Congress authorized a subsidy of $40,000 a year to any company building a telegraph line that would join the eastern and western networks. The Western Union Telegraph Company took up the challenge, and immediately began work on the section between the western edge of Missouri and Salt Lake City.

To accomplish this, telegraph wire and glass insulators had to be shipped by sea to San Francisco and carried eastward by horse-drawn wagons over the Sierra Nevada Mountains. Because much of the area was treeless, thousands of telegraph poles had to be shipped from the western mountains.

Indians were also a problem. In the summer of 1861, a party of Sioux warriors took a section of wire for making bracelets. Later some of the Sioux wearing the telegraph-wire bracelets became sick and a Sioux medicine man convinced them that the great spirit of the “talking wire” had avenged its desecration. So, the Sioux left the line alone, and the Western Union was able to connect the East and West Coasts of the nation much earlier than anyone had expected.

Incidentally, the transcontinental telegraph caused the end of the Pony Express.

SUTRO TUNNEL

On October 19, 1869, Prussian-born mining engineer, Adolph Sutro, began work on one of the most ambitious projects of the day: a four-mile-long tunnel through the solid rock at the Comstock Lode mining area.

On October 19, 1869, Prussian-born mining engineer, Adolph Sutro, began work on one of the most ambitious projects of the day: a four-mile-long tunnel through the solid rock at the Comstock Lode mining area.

One of the richest silver deposits in the world, the Comstock Lode was discovered in 1859. But as miners sank shafts deeper into the rock, they began to encounter large amounts of water that had to be pumped to the surface at great expense.

Adolph Sutro’s idea was to tunnel through the rock of the neighboring Mt. Davidson and straight into the heart of the Comstock mine. Mine water would thus drain through the tunnel without need for expensive pumps, and the mining companies would also be able to use the tunnel to move men and ore in and out of the mine, greatly reducing transportation costs.

Although everyone agreed that Sutro’s tunnel would be a boon to the Comstock, progress slowed down by resistance from some of the major mining interests who feared that Sutro would use his tunnel to take control of the entire lode. Only after securing European capital was Sutro able to complete the $5-million project in 1878.

It was every bit as successful as Sutro though it would be. Unfortunately, by 1878, the richer sections of the Comstock Lode had been tapped out. However, Sutro was able to sell the tunnel at a fantastic profit. He moved to San Francisco where he became one of the city’s largest landowners as well as the city’s mayor from 1894 to 1896.

WILD BILL LONGLEY

William Preston Longley was born on October 16, 1815. We don’t know his as William Preston, but as “Wild Bill”, a sadistic and murde rous Old West gunman.

rous Old West gunman.

Although little is know about him as a young man, it’s generally accepted that before he was 20 years old, Longley had already killed several men. He was short-tempered and he frequently killed simply because he believed he had somehow been slighted or insulted. He had a particularly strong dislike of blacks.

Legend has it that Longley was once hanged along with a horse thief; but shots fired back by the departing posse cut his rope, and he was saved.

After killing a minister, Wild Bill fled Texas. But he was captured and returned to Lee County, Texas, where he was tried and found guilty of murder. Sentenced to hang, during his final days Longley became a Catholic, wrote long letters about his life, and claimed that he had actually only killed eight men. On the day of his execution, October 28, 1878, he climbed the steps to the gallows with a cigar in his mouth and told the gathered crowd that his punishment was just and God had forgiven him.

A noose was put around his neck, and he was hanged. Unfortunately, the rope slipped so that Longley’s knees hit the ground. After the hangman pulled the rope taut once more, Wild Bill slowly choked to death. It took 11 minutes before he was pronounced dead.

TOM MIX

On October 11, 1 940, the famous cowboy actor Tom Mix is killed in a freak car accident near his ranch in Florence, Arizona. He was driving his single-seat roadster with luggage on the rear shelf of the car. Tom was traveling along a straight desert road, when he unknowingly came to a bridge spanning a shallow gully that was out. When his car went down into the gully a heavy suitcase flew off the rear shelf of his car and crushed him.

940, the famous cowboy actor Tom Mix is killed in a freak car accident near his ranch in Florence, Arizona. He was driving his single-seat roadster with luggage on the rear shelf of the car. Tom was traveling along a straight desert road, when he unknowingly came to a bridge spanning a shallow gully that was out. When his car went down into the gully a heavy suitcase flew off the rear shelf of his car and crushed him.

Tom Mix had been one of the biggest silent movies stars in Hollywood during the 1920’s, appearing in more than 300 westerns and making as much as $10,000 a week. Unlike most of the actors appearing in westerns, Mix had actually worked as a cowboy, and had been a Texas Ranger.

In 1906, Mix joined a Wild West show, and four years later he started acting in motion pictures. He helped define the classic image of the western movie cowboy as a rough riding, quick-shooting defender of right and justice, an image that would be copied by hundreds of other actors who followed him.

With the coming of talking pictures, Mix’s movie career stalled. When he died in 1940 at the age of 60, he had lost most of his wealth and was largely forgotten.

