Texas Joins The United States

George Armstrong Custer seemed to always live on the edge. Even while at West Point, where, incidentally, he graduated at the bottom of his class, Custer was almost expelled because of demerits for actions like food fights in the cafeteria.

George Armstrong Custer seemed to always live on the edge. Even while at West Point, where, incidentally, he graduated at the bottom of his class, Custer was almost expelled because of demerits for actions like food fights in the cafeteria.

However, one of the low points in his career took place on November 25, 1867 when he was court-martialed. Supposedly, Custer’s officers fell into two categories…those who were related to him, and those who hated him. As for the enlisted men, they fell into one category…those who feared him.

Custer was found guilty on eight counts. They included being absent without leave from his command. He had left his post to visit his wife, Libby. He had also taken along troopers as escort during this trip. Another count was shooting deserters without trial. Incidentally, when Custer left to visit his wife, he was considered a deserter himself.

Libby Custer

The testimony of Captain Frederick Benteen, an officer with Custer at Little Big Horn, was particularly damning. Other charges included abandoning two men, failing to recover two bodies, and cruelty to three wounded troopers. The average officer being found guilty on any of these counts would have meant the end of his career. But George Custer wasn’t average. His sentence was, “to be suspended from rank and command for one year, and to forfeit his pay proper for the same time.”

At the end of the year Custer’s friend and advocate, General Phil Sheridan, called him back to active duty. Custer felt he had to do something spectacular to redeem himself. And he did on November 27, 1868, when Custer and 800 men attacked the peaceful camp of Black Kettle that was flying the American Flag and a white truce flag.

Students of Texas history are familiar with the story of Cynthia Ann Parker, the nine-year-old white girl taken captive by Comanches, May 19, 1836. For the next 24 years, Cynthia Ann lived with her Comanche captors, bore at least four children and somehow survived the rigors of life among the Indians until her rescue in 1860 by a troop of Texas Rangers in a fight known as “The Battle of Pease River.”

By now Cynthia Ann had been assimilated into the tribe, had forgotten most if not all of the English language, resisted parting with her Comanche children, and had become a hardened, sun-burned woman with huge work-worn hands, chopped hair and haunted eyes.

Ripped from her family at age 9, having witnessed the brutal murders of her parents and friends, faced with abuse and humiliation in a Comanche camp, Cynthia Ann Parker became the most famous of the white captives in Texas. There were many hundreds of other white girls and women taken captive by marauding Comanches, too. Most were raped, tortured and killed. Others traded back to their families were covered with scars and facial mutilation. But what made Cynthia Ann different is that one of her children grew up to become Quanah Parker, famous in his own right as a chief and important negotiator between Indians and Whites.

After her rescue, Cynthia Ann never did adjust completely to return to White society. She died of a broken heart in 1870 and is buried at Fort Sill, Oklahoma between two of her Comanche children.

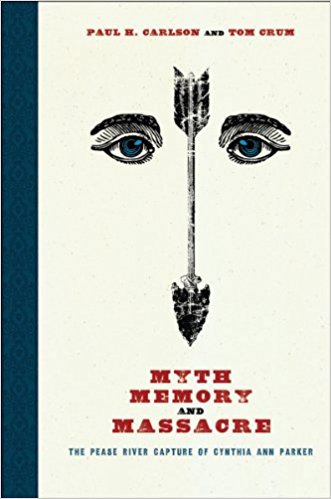

If you are interested in the complete history of the life and times of Cynthia Ann Parker, you must look elsewhere because there are many books available on the subject. This book, Myth, Memory and Massacre delves mainly into events regarding the accidental rescue of Cynthia Ann by the Rangers at Pease River. When the Rangers attacked a Comanche hunting party, they had no idea Cynthia Ann Parker was living with this clan. The Rangers nearly killed her as she ran away clutching her baby, but one of the men realized she had blue eyes and correctly guessed she was a White captive. It took a while to figure out who she was.

From here the authors begin their discussion of who, why, where and how. They carefully dissect events beginning with the initial raid upon the camp, pointing out this was a hunting camp filled with women and children who had been butchering and preparing buffalo meat for winter. Most of the Indians killed were women and children. The surprise rescue of the white woman is what caused such a sensation throughout Texas since nobody thought Cynthia Ann could still be alive. The publicity gave some individuals riding with the Rangers the opportunity for self importance and political gain. Their actions, motives and self-promotion are exposed with regard to their showing the battle of Pease River had been a great victory with many more Indians killed, and at least one war chief taken out of action, which was probably not true.

The authors have done a great deal of careful research and tedious fact- finding. Their conclusions are meant to clear up, in their opinion, many falsehoods regarding the rescue of Cynthia Ann that after many years of telling and re-telling has become folklore. The authors aim to show how the rescue of Cynthia Ann Parker was eventually used for political advantage, and finally how the analyzation of these events historically have been misleading. For those interested in “the rest of the story” concerning Cynthia Ann Parker, this book might help close the final chapter. You can tell for yourself and grab this amazing book HERE.

Editor’s Note: The reviewer, Phyllis Morreale-de la Garza is the author of numerous books about the Old West including Hell Horse Winter of the Apache Kid, Silk Label Books, P.O. Box 700, Unionville, New York 10988 vvww.silklapelbooks.

*Courtesy of Chronicle of the Old West newspaper, for more click HERE.

A while back Dakota was a guest on Haunted Saloon TV, where he was interview at the OK Corral shoot out site by Terry “Ike” Clanton. Clanton is a fourth generation cousin of the legendary Joseph “Ike” Clanton of OK Corral gunfight fame.

When Jacob Waltz died on October 25, 1891, he became either the world’s greatest prankster or the world’s greatest secret keeper. Although during his life his last name was spelled a number of different ways, we simply know him as “The Dutchman”… the man who discovered the “Lost Dutchman’s Mine” in the Superstition Mountains, just outside of Phoenix, Arizona.

When Jacob Waltz died on October 25, 1891, he became either the world’s greatest prankster or the world’s greatest secret keeper. Although during his life his last name was spelled a number of different ways, we simply know him as “The Dutchman”… the man who discovered the “Lost Dutchman’s Mine” in the Superstition Mountains, just outside of Phoenix, Arizona.