The Gray Fox; George Crook and the Indian Wars, Paul Magid, University of Oklahoma Press, (800 627-7377), $29.95, Cloth, 480 pages, Photographs, Notes, Bibliography, Index.

The Gray Fox; George Crook and the Indian Wars, Paul Magid, University of Oklahoma Press, (800 627-7377), $29.95, Cloth, 480 pages, Photographs, Notes, Bibliography, Index.

This book is the second of a trilogy written about the life and military career of General George Crook. The author concentrates here on the years 1866-1877. (The first book is titled From the Redwoods to Appomattox, telling about Crook’s early life and including his involvement in the Civil War, check it out HERE).

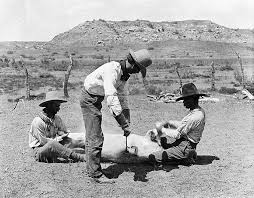

Born in Ohio in 1829, raised on the family farm, Crook was admitted to West Point when he was eighteen years old. He graduated near the bottom of his class in 1852. The Indians nicknamed him “The Gray Fox,” which was not exactly a compliment. Crook stood close to six feet tall, with blue eyes a little too close together, a sharply pointed nose, graying close-clipped hair, thin lips and humorless personality. He served for eight years on the Pacific Coast where he campaigned against Indians in both the Rogue River War and the Yakima War. When necessary, he could live off the land. His hunting expeditions while in the field became one of his peculiarities. Crook rarely dressed in military garb while campaigning. He was usually found wearing canvas clothing, high work boots and a straw hat. In Arizona he rode a mule named Apache. Crook relied heavily on mule packing opposed to hauling supplies and equipment in slow-moving wagon trains.

Author Magid follows the tortured and twisting trails of General Crook throughout the early Apache campaign in Arizona, and then Crook is transferred to the Northwest where he is embroiled in battles against Sioux and Cheyenne warriors. Readers follow him through long, grueling marches, freezing winter snows, forage shortages, sick and starving horses, loss of life and always the political harangues he faced with his superiors in Washington, D.C.

Crook was notorious for keeping battle plans to himself, much to the annoyance of some officers in his command. He was known to go off by himself to hunt game, returning to camp with fish and fowl, and occasionally deer or buffalo meat for the troops. He eventually learned the art of taxidermy to preserve some of. his best trophies. He was eccentric, somewhat mysterious, tough on himself as well as the men around him, but the Indians considered him a worthy and dangerous foe. They knew he was a man of his word.

This book is hardly a long, dry history lesson. The talented author keeps the story rolling forward with easy-to-read prose. Crook’s personality is fairly dealt with, even though the man was difficult to understand. Crook had a myriad of complicated issues to deal with, but kept his stoic silence most of the time. The author obviously is a Crook fan, and is to be commended for writing about the murder of Crazy Horse as honestly as possible, telling all sides of the story. Most likely Crook was aware of the skullduggery afoot. When, at the end of the Sioux War, Crazy Horse was lured to Camp Robinson on the pretext of talks about a reservation for his people, the war chief was captured instead, and brutally murdered inside the fort.

When we turn the last page, we have mixed emotions about General Crook. He left no personal diaries or notes about himself, so history must rely on the observations of those who worked and lived with him, as well as his military successes and failures. Criticized by some, praised by others, General Crook is a fascinating personality.

We look forward to the third book in Magid’s trilogy focusing on Crook’s involvement ending the Apache Wars in Arizona.

Editor’s Note: Reviewer Phyllis Morreale-de la Garza is the author of numerous books about the Old West, including the novel Hell Horse Winter of the Apache Kid, published by Silk Label Books, P.O. Box 700, Unionville, New York 10988-0700, www.silklabelbooks.corn.

*Courtesy of Chronicle of the Old West newspaper, for more click HERE.

In the late 1860’s and the 1870’s a cattle rancher’s life was simple. He lived in a small cabin, and worked along side the cowboys on his ranch. A cowboy respected his boss, and he would give his life for the rancher and his cattle. As they phrased it, “They rode for the brand.” No one would have thought that cowboys go on strike.

In the late 1860’s and the 1870’s a cattle rancher’s life was simple. He lived in a small cabin, and worked along side the cowboys on his ranch. A cowboy respected his boss, and he would give his life for the rancher and his cattle. As they phrased it, “They rode for the brand.” No one would have thought that cowboys go on strike.

In the 1860’s when a pioneer family headed out west, they usually did it in a covered wagon pulled by horses or oxen. One man, Samuel Peppard, didn’t have horses or oxen, but that didn’t stop him. His idea was a Wind Wagon.

In the 1860’s when a pioneer family headed out west, they usually did it in a covered wagon pulled by horses or oxen. One man, Samuel Peppard, didn’t have horses or oxen, but that didn’t stop him. His idea was a Wind Wagon. Chronicle of the Old West is a 20-page newspaper that contains articles from actual 1800s publications and currently written articles written as if the event has just happened. You would swear it was found in your great grandfather’s old trunk. For more info click

Chronicle of the Old West is a 20-page newspaper that contains articles from actual 1800s publications and currently written articles written as if the event has just happened. You would swear it was found in your great grandfather’s old trunk. For more info click  The Gray Fox; George Crook and the Indian Wars, Paul Magid, University of Oklahoma Press, (800 627-7377), $29.95, Cloth, 480 pages, Photographs, Notes, Bibliography, Index.

The Gray Fox; George Crook and the Indian Wars, Paul Magid, University of Oklahoma Press, (800 627-7377), $29.95, Cloth, 480 pages, Photographs, Notes, Bibliography, Index.