Today a black iron silhouette of a riderless bronco marks the site of Mix’s death on the highway about 17 miles south of Florence, Arizona.

DALTONS & COFFEYVILLE

On October 5, 1892, the famous Dalton Gang attempted a daring daylight robbery of two Coffeyville, Kansas banks at the same time. The y wanted to do something no other outlaw gang had done. Instead, they were nearly all killed by quick-acting townspeople.

y wanted to do something no other outlaw gang had done. Instead, they were nearly all killed by quick-acting townspeople.

The gang rode into Coffeyville and tied their horses to a fence in an alley near the two banks and split up. Bob and Emmett Dalton headed for the First National, while Grat Dalton led Dick Broadwell and Bill Powers into the Condon Bank.

Unfortunately for the Daltons, they were recognized and the word quietly spread that the town banks were being robbed. The townspeople ran for their guns and surrounded the two banks. When the Dalton brothers walked out of the bank, a hail of bullets forced them back into the building. Regrouping, they tried to flee out the back door of the bank, but the townspeople were waiting for them there as well.

Meanwhile, in the Condon Bank a cashier had managed to delay Grat Dalton, Powers, and Broadwell with the claim that the vault was on a time lock and couldn’t be opened. That gave the townspeople enough time, and suddenly a bullet smashed through the bank window and hit Broadwell in the arm. The three men bolted out the door and fled down a back alley. But they were immediately shot and killed, this time by a local livery stable owner and a barber.

When the gun battle was over, the people of Coffeyville had destroyed the Dalton Gang, killing every member except for Emmett Dalton. But their victory was not without a price…The Dalton’s killed four of the townspeople.

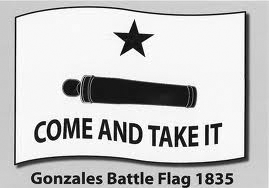

BATTLE OF GONZALES

The ever patient Texans could take no more when on October 2, 1835 Mexican soldiers attempted to disarm the people of Gonzales.

The ever patient Texans could take no more when on October 2, 1835 Mexican soldiers attempted to disarm the people of Gonzales.

Even though Texas had technically been a part of the Spanish empire since the 17th century, as late as the 1820s, there were only about 3,000 Spanish-Mexican settlers in Texas.

After winning its own independence from Spain in 1821, Mexico invited Anglo-Americans to come to Texas in the hopes they would be able to tame the Comanche Indians and the harsh land. During the next decade men like Stephen Austin brought more than 25,000 people to Texas, most of them Americans.

Even though these emigrants became Mexican citizens, they continued to speak English, and had closer trading ties to the United States than to Mexico.

In 1835, the president of Mexico, Antonio Lopez de Santa Anna, overthrew the constitution and appointed himself dictator. Recognizing that the “American” Texans were likely to use his rise to power as an excuse to secede, Santa Anna ordered the Mexican military to begin disarming the Texans whenever possible. This proved more difficult than expected, and on October 2, 1835, Mexican soldiers attempting to take a small cannon from the village of Gonzales encountered stiff resistance from a hastily assembled militia of Texans. After a brief fight, the Mexicans retreated and the Texans kept their cannon.

The determined Texans would continue to battle Santa Ana and his army for another year and a half before winning their independence and establishing the Republic of Texas.

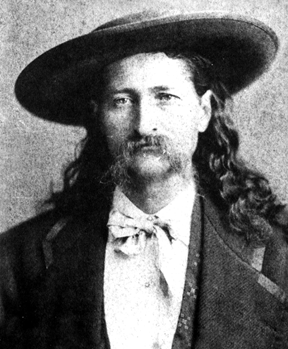

SHERIFF BILL HICKOK

On September 27 back in 1869, Ellis County Sheriff Wild Bill Hickok and his deputy responded to a disturbance by a  local ruffian named Samuel Strawhun and several of his drunken buddies at John Bitter’s Beer Saloon in Hays City, Kansas. Hickok ordered the men to stop, Strawhun turned to attack him, and Hickok shot and killed him.

local ruffian named Samuel Strawhun and several of his drunken buddies at John Bitter’s Beer Saloon in Hays City, Kansas. Hickok ordered the men to stop, Strawhun turned to attack him, and Hickok shot and killed him.

This was typical of Wild Bill’s approach to a confrontation. As one cowboy said, Hickok would stand “with his back to the wall, looking at everything and everybody under his eyebrows–just like a mad old bull.”

But some Hays City citizens wondered if their new cure wasn’t worse than the disease. Shortly after becoming sheriff, Hickok shot a soldier who resisted arrest, and the man died the next day. Then, a few weeks later Hickok killed Strawhun. Even though his ways were effective, many Hays City citizens were less than impressed in that after only five weeks in office he had killed two men.

During the regular November election later that year, the people expressed their displeasure, and Hickok lost to his deputy, 144-89. Though Wild Bill Hickok would later go on to hold other law enforcement positions in the West, his first attempt at being a sheriff had lasted only three months.